[Fall 2018]

By Sylvain Campeau

Presented in this year’s edition of the annual Scotiabank Contact Photography Festival in Toronto, this exhibition was probably the festival’s centrepiece.1 It is a collection of works that seem to emanate from two series produced by Irish photographer Richard Mosse: The Castle, from which no doubt the most important pieces have been selected, and Incoming, a video work showing only a series of photograms. An extensive grouping of these is also in a book that Mosse published in 2017.

As he had first done in 2011 and 2013 for Infra and The Enclave, Mosse uses a military tracking technology. In those series, it was an infrared film camera capable of detecting human presences in dense foliage. This time, it is a video cam era able to capture the thermal signature of a human body in relation to the climatic conditions of its immediate environment. Considered an element in the panoply of technological weapons, this camera, made by a military arms manufacturer, is protected by an international legal instrument known as the International Traffic in Arms Regulations. This classification made it difficult for Mosse to cross borders, which was a prerequisite for the project that he wanted to pursue with the technology.

It was once again to make a portrait of difficult human conditions that Mosse used this special image recording device. It was a war in Africa for The Enclave; this time, for The Castle, he was interested in human displacements caused by other confrontations. In this series, the images are of refugee camps located in various European nations.

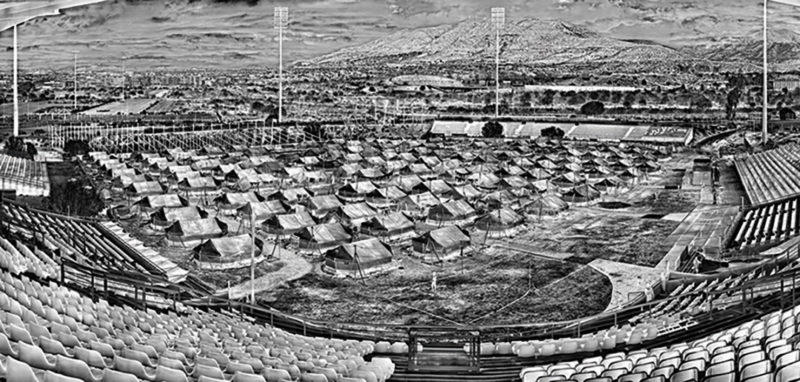

The remote point of view from which the images of these habitats were rendered was obviously due to the fact that he could not approach the camps. The combination of the camera’s range and Earth’s curvature also contributed to the need to be at a distance. With this camera, which can detect the human body at a distance of 30.3 kilometres, he captured them, from an elevated position, in images that owe much to the state-of-the-art technology: the shots were taken with a super-telescopic lens, attached to a camera capable of thermal sensitivity, activated by a controlled-motion robotic arm. One video in the exhibition, Grid (described below), gives a striking idea of the results obtained with this equipment. The lens allows him to capture images in a tight frame, in a sort of visual cell in which are contained refugees waiting for regularization. The large formats that we see in the galleries are therefore the recomposition into a single image of these myriads of truncated shots, woven together to create a complete, overall view, encompassing the camp as a whole.

With this technology, the images vaguely resemble negatives or solarized prints, which would have been subjected to strong light during development, as was done (by Man Ray, for one!) in the era of analogue photography. The effect is an environment with clean lines and accentuated reliefs, within which human silhouettes also stand out clearly. But that is all they are: black-and-white figures in rudimentary living conditions. These human presences, faces and silhouettes, look ghostly, milky, all distinctive features wiped away, in an unclear rendering and submitted to the objective of being accounted for purely mathematically. The apparatus tells us where these human subjects might be and how many there are, as long as we have no interest in who they are as individuals. It is enough simply to count them this way; because they are dislocated, torn from their usual environment, they appear, as such, to have no identity.

