[Spring 2003]

Musée d’art Contemporain de Montréal

February 22 to April 28, 2002

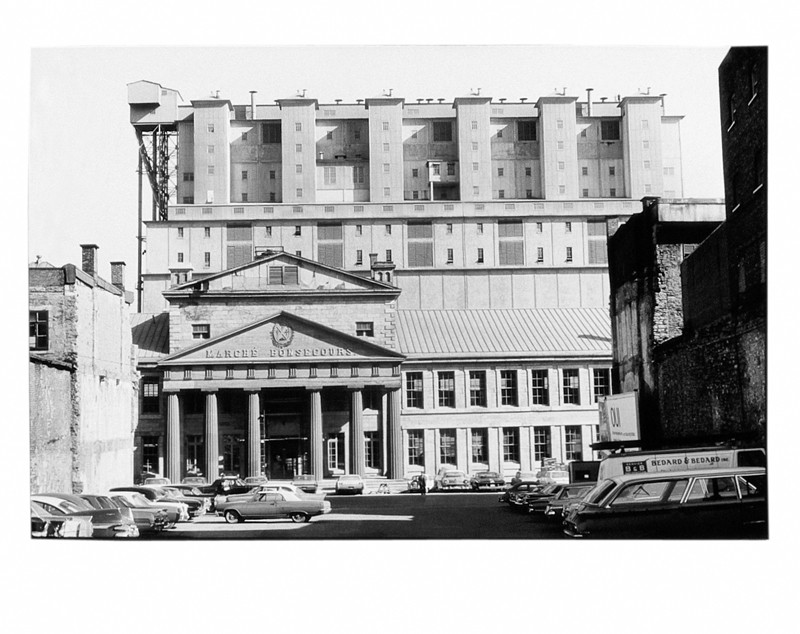

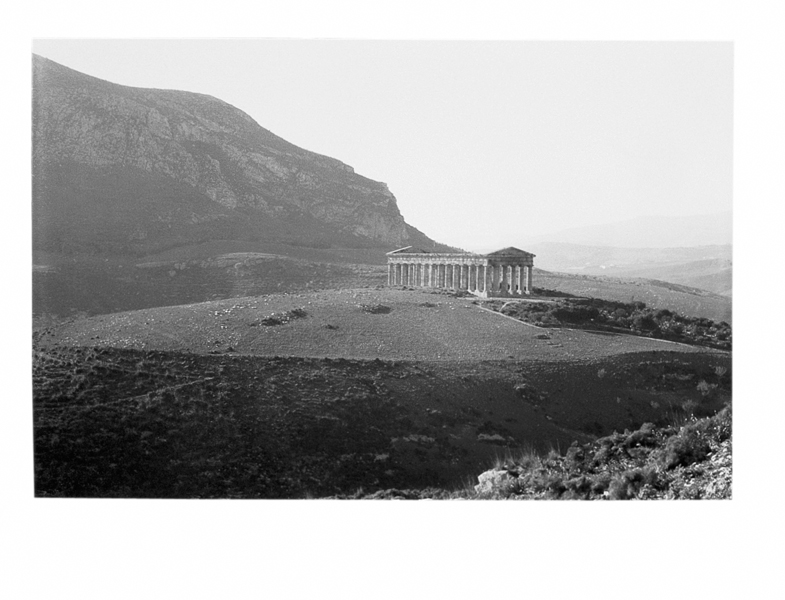

Even in his earliest photographs, which he shot as a teen – portraits of alleyways, façades, and streets – Melvin Charney, the Montreal-based architect-painter-photographer-intellectual, was examining the relationship between local and international vernacular architecture and daily life. As this show reveals, the buildings that we inhabit, and that inhabit us, as well as an entire system of visual representation are deeply linked to economic, social, and political forces. Charney’s richly evocative portraits zoom in on the dialectics of the everyday, work and play, industry and home, self and society, and, most significantly, building and body. In this retrospective of his photographic practice and its link to the public monuments for which he is best known, Charney shows us modernism’s influence on urban space, its historical roots, and its effects on our psyche. Using photographs from the mass media, poached from urban-development manuals and his own snapshots of urban architecture, he enters the debate over architecture and politics. His project is to question the built environment and the philosophy of the urban planner. From the beginning, Le Corbusier, father of modernist architecture, is evoked here. From Charney’s images of Montreal’s grain elevators, with their rational efficiency suited to the rhythm of factory work, to his photos of Tel Aviv’s modernist housing complex, White City, to his explosive Parable No. 9 . . . So be it: Factories are closing, museums are opening, in which workers’ bodies, dehumanized into “walking stiffs,” spill out into the museum, twisting on the floor and leaning on the wall, he fully realizes Le Corbusier’s mechanistic vision. “It is a question of building which is at the root of the social unrest of to-day: architecture or revolution?”1 Le Corbusier asked rhetorically, formulating his program to mould worker’s minds and bodies by uniting the Taylorism of the factory with domestic architecture. Charney’s visceral response to this philosophy of architecture as social control suggests that he is on the side of revolution, or at least of intelligent intervention; although he is not exclusively concerned with class, his show seeks to answer this question, drawing from but not bowing to other Promethean modernists – Malevich, Marinetti, Marx.

