[Spring-Summer 2014]

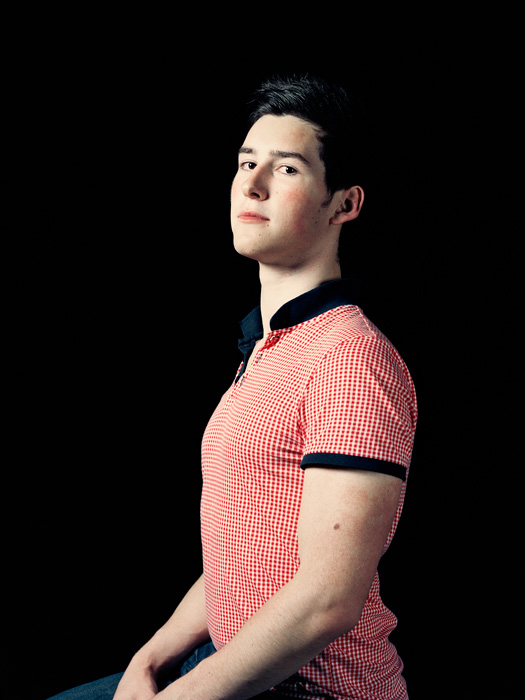

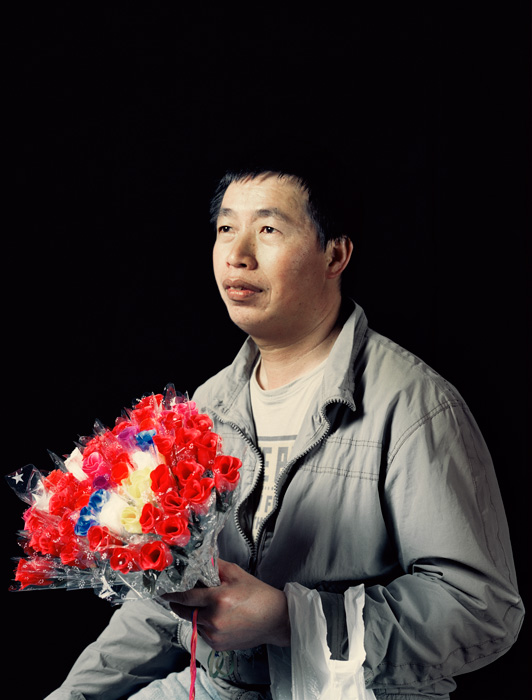

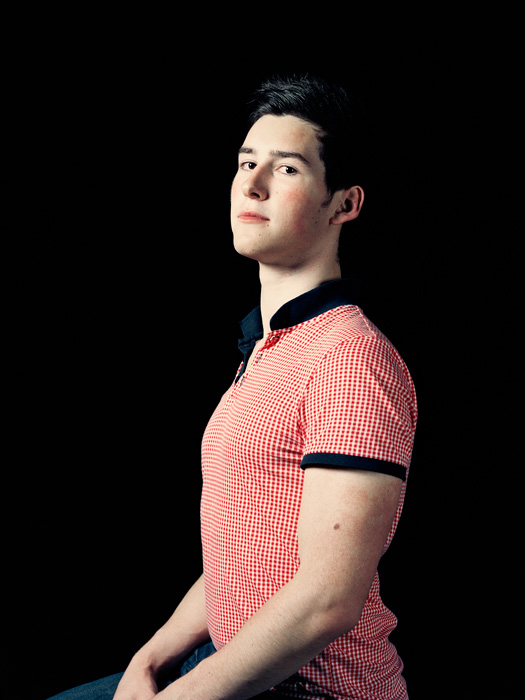

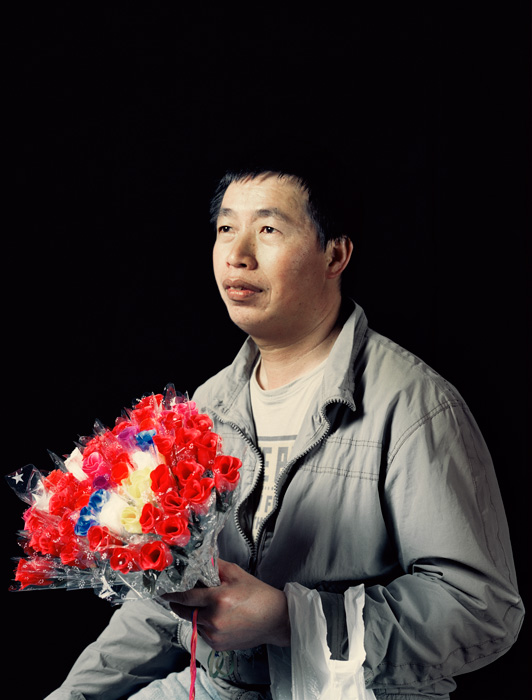

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, The Way of the Willows, 2013, série de 85 épreuves numériques / series of 85 digital prints, formats variés / various sizes. Permission de / courtesy of Galerie Donald Browne. Œuvre réalisée lors d’une résidence au CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, à Glasgow, en Écosse, en 2010 / Work produced during a residency at the CCA : Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, Scotland, in 2010, avec la collaboration de / with the collaboration of Emmanuel Galland, conseiller artistique / artistic advisor, et la complicité de / and the complicity of Brian Sweeney, photographe / photographer. Équipe de production / production team: Felicity Lamb, Scott Brotherton, Mairi MacKenzie, Garry Maclennan, Eve Traynor, Louise Shelley, Brigitte Henry, Janicke Morissette.

The Way of the Willows, vue dʼexposition / exhibition view, Galerie Donald Browne Gallery, mai-juin 2013 / May-June, 2013, photo : Jean-François Brière

In Glasgow, the artist Gabriel Coutu-Dumont set up a minimal photography studio on Sauchiehall Street, a street frequented by the city’s night owls. For several nights, he drew these passersby away from the tumult of the street and asked them to pose in front of an analog camera for a twenty-minute session. The result was The Way of the Willows, a gallery of eighty anachronistic portraits in which the classical composition contrasts with the signs of the models’ contemporary lives.

Isolation. Each portrait is reduced to a setting in a tight space, neutralized by the absence of a background. The bust-length figures appear in lighting that is direct and very bright, intensifying the relief features of the faces and folds in clothing. Each portrait is organized in a void, centring focus on the figure and excluding all outside elements. With his strategy of absence of context, Coutu-Dumont takes as a basis the common definition of the portrait, given by Jean-Luc Nancy as “the representation of a person considered for himself or herself,”1 to counter a sociologically dominated observation or a visual account of Glasgow’s night life. He creates unlocatable images, suspended in time. It is surprising to see Coutu-Dumont take such a stylistic departure from his photographic explorations in intimate (Sketches of Synchronicity, 2006–10), macroscopic (Black Holes, 2011), and distanced (Delta City, 2011) modes. Even though some of his photographic habits persist, such as “controlled plays on light, iconoclastic forms, and sound put into images,”2 the series The Way of the Willows takes a different path.

