[Spring/summer 2012]

Jacky Georges Lafargue and Louis Couturier’s project Resolute Bay – Voyage du jour dans la nuit finds a way to take viewers on a sort of voyage to the far reaches of our country and an encounter with people who live in a remote Inuit village with only about two hundred inhabitants. What is so interesting about these frigid, arid spaces and these communities, in which survival is still the top priority? Why the infatuation with the Far North these days?

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit / Journey of a Day into the Night, 2006, images tirées de la vidéo / images from video, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit / Journey of a Day into the Night, 2006, images tirées de la vidéo / images from video, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

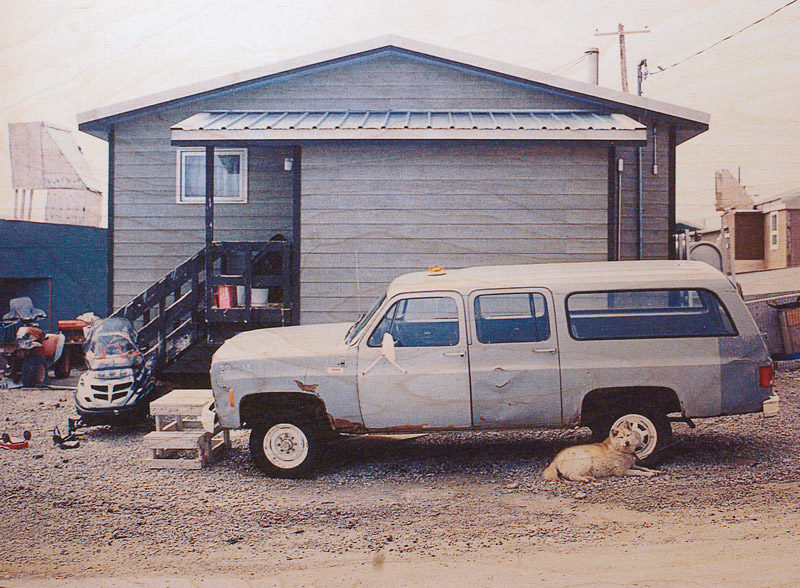

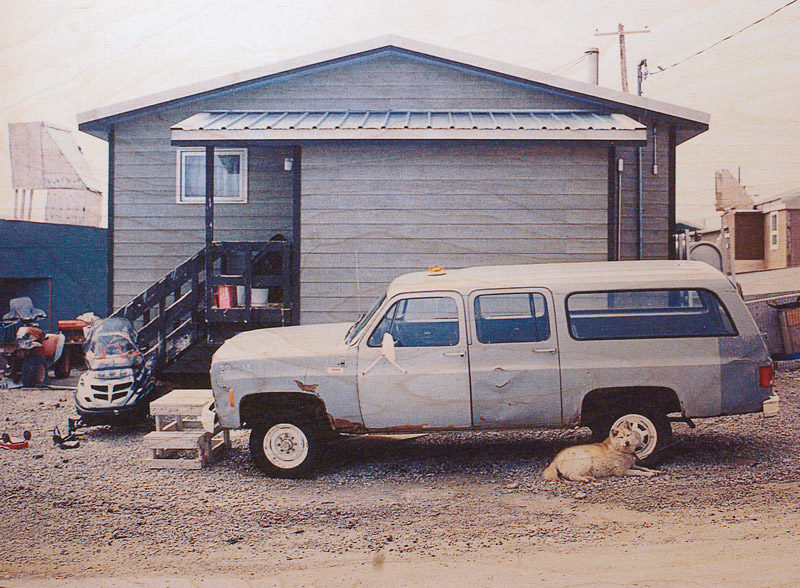

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Sans titre / Untitled, 2011, impressions jet d’encre

sur contreplaqué de bouleau blanc ou sur plexi

pour boîte lumineuse / inkjet prints on white birch plywood or on plexi for backlight, 44 x 60 cm,

permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Sans titre / Untitled, 2011, impressions jet d’encre

sur contreplaqué de bouleau blanc ou sur plexi

pour boîte lumineuse / inkjet prints on white birch plywood or on plexi for backlight, 44 x 60 cm,

permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Sans titre / Untitled, 2011, impressions jet d’encre

sur contreplaqué de bouleau blanc ou sur plexi

pour boîte lumineuse / inkjet prints on white birch plywood or on plexi for backlight, 44 x 60 cm,

permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Sans titre / Untitled, 2011, impressions jet d’encre

sur contreplaqué de bouleau blanc ou sur plexi

pour boîte lumineuse / inkjet prints on white birch plywood or on plexi for backlight, 44 x 60 cm,

permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Sans titre / Untitled, 2011, impressions jet d’encre

sur contreplaqué de bouleau blanc ou sur plexi

pour boîte lumineuse / inkjet prints on white birch plywood or on plexi for backlight, 44 x 60 cm,

permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Sans titre / Untitled, 2011, impressions jet d’encre

sur contreplaqué de bouleau blanc ou sur plexi

pour boîte lumineuse / inkjet prints on white birch plywood or on plexi for backlight, 44 x 60 cm,

permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Sans titre / Untitled, 2011, impressions jet d’encre

sur contreplaqué de bouleau blanc ou sur plexi

pour boîte lumineuse / inkjet prints on white birch plywood or on plexi for backlight, 44 x 60 cm,

permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Sans titre / Untitled, 2011, impressions jet d’encre

sur contreplaqué de bouleau blanc ou sur plexi

pour boîte lumineuse / inkjet prints on white birch plywood or on plexi for backlight, 44 x 60 cm,

permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

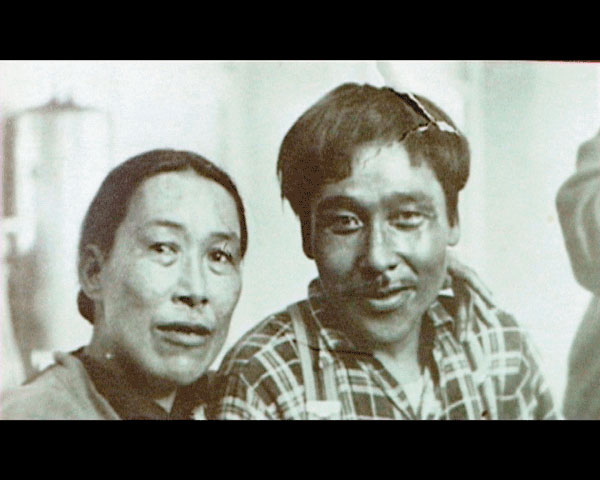

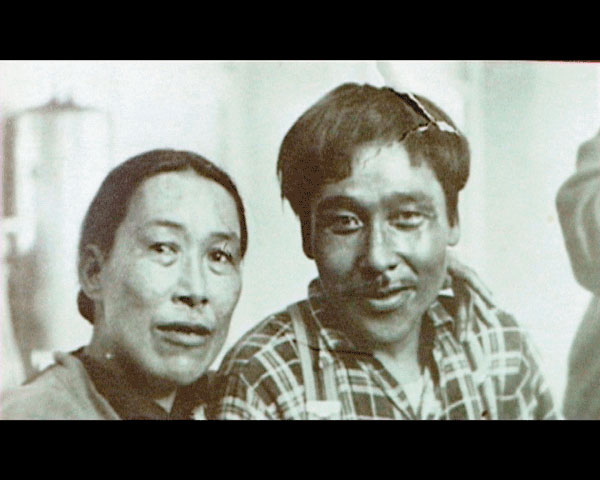

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

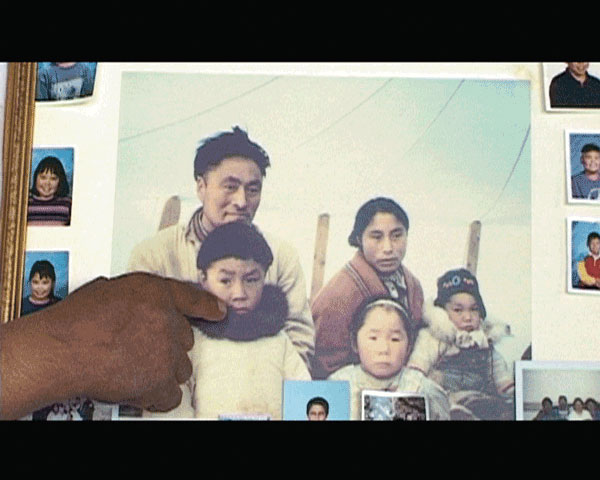

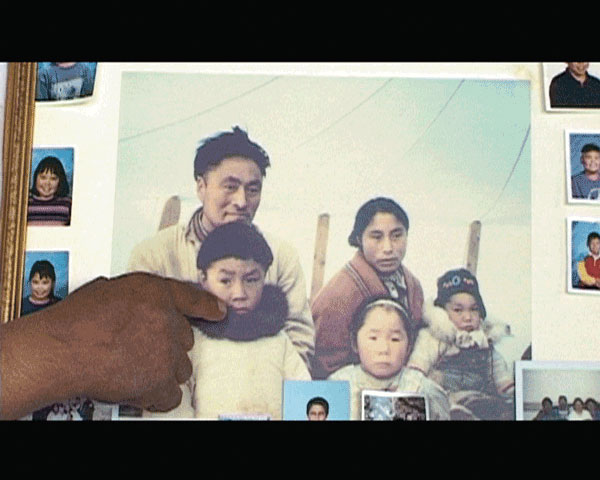

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

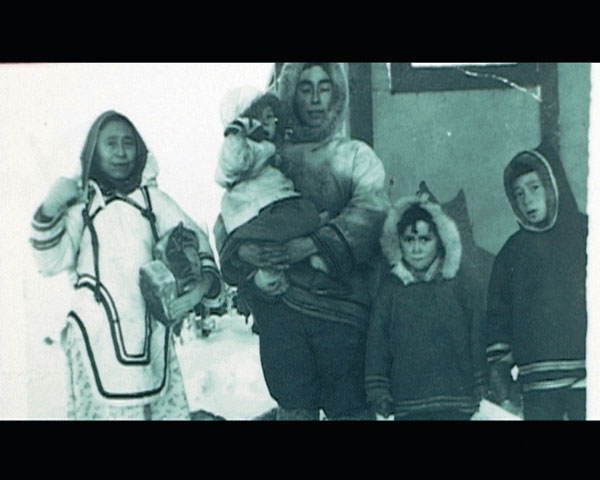

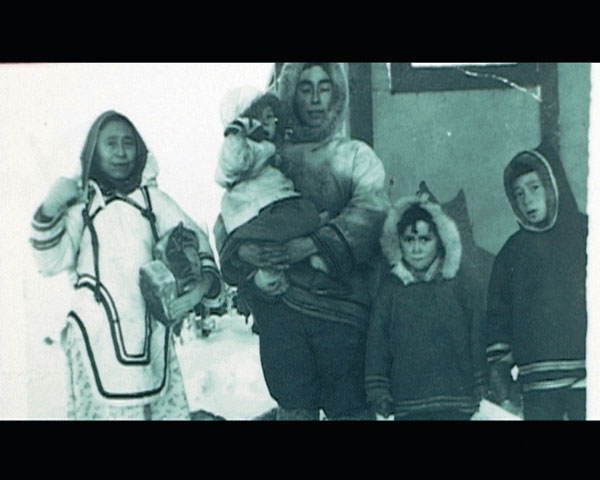

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Le voyage du jour dans la nuit et Resolute Bay /

Journey of a Day into the Night and Resolute Bay,

2006, images tirées des vidéos / images from videos, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Voyage du jour dans la nuit / Journey of a Day into the Night, 2006, image tirée de la vidéo / image from video, permission de / courtesy of Centre SAGAMIE. © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier, Qausuittuq, « un lieu sans aube » (version no. 2) / Qausuittuq, “place with no dawn” (version no. 2), 2011, installation (traîneau chargé de 24 caisses contenant des images de resolute Bay / sled loaded with 24 crates containing images of resolute Bay). © Jacky George Lafargue & Louis Couturier

Since the Centre for Northern Studies (cen) was founded by Louis-Edmond Hamelin, today considered the father of Canadian northern studies, at Université Laval in Quebec City in 1961, the discipline has changed and developed a great deal. The northern studies scientific community has been consulted extensively since the Plan Nord was instigated by Jean Charest’s