Exhibition curator Pierre Landry’s design, with its false walls between which viewers move in an orderly, disciplined way, draws attention to design as a force, as does his arrangement of the work, which eschews the obvious chronological order in favour of a medium-driven one, reflecting more accurately the layered narrative of Charney’s work. This forces the viewer to make connections between images and interpret the intellectually dense, sometimes impenetrable wall texts written by Charney himself, whose narration is like that of your favourite, most challenging professor: complex, dense, and worth the effort to decipher. Like a pictorial Talmud, the show reflects and folds back on itself, arguing with earlier versions, reusing, reinterpreting. Thus, it produces its own historical rhythms, and this is very much a part of Charney’s goal – to unwrap the architectural, urban, and visual past and bring it into the now, even into the very building in which we stand.

In his assembled photographs, in the “neutral” newswire photographs, and finally in his public monuments, layered in historical and social references, Charney reveals how the technologies of visuality, including photography, facilitate and make natural the destruction of the city. In his assembled photographs, the second part of the show, Charney presents triptych photos of buildings from various perspectives. This Duchamp-inspired technique of breaking the monocular fixed eye of linear perspective and its claim to unite viewers under a single visual – and a related ideological – system, investigates a new way of seeing old buildings, using the everyday image as a veritable philosopher’s stone. Not even nature is immune to the impact of culture, as he shows us in his large-scale photographic interpretation of trees in Rome’s Borghese Garden and in Versailles, here, it is the geometry of the photograph that constructs the mythic tree, transforming the organic into the geometric, nature into culture. Charney emphasizes the connection between the environment and social control in the accompanying wall text relating an allegory of how wayward boys, like the wild trees, were tamed and disciplined to conform.

In his prolific Un Dictionnaire, a compendium of newspaper articles and images that transform the everyday newspaper into a cultural signifier, Charney also links the visual to the linguistic. The blown-up newspaper pages collected over years reveal a visual grammar of the urban scene. By inserting his subjectivity with a gray slash of paint, Charney is able to manipulate the images that manipulate him. His goal of freezing the flow of images, thus disrupting the speed of the modern ideological machine, is most fully realized in his stories of urban development, his Parables. The “painted photographs” use the Un Dictionnaire images as a starting point to show the tenacity of the myth of global progress. These visual pop-up guides explode onto the page, invoking the history of Western architecture with sketches thickly painted directly on the visual plane of the newspaper, transforming culture into art, mass media into a theoretical text. The Suprematists, whose multiple repetitive geometric shapes and colourful masses are referenced, prefigured Charney’s passionate response to the built environment in their call for a new vocabulary of images in the post-revolutionary Soviet Union. Here, again, Charney masterfully and economically merges this aesthetic with photography’s crass realism, uniting the subjectivity of abstractionism, a specifically modernist response, with its enemy, the photograph. In doing this, he shows the ideological roots of both, exposing the hidden text, its historical roots and its predicted results. For instance, his twisted planes and monumental slabs come crashing down from above, a visual Tetris game, in which paintings are no longer abstractions but represent real buildings and real people. The photograph sets this process in motion; for instance, in Parable Series . . . Clenched Fists, Greased Palms, 1994, the vertical lines of the scaffolding of a new skyscraper visible in the newspaper photo burst onto the page in the painted overlay, laying over the bodies of the masses on bicycles. Here, the building is a weapon, violently dominating the people of the city. Thus, this layering exposes not only the history but also the formal strategy of the rationalized modern city.

The captains of development and their architects, hovering over their skyscraper landscapes, are the focal point of Charney’s concrete rage, which he reveals in blown-up images of Henry Ford Jr. in Detroit and I. M. Pei in Manhattan. Charney follows their plans to their final conclusion, where the line between building and person is blurred, as frightening skyscrapers come to life and grow legs as massive 3D sculptures that displace people, crush them, raze neighborhoods not only in North America, but also internationally, where modernization stamps its homogeneous grid. Bringing people into line is what the engineers of urban space do, Charney explains, culminating in this connection between these perambulatory buildings and us, walking through the museum, in the cultural institution that has borrowed its façade from the Montreal-based locomotive factory. With his explicit political message, his breathtaking overview of visual history, his relation to power, and his own architectural structures, where the public is invited not to run out of the city but, rather, to sit, think, and talk, Charney responds appropriately and hopefully to urban growth’s insatiable appetite. His wall-text comments are reproduced in the excellent book2 that accompanies the exhibition, as are the images from the show allowing viewers to continue to reflect on its themes and plumb its deepest layers.

2 Pierre Landry, Melvin Charney (Montreal, Musée d’art contemporain, 2002) with texts by Melvin Charney, and essays by David Harris and Gilles A. Tiberghien.

Danielle Schwartz is a writer and a doctoral candidate in the Department of Art History and Communications at McGill University. She is a member of McGill’s research team for the Culture of the Cities Project, and received, in 2001, a Fulbright award for a study of Montreal’s urban architecture. She can be reached at Schwartz@fulbrightweb.org.