Quotation. The unadorned, anti-naturalist setting gives the image a texture and finish similar to seventeenth-century Flemish paintings. Immediately, the connection with painting comes to mind and interferes with our gaze as we look at the photograph: the quotation is unavoidable. The Way of the Willows borrows from the Dutch school its canons and strict codes: the figures are undemonstrative, bathed in a chiaroscuro, and reject the standing pose, considered a sign of vanity. This aesthetic, borrowed from Van Eyck or Rembrandt, complexifies the apparent neutrality of the photographic composition.

Anachronism. In referring to the genre of Flemish painting to construct his images, Coutu-Dumont opens his creativity both to a form of historicity and, especially, to anachronism. With this gesture, the artist crosses through time and revisits a defined history of art, which Georges Didi-Huberman describes as “an object of complex time, of impure time: an extraordinary montage of heterogeneous times forming anachronisms. In the dynamic and complexity of this montage, historical notions as fundamental as ‘style’ or ‘era’ are suddenly seen to have a dangerous plasticity (dangerous only for someone who would like everything to be in its place once and for all in a given era).”3

Beyond the images themselves, the way the works are displayed is anachronistic. On the walls, The Way of the Willows takes up the “cheek by jowl” hanging codes of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century French salons, featuring rows of works arranged in tight ranks. This gives the series a new density and coherence, with the effect of strictly sequential ordering counterbalancing the chaotic multiplicity of the faces. With this reprise of the historical portrait gallery, Coutu-Dumont evokes the classic grandeur of the salons rather than the desire for classification that motivated “ethnographic” portrait galleries in the early days of photography.

For the series to renew the idea of the portrait in the sense of the “traditional” portrait, we must go beyond the first unequivocal reading of the “Flemish” portrait. Essentially visual on its own, the pictorial quotation is insufficient to a consideration of how this series contributes to the redefinition of the photographic portrait today. It is Coutu-Dumont’s attachment to past photographic customs and historical picture-taking protocols that make his images so complex. Behind the aestheticized, glorifying obviousness of the portrait is hidden a multitude of the artist’s actions as he becomes both strolling photographer and people’s portraitist returning to a nineteenth-century tradition. The portrait genre is thus inseparable from the image of the photographer, defined counter to his era, no longer in the artist’s own time but more in the borrowing of a historical photographic gesture.

