[Printemps/été 2012]

by Robert Evans

David Askevold’s work is variously labelled as post-minimal, conceptual, narrative, story art, and post-movement, although none of these is adequate. Westerns, country-and-western music, poltergeists, ghosts, spirits, games, rules, narratives, dreams, history, geography, scientific imaging, and anthropology all inform his work. The list of materials and approaches with which he worked is similarly eclectic: photographs, drawings, diagrams, sculptures, snakes, texts, videos, films, fires, chocolates, and performance. As a result, as proved by the recent posthumous touring retrospective of Askevold’s work organized by the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, any extensive survey of his corpus must be equally eclectic and disorienting.

Askevold’s early career is closely associated with the so-called golden age of conceptual art at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in the 1970s. His “Projects Class” course was an important component in establishing NSCAD’s reputation as one of the “hot” art schools of the period, and his students collaborated on projects with such now-recognized artists as Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, Dan Graham, and Lawrence Weiner. Askevold’s Fill (1970) is a straight forward conceptual art video performance from this period. The artist set up a static camera and then “filled” the frame of the video by wrapping layers of aluminum foil around a centrally placed microphone. The execution follows a procedure implied by the title of the work, and there are no surprises in the narrative. The screen fills with foil, and then the screen empties of foil. The execution yields interesting forms – both visual and audio – as light reflects off the texture of the foil and the microphone records the surprisingly distinct sounds of its being covered and then uncovered.

Askevold’s photo-text work of the same period also conforms to our expectations of 1970s conceptual art; Taming Expansion (1971) is a typical combination of photography, diagrams, and san-serif text.1 The narrative involves a determined group of art students in New Mexico videotaping their attempt to corral rattlesnakes within a circular area with twigs and branches – literally, to “tame expansion.” However, according to the text, one of the students was bitten by a snake and taken to the hospital, the video equipment was accidentally destroyed, and the snakes were corralled into a bag before the piece could be completed. The resulting artwork – a lithograph combining a photograph of a small-town street in New Mexico, the textual narrative, and a line diagram that graphically represents six coiled snakes confined within the centre of a larger circle – suggests the event; however, despite the presence of the indexical photograph, there is no evidence that the event took place.2 The symbiotic authority created by the juxtaposition of photograph and text provides a “document” or “proof” of the fantastical situation and nonsensical proposition.

The ostensible authority of the photographic index also extends to film and video in Askevold’s work. Nova Scotia Fires, a colour film from 1969, is a haunting mix of explosive colour, natural beauty, and ambiguous audio. Askevold poured gasoline on rocks along the south shore of Nova Scotia, set the fuel alight, and then filmed the result. The work can be explained through appeal to the rationale of a conceptual artist: pour gasoline on rocks, set on fire, observe results. However, the post-production addition of the distinct grumbling and buzzing audio track and the constantly changing camera angles and framing betray Askevold’s interest in film as more than a means to record the outcome of an executed idea. It is a disturbingly beautiful film, one that both entices and repels as the viewer is presented with an impossibility – flames erupting from a rocky shoreline – recorded on film.

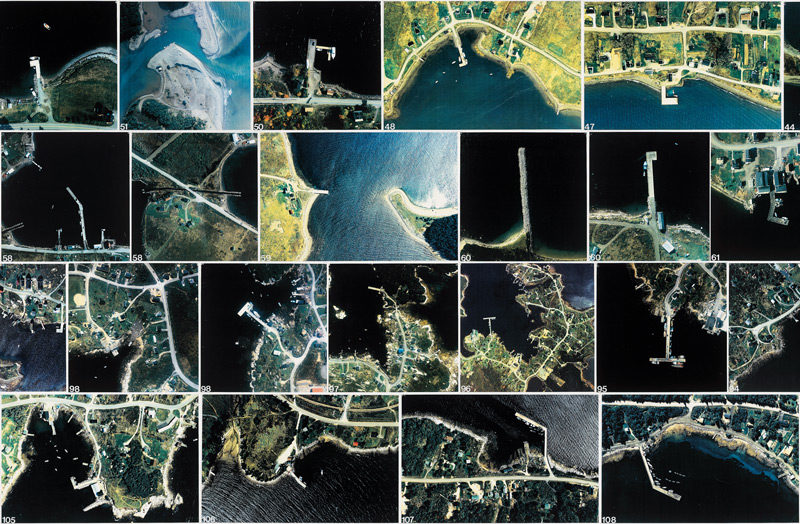

Despite its geographical connection, The Nova Scotia Project (1993–95) is as distant from Nova Scotia Fires as imaginable. The main component of the project, Once Upon a Time in the East (1993), is a grid composed of orthogonal aerial photographs, acquired from the Department of Fisheries and Ocean, of small-craft harbours. The grid is flanked by two videos. The first is an underwater video, supplied by Fisheries and Oceans, of fish entering the mouth of a dragger net. The second is an oblique aerial view of the coastline of Nova Scotia narrated by a geologist from the Bedford Institute of Oceanography. The Road Journal (1994–95), another component of the project, provides a worm’s-eye view of highways in coastal Nova Scotia, and End of the Road Matrix (1994–95) is a collection of architectural views along those same roads. The final part, Don’t Eat Crow (1994), is a video of crows scavenging for food as a narrator reads letters that tell a story of financial hardship. The synthesis of these disparate views in the context of the Atlantic fisheries crisis in the 1990s suggests a political work that is about the struggle of small fishing communities to survive; however, it is never made explicit.

