Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto

Guest Curator: Bénédicte Ramade

An interview by Jacques Doyon

On September 14, 2016, the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto inaugurated an exhibition titled The Edge of the Earth – Climate Change in Photography and Video, featuring works by more than twenty contemporary artists from Canada and abroad, as well as press photographs from the celebrated Black Star collection. Curated by Bénédicte Ramade, a specialist in environmental art living in Montreal, The Edge of the Earth focuses on contributions by various artists and journalists to the recognition and consideration of issues linked to climate change, with a particular emphasis on the challenges posed by recognition of the central role played by humans in the disruption of their environment in what is now known as the Anthropocene Era.

JD: You wrote a doctoral dissertation and have produced several exhibition projects related to environmental questions. What path or circumstances brought you to this most recent project? What is its origin?

BR: My doctorate was devoted to the inception of American ecological art in the 1960s and its development over three decades. This little-known movement has been overshadowed by Land Art, with which it is often erroneously compared. I undertook to write a critical history of this art movement in conjunction with that of American environmentalism in order to show the relevance of these practices, even if they had their problems.

In parallel with this work as a historian, I began to be interested in contemporary ecological practices (both artistic and curatorial) and to question their performance on the ecological and political levels. This led me to organize Acclimatation, with the Centre d’art de la Villa Arson in Nice in 2008; it was my first exhibition on the issues of artificial nature – or, as I call it, humanature. All of the spaces were devoted to an intuitive, and implicit, very versatile narrative built through works by about thirty artists, some of them clearly engaged in ecological issues and others without a position. The ethical stance of this exhibition was to not try to be a science museum or be dogmatic, so that the public had the freedom to apprehend things of nature. The fundamental mechanism of my exhibitions is the deconstruction of the public’s presumptions – the expectations generated by certain keywords, such as “nature” and “ecology.” Therefore, my second exhibition, Rehab, at the Fondation EDF in Paris in 2010, worked with the notion of recycling in the same way. As soon as the word “recycling” is uttered, everyone has a preconceived idea about it. I wanted to pick apart this mechanism and ask people to consider the fact that recycling is not always so very virtuous on the ecological level. We continue to be huge consumers of bottled water because the thought that the bottles will be recycled is reassuring. But recycling uses a lot of energy and requires a lot of water. An artwork by Tue Greenfort, 1 kilo PET, explained it perfectly.

The Edge of the Earth in Toronto works on a similar principle. Climate change, whether you believe in it or not, almost involuntarily evokes images and ideas among visitors. People think they know what might be exhibited in a show devoted to climate change. They have information; they expect certain standard presentations (images of catastrophe, “National Geographic” moments showing the resiliency of nature). But at the dawn of the Anthropocene Era, the geological period in which humans have become a considerable disruptive force at the telluric scale, it seemed to me that we should change visual paradigms. If this geological era is adopted by the scientists, it will make nature and culture inseparable. Theoretically this is already so, but in fact Western humanity continues to disassociate itself from nature. Up to now, this attitude has not garnered good results. The Anthropocene Era is shaking up our paradigms, forcing us to assume full responsibility for humanity’s actions. Of course, for the moment, it is in its early stages, promulgated by theoretical and ethical debates, but this period of genesis is already full of passion and bursting with publications. Visual artists such as Julian Charrière and Isabelle Hayeur have already perfectly grasped the issues at stake in this era.

JD: This project deals with the way in which climate-change issues have been addressed and highlighted in photographic and videographic production from the late nineteenth century to the 1970s and up to contemporary times. Can you point out some major landmarks and transformations of environmentalist representations?

BR: The core of the exhibition is built from images from the Black Star collection – press photographs that date mainly from the 1970s, the golden age of media coverage of environmental deterioration and of the history of environmentalism (brought on by the oil crisis). It was striking to observe how the visual models built during this decade were still being used not only in the press but also in what might be called environmental photography.

