[Fall 2009]

by Zoë Tousignant

The “problem,” or so it seems, is that Canada did not spawn photographic personalities on a par with those born, most notably, on American, European, or Russian soil. To put it bluntly, the Alfred Stieglitzes, László Moholy-Nagys, and Alexander Rodchenkos of this world – figures whose impact on the shape and character of the international history of modernist photography is undeniable – did not see the light of day here, nor did they visit much. According to the available literature, artistically minded Canadian photographers worked mainly within the institutional framework of camera clubs, which tended to promote a conservative view of the medium’s expressive potential.2 Whereas else where photographers were, by the 1920s and 1930s, embracing the creative possibilities of the new photographic technologies, Canadians continued to make images in the nineteenth-century pictorialist vein. Nevertheless, the aesthetic or style of photographic modernism was present in Canada in the realm of the mass-reproduced popular-culture photograph, and it can be discerned especially in the context of illustrated magazines.

As any good text on the history of twentieth-century photography will make clear, the relationship between modernism and the mass-reproduced photograph of the kind found in illustrated magazines was a close one. Thanks to a range of technological and socio-historical developments – including the invention and widespread implementation of the halftone and rotogravure printing processes, the professionalization of photojournalism, and the increasing sophistication of the practices of advertising and graphic design – the interwar period saw a boom in the industry of photographically illustrated magazines throughout the West. From the 1920s onward, photo-mechanically reproduced images became key players in the daily experience and representation of the modern world. Photographic artists working at this time collaborated in and reacted to the new phenomenon both by publishing their photographs in mass-circulation magazines and by drawing direct inspiration from (or appropriating) the images of popular culture.

