[Fall 2011]

Victoria & Albert Museum, London, England

October 13, 2010 to February 20, 2011

“Shadow Catchers” takes off from the tradition of camera-less photography initiated by William Henry Fox-Talbot, whose photogenic drawings, first displayed to the public in 1839, preceded photography with a camera – a “little bit of magic realized,” as he put it. And we sense his influence on photographers who followed, such as Christian Schad, Lucia Moholy, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and Man Ray, whose photogenic drawings, schadographs, photograms, and rayograms played with forms, springs, mechanical objects, garbage, tickets, rags, and other objects on photographic paper. In “Shadow Catchers,” an ingenious array of contemporary responses to this environmentally sensitive medium, we learn about photographers who are extending the range of possibilities and subjects available to camera-less photography.

Floris Neusüss is a romantic of sorts, who studied mural painting before turning to camera-less photography in 1954. Best known for his Korperfotogramms (full-body photograms on silver-bromide and autoreversal paper) of the 1960s and 1970s, which are on view in “Shadow Catchers,” Neusüss has extended his practice to include shadowy metaphorical images of couples on photographic paper. Ephemeral, evanescent bodies become a dialogue on life and death. In the image of a woman in fetal position in Untitled (Korperfotogramm, Kassell, 1967), what touches the photo-graphic paper is clear and sharp, while other bodily outlines and features are blurred, creating a surreal, otherworldly effect. There is something of performance art in Neusüss’s approach. He even produced a life-size photowork revisiting Lacock Abbey to capture the lattice window that inspired Fox Talbot’s 1835 photogenic drawing.

Nature comes through in ways that most photographers would never conceive of. As Neusüss comments, “In the photogram . . . man is not depicted, but the picture of him comes into being by an act of imagination.” Fabian Miller works on the margins of photograph, finding his own visual path with a reverence for nature. Although the geometrics of Miller’s compositions seems akin to Wassily Kandinsky’s or Bruno Munari’s, the circle and square motifs, for Miller, represent nature and thought, respectively. The sense is of a transitory space, an emergent form; these photographs are places you go into, and their very simplicity is striking and brings a focal strength to them. Not everyone will like Miller’s photographs because they are so esoteric, symbolically trapped, and removed from straight photography. A kind of process photography or intensive fieldwork study, Miller’s Year One (2005–06) and Year Two (2007–08) involved creating a camera-less photo each day for a year, then selecting the best. Ninety-nine from this project became the book Year One.