The visual components of The Nova Scotia Project, with the exception of Don’t Eat Crow, are documentary in the strictest sense of the word. The aerial photographs in the grid were purchased from an institutional source. Road Journal uses a repetitive, neutral approach to its subject matter – each photograph was taken by placing the camera on a brick in the middle of a road. The narration in the coastal aerial views video is matter-of-fact, conveying empirical facts and observations regarding the land below. And the dragger net video was shot by a remote camera from a fixed location. Yet, the piece is not didactic. Each “fact” on its own is comprehensible, but the viewer struggles to make sense – to construct a narrative, to come to a conclusion – from this embarrassment of information. Thus, there is a sense of disorientation when viewing The Nova Scotia Project despite the legibility of its components.

In much of Askevold’s work there is a similar deployment of rational elements to irrational ends resulting in a façade of legibility, typical of conceptual art in the 1960s and 1970s. But often, even the “rational” elements are suspect. Askevold’s colleague and former student Mike Kelly notes that the artist seemed to be more concerned with the “poetics of the pseudosciences, such as pop psychology and the occult,”3 leaving the structure of the works – the grid, the sequence, the geographical specificity – to convey the conceit of legibility. Indeed, for Askevold’s masterful combination of pseudo-facts and structures, Kelly labels him a “disorientation scientist.”4

Askevold’s career began during the heyday of the various “isms” of the 1960s that re-established narrative in art, and he continued to work with narratives throughout his career.

Love Mansion (1997), like The Nova Scotia Project, is a place-specific work, but this time it is a single house in Santa Monica, California, that was built for the silent-film star Norma Talmadge and subsequently occupied by numerous celebrities, ranging from Grace Kelly to Roman Polanski. Askevold combines a seemingly didactic panel, comprising a postcard of the house and explanatory text, with a grid of nine prints that includes a dissolving game of tic-tac-toe, a shimmering game of dice, and haunting obscured domestic views. The glowing saturated colours in the prints are otherworldly and hint that the didactic panel does not tell us the whole story, but the colourful grid does not substantively expand our understanding of the site.

The super-saturated colours in Halifax Ghosts (1999) are not as seductive as the glowing forms in Love Mansion. Each “picture” consists of an artificially coloured three-dimensional sea- floor map onto which Askevold has added photographic night views of Halifax and a variety of images and clip art. The elements scattered about the harbour floor create a subaqueous realm of devils, skeletons, shipwrecks, mythical creatures, wrecked cars, and free-floating text. It’s an ambiguous but engaging space, hinting at a profound history of the harbour’s depths without offering a historical narrative.

Two Hanks (2003) is Askevold’s Gesamtkunstwerk of disorientation. Askevold performed the piece, originally an illustration of a concept in the late 1970s,5 for video in front of an audience in 2003. Part séance and part performance, the ambiguous outcome of detailed planning and organization, it fails to reach the spirits of the “two Hanks” – country-music stars Hank Williams and Hank Snow – although it gives us a rich and eclectic visual spectacle. Fog falling from suspended blocks of dry ice drifts through a darkened room while music by the “two Hanks” plays, calling to them in the beyond. The audience members stare blankly in the dark and are revealed in the eerie green glow of night-vision video, becoming phantasmagoric participants, halfway between us and the anticipated “Hanks.” A wailing theremin and Askevold’s percussive bass collide with the country music on the audio track, adding another level of complexity and disorientation. The séance fails; the “Hanks” never appear. At the end of the video, the audience is relieved of the otherworldly atmosphere when the room lights come up, the audience applauds the performance and the performers, and the “disorientation scientist” acknowledges his success to the crowd.

Askevold’s career began during the heyday of the various “isms” of the 1960s that re-established narrative in art, and he continued to work with narratives throughout his career. While the full scope of his work between the late 1960s and his death in 2008, in terms of both subject matter and media, has been only hinted at here, it is obvious that Askevold routinely played with narrative, overlapping and juxtaposing congruous and incongruous elements often to a single effect: a rich, albeit often disorienting, ambiguity.

2 Torres and Askevold, “The Language and the Object,” p. 88.

3 Mike Kelly, “In the Weave of Reason: Tony Oursler and Mike Kelly on David Askevold (1940–2008),” ArtForum International vol. 46, no. 10 (2008): 70.

4 Kelly, “In the Weave of Reason,” p. 70.

5 The Ghost of Hank Williams, 1977–80.

Robert Evans is an independent scholar and visual arts consultant. He holds a Ph.D. from Carleton University and received a BFA from NSCAD in the late 1980s. His current research interest is nineteenth-century landscapes of loss.