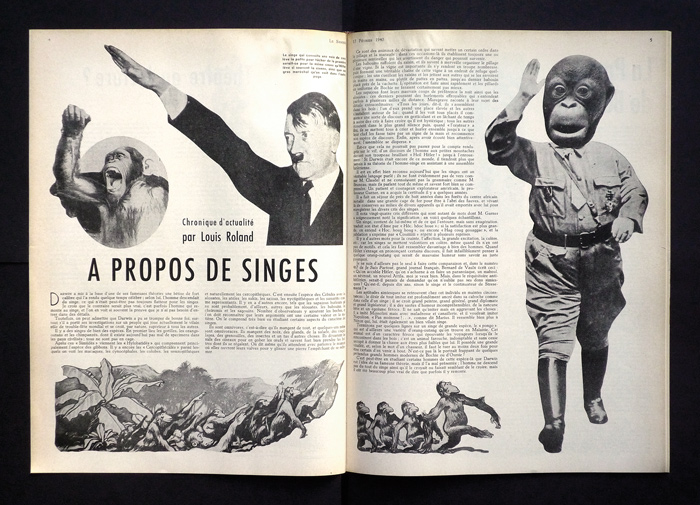

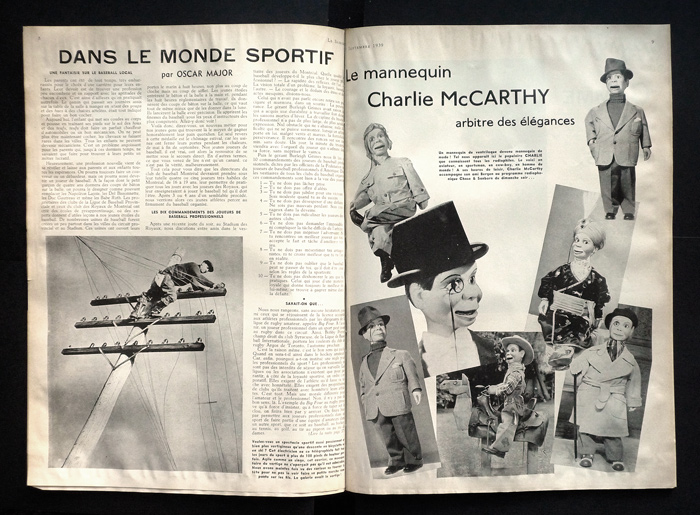

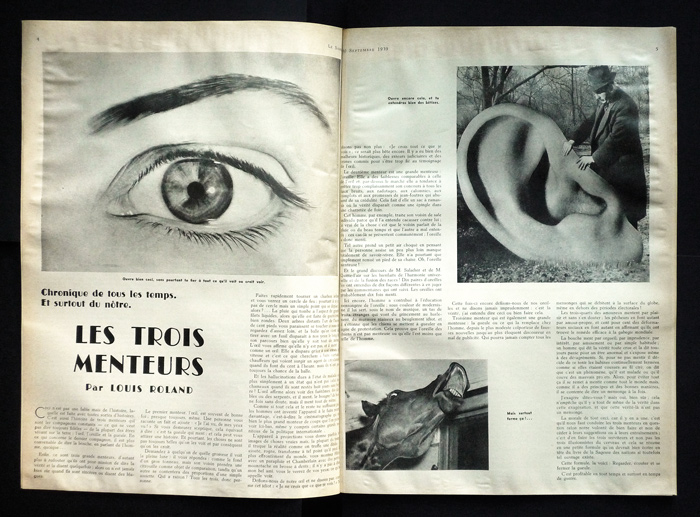

There were, in fact, so many crossovers between the works produced by modernist photographers and popular-culture photographs that one would be hard pressed, today, to assign the title of “original” to one and “copy” to the other. If not in intention, then at least in appearance, the images made by Charles Sheeler, Berenice Abbott, Walker Evans, Henri Cartier-Bresson, John Heartfield, Hannah Höch, and, of course, Stieglitz, Moholy-Nagy, and Rodchenko are strikingly similar to the throngs of frequently anonymous photographs reproduced during the same period in illustrated magazines. Certain themes and stylistic devices recur in both, chief among them the majestic grandeur of the modern city and industrial sites; the use of severe cropping and exaggerated angles to convey a sense of strangeness; the aesthetics of repetition, pattern, and fragmentation; and, most ubiquitously, the use of photomontage as an effective means of capturing modern life. Photographic modernism, in this sense, can be understood as a style that traversed the boundaries of “high” and “low” art in the non-hierarchical and fluid domain of “visual culture.”

Photomontage, the practice of cutting up and combining several photographs was effectively, the central mode of communication of illustrated magazines

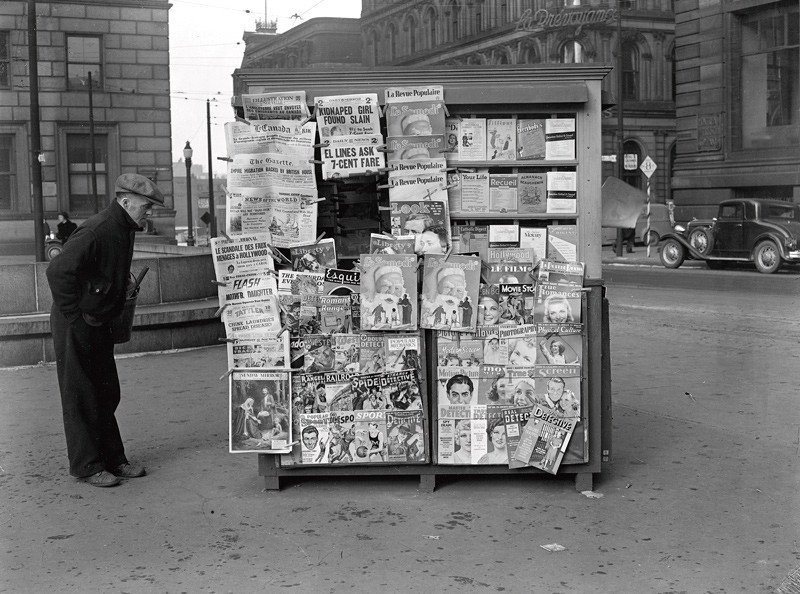

The mass-circulation magazines published in Canada in the 1930s and 1940s were not immune to this expanded movement of photographic modernism: such general-interest periodicals as Maclean’s, The Canadian Magazine, and Chatelaine – all three produced in Toronto and distributed across the country in the hundreds of thousands – were filled with photographs that make use of the themes and stylistic devices named above. The Francophone equivalents of these English-language magazines, which also abounded with photographs in the modernist style, included La Revue moderne, La Revue populaire, and Le Samedi. Published in Montreal, these were available all over Quebec and in other French-speaking areas of Canada and the United States.