In addition, the tents and barracks thrown up randomly, in a remarkable human concentration, show an incongruous effort at accommodations. The edges of the camp often seem hazily defined, whereas various activities, performed by legal citizens, are underway on the surrounding area. In Skaramaghas (2016), they are transporters close to what seems to be a site of debarking, port or train station. In Souda Camp, Chios Island (2017), it is a beach with bivouacs crammed together between a rocky shore and the sea, divided into lots on a pebbly shoreline. We get a good sense in these images of the heavy burden of this existence on the fringe of the daily life of legitimate inhabitants, in the view of whom these wanderers no longer have the right to anything but a perfunctory existence, barely covered by notions of human rights, because they have fled states in which their lives were imperilled. Outside of their distressed home country, their refugee status confines them to a limbo between nation-states.

Certainly the most impressive image is Hellinikon Olympic Arena (2016). Here, the tents have been pitched in a stadium and we can only feel uneasy as we look at the seats in the foreground, which position us as spectators to this human misery. Having chosen to produce an image in this site is to highlight a paradox. Greece is the cradle of Western civilization; it is where Plato wrote The Republic. An early form of democracy was conceived in the surrounding area. It is also the country where the Olympic Games – that great festival of human fraternity – were born.

We might nevertheless choose to pay no heed to the intentions behind the invention of this technology and decide to adopt a more idealistic point of view. Is it not appalling to think that this camera can, even at a great distance, capture human thermal signatures? It is tailor-made for this purpose: to seek out human heat. We understand well that its aims are control and surveillance, especially of subjects like these. And yet, from the images emanates a sense of fragility. We can almost imagine that in some of them we see the blood vessels, the irrigation of veins, under the diaphanous skin, beneath the erasure of the unique features and the identity of those who have been its targets. But, at the same time, we sense the vital instinct that moves these wanderers – their resiliency, their survival reflex, their attempt at organization on the margins of the modern states that ignore them. In these bloodless bodies, there is something that beats and pulses, obstinately. Something that persists and strives.

Our idealism stops short, however, before the wall of screens comprising Grid (Moria) (2017), a camp on the island of Lesbos, Greece, where the living conditions are particularly difficult for the migrants. The work is made up of sixteen screens that showcase the type of capture that the technology used by Mosse allows for. The cameras are mobilized by a robotic arm that moves, jerkily, from left to right over a few seconds, imperceptibly showing the same scene again and again, but in a bumpy horizontal pan. This patrol-sweep, with its technical and expressionless meticulousness, reminds us of the imperative of surveillance. This work also shows how the mechanism that enabled Mosse to harvest the raw material for his photographic images, each composed of a mosaic of these shots, functions.

Other works are added to these and offer an overview of the video, Incoming, a fifty-two-minute piece co-produced by the National Gallery of Victoria, in Melbourne, and Barbican Art Gallery, in London, that Mosse has shown on other occasions. Whereas most of the exhibition is devoted to works showing overall views of these camps, with Incoming Mosse seems interested in a closer look at the migrants as such, and their experiences of forced displacements. At least, that is what the few images offered to us show – shots taken live at certain poignant moments of these forced migrations.

The Castle, on the other hand, offers the spectacle of their collective uprooting. [Translated by Käthe Roth]

Sylvain Campeau contributes to numerous Canadian and European magazines. He is also the author of the books Chambre obscure: photographie et installation, Chantiers de l’image, and Imago Lexis, as well as five poetry collections. As a curator, he has organized some thirty exhibitions.

Richard Mosse is an Irish conceptual documentary photographer. He has worked in Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Palestine, Haiti and the former Yugoslavia, but is best known for his images, in infrared, he did of the war in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Mosse received the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize in 2014, and the Prix Pictet in 2017. He has studied English litterature, cultural studies, fine arts in London, and received an MFA in photography at Yale. He now lives between New York and Berlin, and is represented by the Jack Shainman Gallery, in New York.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 110 – MIGRATION ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Richard Mosse, The Castle – Sylvain Campeau, Human Traces ]