[Fall 2018]

By Ellen Tolmie

A recent show at the Ryerson Image Centre (RIC) challenges conventional notions of the lone photographer, the roles of subjects, and even the exhibition space. The idea of the photograph made by an individual, the photographer, now also lionized as artist and auteur, has long been embedded in the essential idea of what photography is. As photography of all genres gained decisive entry into the art world in the late 1970s, the photographer artist as solitary hero or heroine was further entrenched. As photographers joined the pantheon of artists, their creations came to be perceived as singular achievements, the finished products of an ultimately solitary endeavour. It is the art equivalent of the capitalist self-made man, and we have all bought into it.

Collaboration, A Potential History of Photography 1 modestly and magnificently challenges this notion. When I first heard about the project several months ago, its subtitle, positing an alternative history of photography, seemed more than a little presumptuous. But after I viewed the exhibition, its premise seemed self-evident. By asking us to consider the subjects in photographs as integral to their creation – as participants, even if coerced, rather than primarily as objects of the artist’s commanding gaze – Collaboration proffers a critical re-envisioning of conventional assumptions about photography.

Photographs, like other visual representations, have long favoured the privileged white male view of the world, a perspective that post-modernism and identity politics have steadily chipped away at, with still-incomplete results, for almost a century now. So, it’s not surprising that an exhibition challenging the centrality of a sole-author photographer in favour of collaborative authorship that includes the subject – art’s ultimate “other” – is conceived and curated by women: Ariella Azoulay, Wendy Ewald, Susan Meiselas, Leigh Raiford, and Laura Wexler.

Collaboration is also a difficult exhibition. It is arranged in eight thematic grids of copies of images – no archival or master prints here! – with individual squares profiling different photography projects that examine each theme. An acknowledged work in progress, this is its third iteration (the first was at New York’s Aperture Gallery), and it requires time and effort to navigate. But it’s worth it. By radically challenging the norm of authoritative finished works on gallery walls, the format, like its content, disrupts. The grids are temporary assemblages to be moved, refashioned, or discarded. Blank white squares in each grid represent what is still missing. Empty grey squares mark the few instances in which a photographer or subject declined to be in the show.

The exhibition also includes several “What’s missing?” tablet booths inviting visitor comments and a large, centrally placed table lined with chairs, with reproductions of the grids, books in which many of these images appear, and other materials around which casual viewers, students, and others may congregate and, potentially, challenge what they see. The premise of Collaboration thereby extends to the viewer, opening the exhibition space to a more genuinely interactive dynamic.

The first grid presents the over-arching concept, The photographed person was always there, introduced with a square on Alfred Stieglitz’s famed photographs of his lover, the artist Georgia O’Keeffe. Quintessential examples of a favoured subject of the dominant male gaze, they also illustrate the critical role of subject-as-collaborator, without which the images would have no power. Below this are examples of Edward Curtis’s equally famous images from his multi-year project (1907–30) portraying North American indigenous peoples. Posing in costumes and re-enacting scenes belonging mostly to their past – so, actively contributing to these constructed representations – Curtis’s over a thousand subjects were essential collaborators, despite their reported suspicions of his motives and his romanticizing of a past that his dominant white culture was bent on destroying. Both examples testify to the complicated power imbalance between subject and photographer.