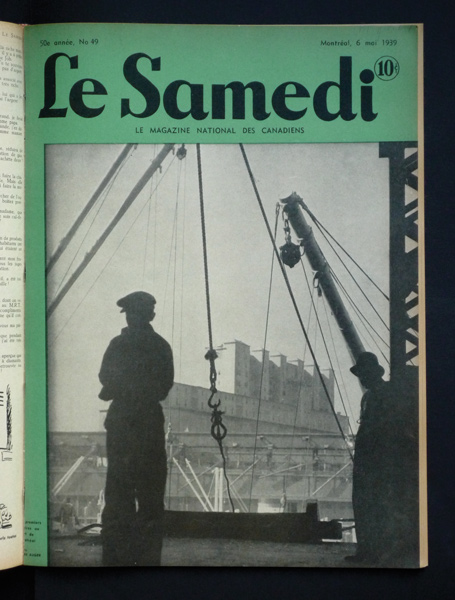

Poirier, Bessette & Cie, which produced Le Samedi, La Revue populaire, and Le Film, was at the forefront of Quebec’s illustrated-magazine industry and can thus be said to have been a central propagator of the popular-culture image in the province. Located in Montreal (on Le Royer, Craig, Saint-Jacques, Saint-Laurent, and de Bullion streets, successively), Poirier, Bessette & Cie was founded in 1884 as a printing and distribution company by Ferdinand Poirier and Joseph Bessette. Le Samedi, their first general-interest magazine, began in 1889 and was published on a weekly basis until 1963.3 After the death of Ferdinand Poirier in 1916, his sons Georges and Ferdinand Jr. took over the business and continued to publish both Le Samedi and La Revue populaire, a monthly that had been established in 1908 and whose content was slanted toward female readers. In 1919, they added to the list Le Film, a monthly devoted to current French and American films and film stars. In the late 1930s, a year’s subscription to all three magazines – amounting to seventy-six issues – could be obtained for only $5.00. The photographs that were reproduced in these three large-format, mass-circulation magazines were sourced both locally and internationally. Conrad Poirier, the reputedly eccentric Montreal-based photojournalist who worked for the newspapers La Patrie and The Gazette (among others), was the official photographer for Le Samedi and supplied images for many of the magazine’s covers and photo-stories.4 Other local photographers who contributed to Poirier, Bessette & Cie’s publications included Mark Auger, Henri Paul, and George Nakash (Yousuf Karsh’s uncle). Their photographs were reproduced alongside the multitude of pictures acquired from such Canadian and foreign organizations as Canadian Pacific, Air Canada, Associated Screen News, and Téléfrance. Although issuing from widely diverse agencies and locations, the images published in these magazines were cleverly mounted – or “reframed” – into coherent photographic layouts by the talented editorial staff.