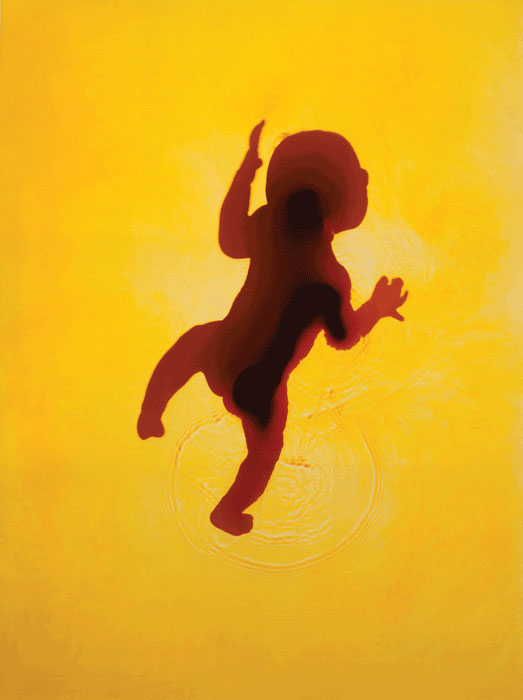

Susan Derges is very much aware of the staging aspect of camera-less photography. Living close to nature in County Devon, Derges makes works that walk the line between invisible forces and the visible manifestations of life that are part of her everyday environment. Witnessing spawn on a pan, and its reflections in the lower depths of water, Derges effectively recognized this phenomenon as a photographic print made by the sun. Water became a key to everything in Derges’s photography. Her early pieces reference birth – the forming and beginning of things – while her more recent pieces focus on the dissolution, loss, or reconfiguration of elements of nature, and their complex interweaving of energies make for a very interesting, somewhat romantic approach to art. One considers Wordsworth and the Romantics, as much as contemporary photography, a potential reference point for Derges’s art. She notes, “When I made the final photogram, I floated all the layers of material in water – so you get a little distortion, some cusping round the seed-heads. This gives a slightly ambiguous, magical quality to the image. The arch-shaped frame was inspired by Italian frescoes I saw in Siena; in my mind, it suggests a portal to another world. It also evokes the state of reverie and imagination that is triggered by the Dartmoor field. That, for me, is as important as the place itself. I wanted to evoke the feeling of lying down low in grass – a child’s perspective, or an animal’s.” We feel our place in the process of nature, as if we ourselves are invisible observers witness to change, entropic processes, captured by light on paper.

Pierre Cordier, aka Mr. Chemigram, is anti-nature and pure art. While in military service in Germany, Cordier experimented with making his first chemigram, using nail varnish, to create a photograph celebrating the twenty-first birthday of a young German woman named Erika. The varnish caused a chemical reaction in the developer. Brassai wrote to Cordier in 1974 about how anti-photography his process was, stating, “The result of your process is diabolical – and very beautiful. Whatever you do – don’t divulge it!” Cordier’s quasi-scientific approach caused him to refer to himself as a faux-tograph, but the alchemical aspect is comparable to the “chemical naturalism” of German painters Sigmar Polke and Anselm Kiefer. The magic is uncontrolled, and the results are often surprising for their hypothetical geometries and patternings, often featuring light/colour grids.

The best known of all camera-less photographers, Adam Fuss was attracted to application of the photogram outdoors. The world of nature becomes a theatre of life, expanding our place in the cosmos in a way that the traditional photographic image, even if it is Photoshopped, cannot. The camera-less photograph becomes a metaphorical valley into which we step, just as Fuss has, never to return to standard photography. Fuss sees his art as a potential link to experiential tensions and as an endless transition, an invisible world that is revealed through the processes involved. Snakes and Ladders, a project that has recently absorbed him, plays with the biblical snake metaphor and its associations with evil. Fuss’s image of the snake, both beau-tiful and threatening as it moves through water, captures motion with great eloquence, and the physics of the camera-less approach sensitively links the subject to the environment. The power of the mythology and the real life of snakes fuse into a photowork that involves a chance element. Even as these photoworks are meditations on our spiritual links to recurring ancient motifs, they are also recordings of a living and enigmatic moment in time.

While new technologies are redefining the content and process of imagery in twenty-first-century society, camera-less photography follows another path that involves interactivity just as new technologies do, but with nature and the physics of the world we are a part of, in a low-tech way. The site-specific light-gathering processes involved in camera-less photography lib-erate the photographer by forging a reconnection with the world around him or her in a very direct way. “Shadow Catchers” brings together a rare assortment of camera-less photographers whose sensitivity to the forces of nature, to the forces of physics, and to light and shadow on paper extends the language of photography back to its point of origin. Nature co-produces the imagery, and therein lies the magic!

John K. Grande is the author of Art Nature Dialogues: Interviews with Environmental Artists (State University of New York Press, 2007), and Dialogues in Diversity: Art from Marginal to Mainstream (Pari Publishing, 2008). He is co-author of Natura Humana; Bob Verschueren (Editions Mardaga, 2010) and Le Mouvement Intuitif: Patrick Dougherty and Adrian Maryniak (Atelier Muzeum 340, 2005), and co-curator of Eco-Art with Peter Selz at the Pori Art Museum (2011) in Finland. Soon to be released is Homage to Jean-Paul Riopelle Gaspereau/ Prospect 2011). grandescritique.com