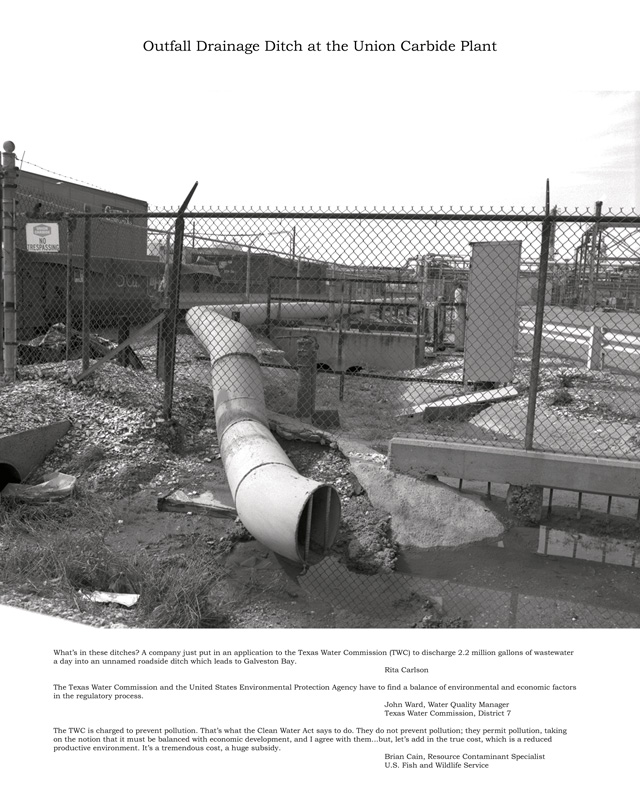

For instance, the saturation of the photographic frame with accumulations of trash, car carcasses, tires – the covering up of sites – constitutes a first group of iconographic markers. To these close-up views that play on the logic of visual oppression are added landscape views in which a visual “error” will be identified, the sign of a dysfunction that is not the result of the catastrophe but an account of a normalized ecological anomaly. Whereas press photography is the most immediate and dominant platform for disseminating information about and views of industrial accidents and climatic cataclysms, environmental photography operates in the context of catastrophic situations that are not necessarily linked to events, such as the tragic consequences of oil extraction from the tar sands. Finally, we must add to this imagery the human side of the ecological disaster, mainly through portraits of victims of climate change.

The ecologically sensitive and critical approach to landscape photography and nature photography is a direct descendant of this press coverage, starting in the late 1970s. Edward Burtynsky, Peter Goin, Richard Misrach, and Sharon Stewart were among the pioneers of environmental and activist photography. They will be represented in the exhibition. It was fundamental to present such approaches. Although it seems important to me to envisage a new step in environmental photography, they are not yet obsolete. I see some series, such as the ones by Stewart and Goin, as absolutely indispensable to the project. On the other hand, the oldest link between defence of the environment through the creation of national natural parks in United States and photography, which dates back to 1872, is not in the exhibition but structures my essay in the catalogue. It is important to remember this link, but we have already seen this too often. The link with press photography is less well known.

JD: It seems that the notion of environmental art is in fact the subject of debates and intense discussions. What is it exactly?

BR: There is not really a scholarly and critical consensus around the label “environmental photography,” as a recent symposium in Berne showed yet again. That event concluded with a profound challenging of the very nature of this genre of photography. There was also lively debate over photographers’ use of the mechanics of the sublime and of the sublimation of ecological catastrophe. Some critics, such as Paul Lindholdt, even called certain images “eco-porn,”1 reproaching them for relying on the spectacular nature of the large format, a strategy of visual shock, and aestheticization of critical situations to construct a discourse of awareness.

“Environmental photography” is torn between an activist documentary model and more or less catastrophic landscapes. The question of the beautiful and its compatibility with ecological ethics and political meaning are constantly discussed. The genre also faces a constant in the ecological domain, which is that the local and topical nature of an environmental problem must be interwoven with its global and symbolic scope. The very subject of this type of photography involves politics, science, ethics, history – there are so many levels. Photographers find themselves having to fulfil the mission of sentinel, journalist, activist, or scientist, or sometimes all of them together. The task is far from clear. There can therefore be no consensus over the identity of the environmental photographer.

JD: The exhibition is divided into different subthemes (“Listen to the Landscape,” “Humanature,” “The Anthropocene,” “Climate Control,” “Under Pressure,” “Breaking Nature”), which seem to fall within or combine different levels of approach, in a mode that is reminiscent of Borges. So, what was the structural logic behind this division – and very likely also behind the selection and grouping of works?