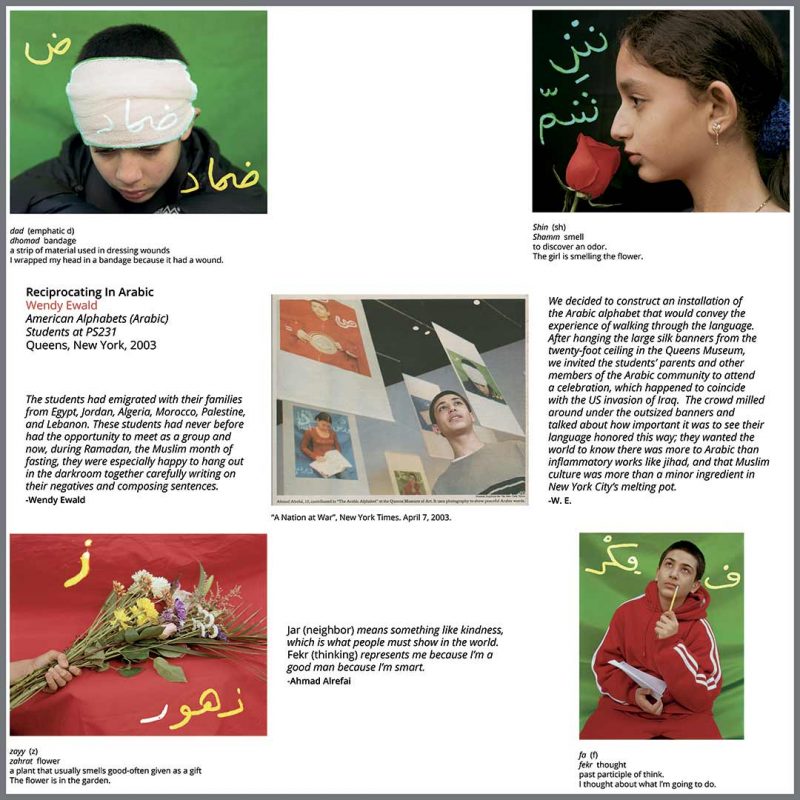

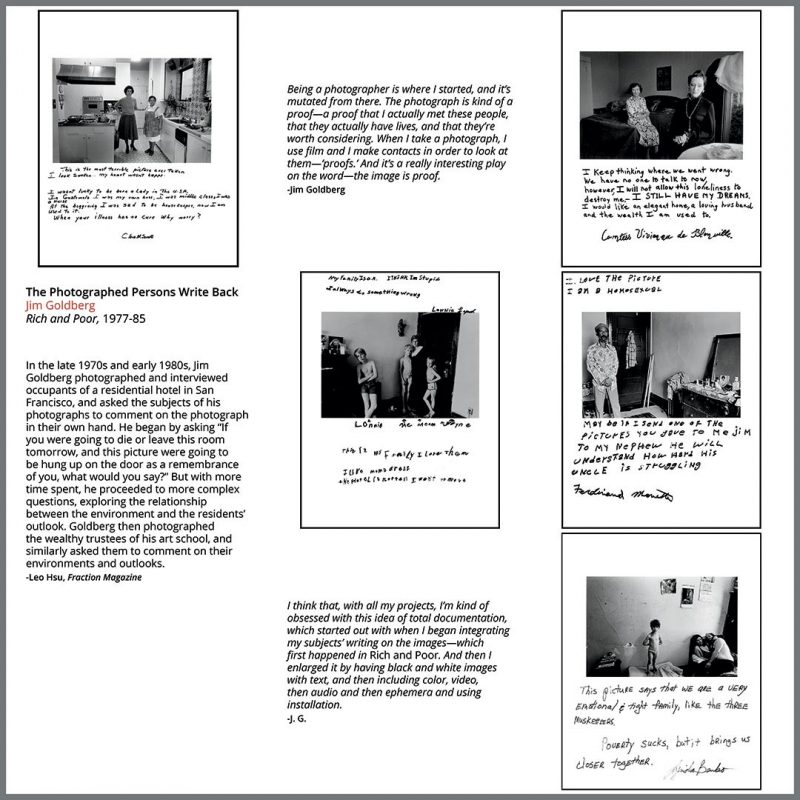

Collaboration is the brainchild of Ewald and Meiselas, American photographers who have long sought to engage their subjects in a consciously collaborative practice. Ewald has done this for over forty years, having pioneered a workshop format of image-making with marginalized children and other vulnerable people in the United States and many other countries, mixing her own images with those by her putative subjects.