government in Quebec and has helped to broaden public knowledge about the details of this immense territory and its inhabitants, although much research remains to be conducted on social development in the North. Over more than a decade, a fascination with the North has also been manifested on the cultural level, as evidenced by the many works of music, literature, film and video, multimedia, and visual art devoted to the subject.2 Such diversity in artistic disciplines encourages interest in northern culture.

People who live in the North, however, have been confronted with numerous upheavals. Major socio-economic and cultural changes are currently underway in Northern communities, but the question of identity remains central. Of course, the North is of obvious significance because of the strategic stakes in maritime access and passage and because of its prospect as a shimmering Eldorado; nevertheless, our true attraction to it seems to transcend the material.The installation presented at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts consisted of two videos simultaneously projected on wall-mounted monitors and a sculpture installed in the centre of the gallery. The first video, with a documentary aesthetic, introduces the inhabitants of Resolute Bay, an Inuit village in far northern Alberta, whom Lafargue and Couturier encountered in March 2006.3 These people relate the origins and history of their move to Resolute Bay. One of the first men to have been forcibly moved there, in 1953, tells us that the village was created by the government of the time as a way to assert Canadian sovereignty over the islands of the High Arctic. Members of the older generations speak about the difficult conditions to which they had to adapt when they arrived in Resolute Bay from Inukjuak or Pond Inlet, and about the promises that were made to them about the abundance of animals in the area and the possibility of returning to their homes after two years. These promises were not kept; the only concession made to them was to have the rest of their family members come to join them.

People who live in the North, however, have been confronted with numerous upheavals. Major socio-economic and cultural changes are currently underway in Northern communities, but the question of identity remains central.