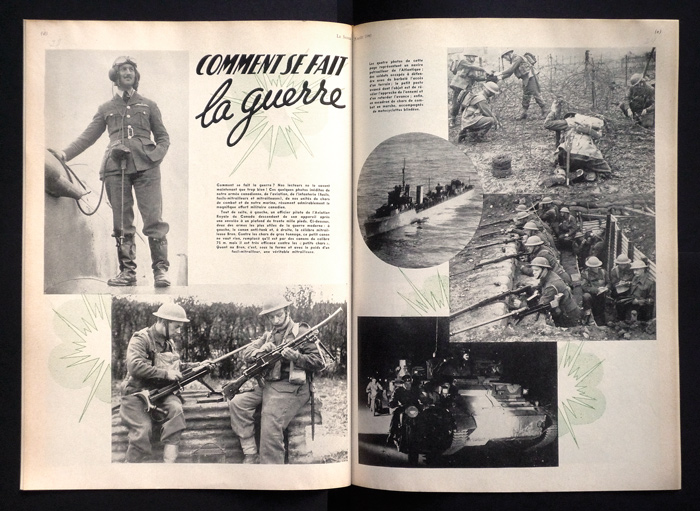

Photomontage, the practice of cutting up and combining several photographs into a new, graphically original composition that frequently includes other kinds of images as well as text, was, effectively, the central mode of communication of illustrated magazines like those published by Poirier, Bessette & Cie. The principal impetus behind this practice seems to have been the desire to look at and represent the world analytically – an atomistic impulse to break events down into their constituent parts in order to better understand or make sense of them. Numerous are the photomontages – in Le Samedi and La Revue populaire especially – that even take this analytical approach as a central theme. Whether representing the workings of the Canadian Army or the correct way to fasten a woman’s turban, such photographic spreads revealed the “making of” or “behind-the-scenes” of modern life; they disman- tled events and then reconstructed them, showing in the process how life works.

In what can be described as a brilliant act of self-consciousness, Le Samedi published such a photomontage in the issue celebrating the magazine’s fiftieth anniversary, released on June 17, 1939. Entitled “Comment se fabrique ‘Le Samedi,’” the four-page spread recounts each step involved in the making of an issue of the magazine. The photographs, taken by Conrad Poirier, show the company’s employees at their respective workstations, in the act of “producing.” As the accompanying text relates, the fabrication of Le Samedi was a team effort; starting with the editors’ initial creation of the mock-up and proceeding through the printing, cutting, and stapling of the magazine’s pages, the feature presents Le Samedi as the product of a rationalized, technologically advanced assembly line. Essentially a photomontage about the making of photomontages, “Comment se fabrique ‘Le Samedi’” is a self-promotional ode to industrial rationality intended to inspire admiration as much as to instruct.

The contribution of such publications as Le Samedi and La Revue populaire to the discourse of modernism in Quebec has been incisively demonstrated by Esther Trépanier in her groundbreaking book Peinture et modernité au Québec, 1919-1939.5 Her analyses of the critical texts by Jean Chauvin, for example, which appeared in La Revue populaire in the 1920s, have shown that the nature and purpose of art was very publicly debated within the pages of such periodicals, and thus that they were instrumental in the development and dissemination of the very idea of modern art in Quebec. But just as the discourse of modernism was being articulated by art critics in Quebec magazines, so, too, was the style of photographic modernism being played out therein, for all to see. Whether employed consciously or not, photographic modernism was the predominant visual language via which the experience and practice of modern everyday life was expressed.

3 Le Samedi was superseded in 1963 by Le Nouveau samedi, which was published in Montreal by Publications du Journal de Québec until 1981.

4 To date, only one text dedicated to Conrad Poirier has been published: a small exhibition leaflet co-produced by the Archives nationales du Québec, which holds the photographer’s extensive visual archive. See Le Montréal des années ’40: vu par Conrad Poirier, photographe (1913-1968) (Montreal: Ministère des affaires culturelles and Archives nationales du Québec, 1988). Poirier does, however, figure fairly prominently in Montréal au XXe siècle: regards de photographes (Montreal: Les Éditions del’Homme,1995), a publication edited by Michel Lessard.

5 Esther Trépanier, Peinture et modernité au Québec, 1919-1939 (Montreal: Éditions Nota bene, 1998).

Zoë Tousignant is a Ph.D. student in art history at Concordia University. Her doctoral research concerns photographic modernism in Canadian illustrated magazines between 1925 and 1945. She has published articles in Ciel variable and Archivaria, as well as contributing an essay on the photographs of Jules-Ernest Livernois to the exhibition catalogue Québec, une ville et ses artistes, produced by the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec in 2008.