Meiselas, widely known since her in-depth coverage of Nicaragua’s 1978–79 Sandinista-led revolution, had also previously experimented with ways to involve her subjects in her practice. Since the Sandinista uprising, when several of her photographs became iconic totems of that event, she has returned frequently to Nicaragua, including with billboard-size reproductions of some of these images. Filming, photographing, and interviewing, she queried her subjects’ perspectives on these representations and examined the independent afterlife that some images had attained, their varied impacts on both their immediate subjects and their communities, and their role in upholding or distorting memory and history. Meiselas’s other work has likewise engaged her subjects; she undertook a massive collaboration with the Kurds in the 1990s to assemble an online archive of family, current, and historical photographs and related evidence of their perpetually under-siege community.

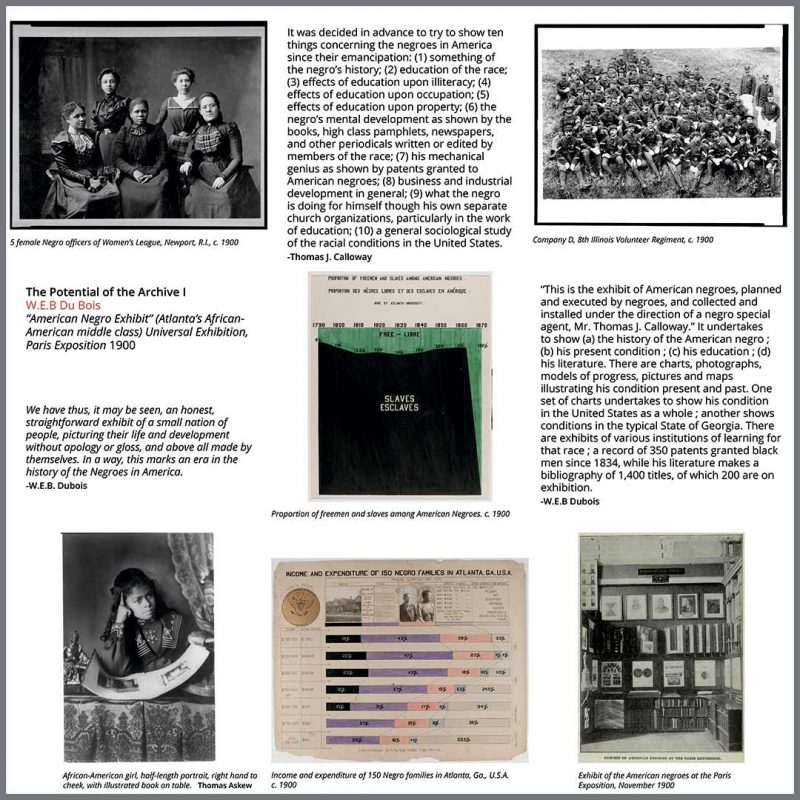

Several of Ewald’s and Meiselas’s projects are represented in Collaboration. Their concerns led to exchanges with other photography curators and scholars. Azoulay, the only non-American, is an Israeli shaped by the Israel–Palestine conflict and the disjunctive, often opposing messages conveyed by the images that record it. She has asserted a “civil contract” obligation for the act of photographing, the resulting imagery, and its subsequent dissemination, challenging any assumed neutrality along the way. Leigh Raiford examines race and justice issues through their layered expressions in visual representations, particularly as they affect African Americans. Laura Wexler dissects visual culture’s interpretation of, and impact on, the intersections of gender, race, sexuality, and class. In Toronto, both practitioners and scholars are joined by a RIC team that includes additional guest curators and Ryerson’s School of Image Arts, where a months-long series of walk-throughs, lectures, workshops, and classes has been organized.