In this isolated, barren region, where the temperature dropped to –50°C in the winter, they had to live in tents until houses were built. Yet, today, they seem resigned to their fate and say that they like the village, where they can travel, camp, hunt, and fish in the twenty-four-hour daylight in summertime. The younger generation, who were born in Resolute Bay, are more optimistic, even though they are bound up in the tragedy of alcoholism, drug addiction, and other problems linked in part to their resentment toward the government.

The second video, in a freer style, sums up the artists’ stay in the community and their encounters with the inhabitants. It shows the rudimentary housing and daily life in the village and the reaction to the screening of the images in this video, which portrayed them. The videos were projected onto a screen made of snow that was designed by the artists and erected in the public square of Resolute Bay in March 2006. We see an epiphanic performance in which happy children react enthusiastically, recognizing themselves on screen as if they were appearing by magic. These images, with their drop-shadow, offer a true spectacle in which, to borrow from a Jacques Rancière title, we can glimpse the “emancipated” spectator.” “Some use subtle explanations or spectacular installations to show the blind what they do not see,” Rancière writes. “Others cut out the evil at the root by transforming the spectacle into action and the spectator into an active human being.”4 Beyond a vision, Lafargue and Couturier allow us to experience and imagine a sort of theatre within a very empathetic theatre. This screening expresses the tone of both the project as a whole and its creative process. That is, the work underlying these videos is linked to the “attitude” of the artists, for whom participation and collaboration were important components of the artwork. They became engaged with the community and didn’t take a specific position or dominate the situation or the circumstances in the relationships that they forged. This is their gift to that community. This admirable attitude testifies to a desire to bring art into life.

The sculpture in the centre of the gallery is emblematic of the work as a whole and offers a metaphor that allows the semantics of the installation to be deciphered. It consists of a sled that comes from Inukjuak, “just like the first inhabitants of Resolute Bay,” according to the artists, who also tell us that it belonged to the author of the book The Harpoon of the Hunter, Markoosie Patsauq. Placed on the sled are eighty plywood light boxes containing images of the houses in Resolute Bay (or Qausuittuq, its name in Inuktitut). This hybrid sculpture evokes not only the presence of the Far North but, through its original function, transports us to the heart of the village. In addition to showing us this means of transportation and tool for hunting, Lafargue and Couturier reach out to the remote countryside and make it somehow a part of their expedition. “The power shared by spectators is not related to their quality as members of a collective body or a specific form of interactivity.

It is the power that each person has to translate in his or her own way what he or she perceives, to relate it to the unique intellectual adventure that makes each similar to all others even though this adventure is not similar to any other.”5 Resolute Bay offered such a rendez-vous, a strong encounter that also leaves us “emancipated.”

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 The exhibition was in Montreal from 6 November 2011 to 8 April 2012. Two other components of the project were also presented at the Moose Jaw Museum and Art Gallery in Saskatchewan and the Musée de Picardie in Amiens, France. All three components of the installation can be found on the Web site of the latter institution (resolute-in- museum.net/fr/). The project is also fully documented in the beautiful and generously illustrated book Resolute Bay – Voyage du jour dans la nuit (Alma: sagamie édition d’art, 2011).

2 Among others, exhibitions produced in Montreal presenting works from the Inuit art community include at La Centrale/Powerhouse (“Ciel ecchymose” curated by Stéphanie Chabot as part of the “Femmes de l’Arctique” series) and the McCord Museum (“Inuit Modern,” the Samuel and Esther Sarick collection from the Art Gallery of Ontario, curated by Gerald McMaster and Ingo Hessel). Several Quebec magazines have also published instructive articles on northern studies, including Liberté (No. 262, “Nord, création et utopie”), Spirale (No. 225, “Phénomènes contemporains de la culture inuite”), and Cap-aux-Diamants (No. 108, “Le Québec: Nord et nordicité”). Éditions J’ai VU published Nordicité under its “l’opposite” imprint (Quebec City, 2010). Finally, the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec recently began to offer a research and creativity residency for artists and writers in Inkjuak and Kanqiqsujuaq in Nunavut.

3 The dialogue and list of names are given in the Resolute Bay – Voyage du jour dans la nuit (Alma: sagamie édition d’art, 2011) on pp. 69–73.

4 Jacques Rancière, Le spectateur émancipé (Paris:

La fabrique éditions, 2008) (our translation).

5 Ibid., p. 23 (our translation).

From 1991 to 2008, Jacky Georges Lafargue and Louis Couturier worked together under the name Attitude d’artistes. Their creative process began with the use of a participatory strategy that made art of encounters. This engagement resulted in numerous projects produced in different places and communities. Photography is their main component, showing the different steps in creation of works in the public space. In addition to Resolute Bay, these works include Une île à la mer (2004) and Road Island (2002–03), projects that bring together social intervention and exchange as creative process. www.resolute-in-museum.net

Sonia Pelletier is the publishing coordinator of the magazine Ciel variable.

This text is reproduced with the author’s permission. © Sonia Pelletier

Purchase this article