[Spring-Summer 2017]

Focus Perfection

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

September 10, 2016, to January 15, 2017

By Philippe Guillaume

The Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition Focus Perfection, which opened last fall at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, was a lavish retrospective dedicated to the controversial New York artist who took up photography in 1970 with a borrowed Polaroid camera. Three decades after Mapplethorpe’s first retrospective show, The Perfect Moment, held at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1988, the MMFA’s neoclassical pavilion provides a perfect setting for the photographs by an artist whose fascination with the Euclidian form and the classical dominates and whose subject matter remains provocative, even in the age of cyberporn. The visitor climbing the museum’s Vermont marble central stairs was immediately faced with an imposing deadpan self-portrait: Mapplethorpe’s chiselled and perfectly groomed rock-star gaze dominates the hall entrance. Certainly, this was a spectacular way to initiate an exhibition of works by one of the best-known photographers of the second half of the twentieth century, who, self-avowedly, was obsessed with leaving a towering legacy in the realm of high art. Indeed, art-history critic Douglas Crimp sees Mapplethorpe’s work as a “modernist appropriation of style”1 that “continues the tradition of museum art.”2 His death in 1989, following a battle with AIDS, contributed to public awareness of the disease.

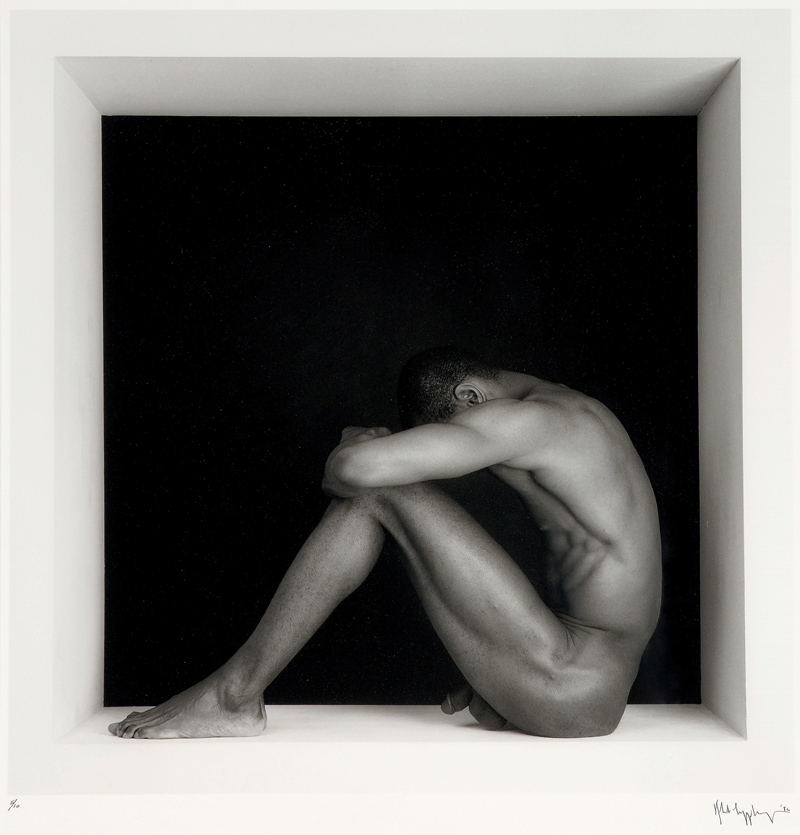

In his analysis of Mapplethorpe’s first retrospective exhibition, at the Whitney in 1988, American philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto evoked the Heideggerian notion of Geworfenheit, which translates as “thrownness”3 and connotes the idea of being hurled into a situation. For example, “The [Whitney] exhibition was so structured that one could not escape the experience: it was upon one before one knew it, and one had to deal with it as best one could.”4 By contrast, the curators of the Montreal exhibition took great care that the spectator would experience clarity throughout the viewing experience. The MMFA exhibition presented a carefully curated scenography that spanned several galleries, some with embedded spaces providing intimate thematic hubs, such as the one dedicated to Mapplethorpe’s Polaroid work. The walls displayed classically framed photographs alongside large wall cards bearing quotations by the artist and by collaborators such as Patti Smith and Susan Sontag, among many others. Everything was arranged to offer viewers an experience that was as much about information as about art. Indeed, to benefit fully from the show was to appreciate this body of work as more than art photography. In his work, Mapplethorpe dealt with aspects of gender, gay culture, queer culture, the 1970s and 1980s in New York, controversy, pornography, aesthetics, the senses, and censorship, to name only some of his topics. The curators obviously went to great lengths to bring forward the exhibition’s educational potential, as evidenced by the numerous informative texts that covered the walls throughout the large ambulatory that led to the exhibition’s galleries. Although his explicit photographs of homoeroticism and the underground BDSM scene in New York during the late 1960s and the 1970s have proven disturbing for many since they were first displayed, Mapplethorpe is recognized as an avatar of photographic art in America. Sexuality and nudes are a primary and recurrent theme throughout his portfolios, but, as this exhibition demonstrated, it would be an error to limit a critical appreciation of his work only to its controversial motifs.

The Montreal exhibition included an introductory gallery, in which viewers could learn about Mapplethorpe through texts, a video in which he talks about his work, and some of his self-portraits. It also included portraits of Mapplethorpe by other artists and photographers, such as a 1983 dye-diffusion print by Andy Warhol and a 1980 black-and-white picture by David Bailey. The next room was the most crowded: display cases with contact sheets, record jackets, and Polaroids; a video of the artist at work in his studio; portraits of artists and celebrities, including Philip Glass and Debby Harry; and a large section dedicated to his work with his close friend Patti Smith. A long, dark corridor flanked by two rooms was dedicated to Mapplethorpe’s nude studies. The lateral spaces included the X Portfolio, which was his “attempt to legitimize his sex pictures in a fine-art context.”5 The exhibition’s emotional peak occurred in the next gallery, which housed the floral and sculptural still lifes that Mapplethorpe constantly photographed during the last two years of his life and was enveloped in a dramatic opera soundtrack. This section included some of his dye-transfer prints of flowers that convey a fixation with perfection that is as sharp in his colour photographs as in his platinum prints. Following photographs of his muse, Lisa Lyon, and his model and lover, Philip Prioleau, the last three photographs in the exhibition – Dollar Bill (1987), Coral Sea (1983), and American Flag (1977) – conveyed an eerie imperialist finale to an exhibition that contributed to Mapplethorpe’s mythical status.

Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium was first presented in Los Angeles in 2016 successively at the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the two institutions responsible for organizing the show. The curators were Paul Martineau and Britt Salvesen, who started working on the project in 2011. The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts version was curated by Diane Charbonneau under the direction of MMFA chief curator and director Nathalie Bondil.

2 Ibid.

3 Arthur Danto, Playing with the Edge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 10–11.

4 Ibid.

5 Paul Martineau and Britt Salvesen, Robert Mapplethorpe The Photographs (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum), 56.