BR: As I have done in previous exhibitions that I organized, I am connecting clearly political and environmental works – such as those by Sharon Stewart, an activist photographer who, during the 1990s, created a visual inventory of the damage caused to the population and territories of Texas by the petrochemical and nuclear industries (The Toxic Tour of Texas) – to other, much more elliptical ones. For instance, Hicham Berrada’s work Celeste, which was also chosen for the catalogue cover, portrays a blue explosion, offering a sublime and ambiguous moment of catastrophe, as the spectator knows neither its cause nor its consequences. The spectator is invited to project, extrapolate, imagine. The work is open, between an homage to Klein and a demonstration without an objective for a claim. The entire exhibition is designed based on exchanges, principles of contamination, interference, and also dismantling, between implicit contemporary works and others, most of them more historical, that are more explicit in their desire to take action on the environmental question.

The Anthropocene era has been instigated mainly by humans; events can no longer be independent of us, but are linked to our presence, our history. That is why this movement of exchange within The Edge of the Earth leads to our finding ourselves at the centre of interpretation; we must take responsibility for inventing, diverting, accepting certain information while producing more personal content through these images and videos. I hope that the exhibition will stimulate something highly intuitive for visitors and not a didactic visit from which they must draw facts, causing the images to act more like evidence than artworks. Each section is physically very open – the exhibition space has been structured without partitions for this reason. Visitors are free to move and shift among the sections.

An exhibition space is by nature an artificial place, separated from the world by its white walls and controlled atmosphere. I don’t claim to break with this unreality – on the contrary, the visit should offer viewers the possibility to speculate, to free themselves from the tyranny of the information that conditions climate change outside, in the real world.

JD: The core of your project seems to involve an urgent appeal to update the ways that environmental issues are represented in order to meet the challenges of climate change in the Anthropocene Era. So, what would be the main avenues for such an updating? What current works could bring such a change to reality?

BR: Literature has already been addressing ecology for a long time – through fiction. Recently, Benjamin Kunkel signalled the advent of climate-change literature in an article in the New Yorker.2 In 2015, Adam Trexler published a study called Anthropocene Fictions: The Novel in a Time of Climate Change.3 Art has remained apart from this movement in a way. But the Anthropocene Era, through its profound nature, is reuniting humans with Earth; it allows, and even requires, imagination – no longer simply information – about environmental disturbances.

When Julian Charrière made an alpine mountain out of flour in a vacant lot in Berlin, he understood perfectly that all of this had to do with belief. He also brought humour and mockery of human vanities. With his retro-future cloudy skies, Nicolas Baier offers a particularly polished and pertinent form of comprehension of our situation today. His images have an incredible ambition if we look at them from an Anthropocene point of view. They are vertiginous, combining hard facts with visual speculation. They’re perfect, in the same way that Isabelle Hayeur’s constructed landscapes are perfect.

These are the pathways that I offer visitors to The Edge of the Earth. I am not expecting this exhibition to take on the disproportionate mission of resolving anything in terms of climate change. It brings us back down to Earth because that is where the problem of climate change starts and where the most critical effects are felt. Earth is being driven over the edge; it is this critical fringe that constitutes the territory of the exhibition and its narrative, which I hope is fertile for those who take its measure. Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Benjamin Kunkel, “Inventing Climate-Change Literature,” The New Yorker, October 24, 2014.

3 Adam Trexler, Anthropocene Fictions: The Novel in a Time of Climate Change (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2015).

Bénédicte Ramade holds a PhD from Sorbonne University (Paris, France), specializing in the history of ecological art in the United States (The Misfortunes of Ecological Art in the U.S. since the 1960s. Proposition for a Critical Rehabilitation). In 2009, she curated the group exhibition Acclimatation at Villa Arson (Nice) and edited the accompanying catalogue, which analyzed the relationships between nature and culture. In 2010–11, she addressed the idea of recycling in contemporary art practices in the group exhibition Rehab, The Art of Re-Do, at Fondation Edf (Paris). She lives and works in Montreal. She is a lecturer in art history at Université de Montréal, where she has been awarded a postdoctoral fellowship.

Jacques Doyon is the editor and publisher of Ciel variable magazine.