Other Collaboration grids explore efforts, like Ewald’s, to make images with their subjects, extending, as the text advises, the “instantaneity of the encounter” into a deeper engagement. One focuses on the duality of violence in images. It profiles photographs intended to unmask violence, as in Donna Ferrato’s ground-breaking 1980s documentation of domestic violence, and other images that were part of the violence. These include the forced photographing of protesting British suffragists at the turn of the twentieth century; Algerian women in 1960, their veils removed, during their country’s war of independence from France; and the victims of Cambodia’s genocidal Khmer Rouge (1975–79), who took mug shots of their prisoners before killing them. The forced images, their subjects powerless but somehow defiant, got away from their makers: now they read as clear indictments of the perpetrators. Here, the images’ afterlife has repositioned their subjects’ coerced collaboration into a form of resistance. Another grid deconstructs famous image icons with counter-images of the subject that tell a deeper story or even contradict the icon, photographs that the curators call “potentially iconoclastic.” One examines Kim Phúc, the Vietnamese girl photographed in 1972, running naked, screaming, wounded by napalm. She is now a Canadian, and a 1995 image shows her deeply scarred back as she embraces her infant son. Still other grids explore less-well-known subjects, individuals, and communities seeking to better control their images in order to reclaim their stories, advocate against injustices, and grapple with the dilemmas of image surveillance and targeting, the value of privacy and witnessing, and the shaping of photographic archives and the versions of history that they sustain.

The iterative nature of Collaboration explains its unevenness, with several ponderous texts and arguments and image segments some of which are more convincing than others. A separate wall of exploratory statements is also available as a takeaway printout. Part exposition – “We are using the grid as a transitional form while we seek both a structure and an open foundation for the dynamic study and display of collaboration” – it too often veers into the impenetrable. The preponderance of American image content is a bias that the curators acknowledge and invite challenges to.

My receptiveness to Collaboration is related to the more than two decades that I directed UNICEF’s global photography program. There, with limited success, we worked with others, including many photographers, to promote more nuanced and respectful visual representations of children that protected them as needed but also sought to illuminate their complexity and subject-ness (rather than their being objects of aid or aid promotion). This was in addition to the challenges of distance, poverty, and cultural and racial difference that their depiction, for global distribution, also entailed.

Like other “others,” photographed children in all genres are frequently objectified, satisfying adult needs and visions that rarely acknowledge them as the often-coerced participants in the creation and use of their images. Critiques of this are growing and deepening, and photographs by children, of themselves and their worlds, are also increasingly valued (Ewald has critically contributed to this). Still, there is a long way to go to counter the rank clichés. Collaboration references one origin of this problem (just above the opening Stieglitz–O’Keeffe images): Julia Margaret Cameron’s famed nineteenth-century efforts, soon after the advent of photography, to depict restless children as the angelic embodiments that her sentimental tableaux demanded.

I remarked to RIC director Paul Roth that the integration of the exhibition’s challenges into photography studies could do much to nurture a generation who would embrace photography as essentially collaborative rather than an artist’s solitary pursuit. “Maybe,” he replied, perhaps evincing scepticism that such a core premise could be readily dislodged. Presumably, one resistant constituency is the prevailing art culture that profitably promotes the lone photographer as celebrity-adventurer. In his statement opening Collaboration, Roth also pointed to a small ancillary exhibition, Cash Machine by French artist Sophie Calle, that presents surveillance images of a man withdrawing cash from an ATM. Such auto-recording precludes authorship by either a human photographer or its subject; Calle interprets but didn’t make the source imagery.

This raises the disturbing prospect that it may be too late to reframe the social contract in the making or viewing of images, in an age when billions of human- and machine-made photographs are manufactured daily. But we are committed storytellers, and our images, like words, have forever been used to obscure and manipulate as often as to reveal and elucidate. These are political choices, as Azoulay argues, that demand a constant re-examination of our narrative tools to claim them for less exploitative, richer experiences.

Kudos to Collaboration’s many authors and to the RIC for offering an insightful and open-ended forum to reflect on the complicated realm of the photographic image that captures and enthrals us all.

Ellen Tolmie writes on documentary photography and other social issues. She directed UNICEF’s global photography work from 1990 to 2013 and has contributed to a variety of publications and forums on the subject of visual representations of children, including the books The Rights of Children(2009), Full of Grace(2007), and The End of Polio (2003). Earlier, she was an editorial and documentary photographer in Toronto, New York, and Bogotá. She currently lives in Toronto.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 110 – MIGRATION ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Ellen Tolmie, Envisioning Photography as Collaborative ]