Painting and Photography. A second historical gesture makes its appearance in the effort at staging and dramatic lighting. It evokes late-nineteenth-century French pictorialism – in particular, the portraits and studies by photographer Constant Puyo,4 who claimed that photographs have the same aesthetic legitimacy as paintings. In referring to pictorialism as a possible source of The Way of the Willows, I must bring up the question of the ambiguous relationship that both unites and separates the genre in painting and in photography. Historically, the art of the photographic portrait has gradually pulled away from the pictorial model, inventing and refining its own vocabulary and influencing, in its turn, the genre from which it pulled away. Coutu-Dumont updates – with a certain detachment – the historical rivalry from the beginnings of photographic portraiture, when “heliographers” were accused of wanting to compete with painters in portraiture. Rather than revive a historically marked debate, The Way of the Willows follows a strategy of hybridization in which the genres of photography and painting overlap without confronting each other. Here, the artist brings to life the virtue of contemporary photography that Michel Poivert has described as “a more faithful inscription of photographic originality in its relationship with art, but also that of a position critical of art – that is, a new aesthetic.”5

Critical Position. Coutu-Dumont takes a position critical of the canons that convey the ostentatiousness and self-satisfaction of the portrait in its glory. He tries to induce a new form of glory, drawn from backwaters of nightlife, where naturalist snapshot portraits would be expected. In modern and contemporary photography, the glorifying portrait has not disappeared; nor has the social or ethnological portrait.6 Although Coutu-Dumont updates the former, he does not succumb to the temptation of the latter, a sociological portrait of a place through a sampling of individuals. He refuses to capture the human figure, to decompose it into a given number of profiles that would then be used for the purpose of classification. His series of portraits seems to be guided, on the contrary, by a visual statement, determined in the modern history of photography by multiple crossovers between the photographic medium and the visual arts. It takes a non-documentary position in which the photographic gesture is proposed as an interpretation of reality, distanced from all utilitarian applications and from the notion of the “decisive instant,” following the photography of the early 1980s.

The portrait’s autonomy is confirmed, detached from the event from which it is extracted. Stopping the motion of the human figure gives us time to gaze. It also shifts the photographic subject outside of time to invest it with visual value. For Coutu-Dumont, the aesthetic statement is supported by this almost obsessive search for anachronism. He combines outdated codes with current indices, and interprets the presence of these contemporary night owls through the prism of seventeenth-century pictorial canons, the popularized nineteenth-century portrait, or early-twentieth-century pictorialism. These anachronistic shifts create other references and unstable visual milestones that constantly evolve in the resonance among a number of eras. The portrait is thus essentially a question of time. The Way of the Willows offers a singular position that confronts the snapshot and the rapid unfurling of images today.

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 Jean-Luc Nancy, Le regard du portrait (Paris: Éditions Galilée, 2000), p. 11.

2 Press release, Galerie Donald Browne, Montreal, 25 April 2013, consulted online on 28 February 2014 (our translation).

3 Georges Didi-Huberman, Devant le temps. Histoire de l’art et anachronisme des images (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, “Critique” imprint, 2000), pp. 16–17.

4 Founder of photo-club de Paris in 1888 with the photographer Robert Demachy.

5 Jean-Marc Huitorel, “Michel Poivert. La Photographie contemporaine,” Critique d’art [online], 21 (spring 2003), put online 27 February 2012, consulted 28 February 2014, critiquedart.revues.org/1951.

6 See Anne Biroleau, “Le visage en question – La representation,” in Sylvie Aubenas and Anne Biroleau, Portraits/Visages (Paris: BnF and Gallimard, 2003), consulted online 28 February 2014, expositions.bnf.fr/portraits/arret/2/index2.htm.

Claire Moeder is an author and art critic. Since 2010, she has reported on exhibitions (ratsdeville) and has had articles published in the magazines esse, Zone occupée, and Marges. She has contributed to the Mois de la Photo à Montréal catalogue de 2009 and to a monograph on Christian Marclay (2009). As a young curator, she had a residency at the International Studio and Curatorial Program (New York) in 2013 and organized the exhibition Sayeh Sarfaraz. Micropolitiques à la Maison des arts de Laval.

Gabriel Coutu-Dumont, born in Montreal in 1978, is a multidisciplinary artist who also works in collectives (RACAM, nAnalog, and Silent Partners) and collaborates with organizations (Mutek). His solo work has been featured in a number of exhibitions in Canada and abroad, including, notably, Sketches of Synchronicity. The Way of the Willows will be reprised at Centre VU in Quebec City in 2015, accompanied by a book currently in production at Éditions Sagamie. Coutu-Dumont is represented by Galerie Donald Browne, in Montreal. www.gabrielcoutudumont.com

Purchase this article