[Winter 2012]

Berenice Abbott: Photographs

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

23 May to 19 August 2012

Toronto, being such an architectural and photographic city, seems the perfect venue for a Berenice Abbott show. In collaboration with the Jeu de Paume in Paris, Toronto’s Ryerson Image Centre mounted a fine, comprehensive survey exhibition of Abbott’s life in photography. Early on, Abbott got to know Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray in Greenwich Village, New York, before heading for Paris to become Man Ray’s apprentice and assistant. (There is a portrait of Abbott by Man Ray from 1925 in the show.) The Paris period was marked by portrait studies that are not environmental but focus on the faces and expressions of each subject. There are few props or devices in these early photographs, in contrast to those by portrait photographers such as Arnold Newman and Yousuf Karsh. We see Jean Cocteau in 1927 swathed in white sheets and holding a surreal-looking, crash test dummy-like plaster head, and Marie Laurencin engaging with Abbott’s camera straight on. Princess Eugenie Murat (1926) looks very butch and authoritative, whereas the writer Djuna Barnes (1926), who called herself the “unknown legend of American literature,” is the epitome of elegance. And, of course, there are the often-seen photographs of James Joyce, in one of which he is wearing his eye patch. André Gide looks very much like a thoughtful François Mitterrand. Also included is a 1927 portrait of the ageing photographer Eugène Atget, a seminal influence on Abbott, who was instrumental in saving his largely forgotten prints and photographic glass plates. In 1928, she purchased several thousand of them from André Calmattes. She went on to restore Atget’s status as a photographer by sending his prints to shows, even facilitating the publication of the book Atget Photographe de Paris (1930).

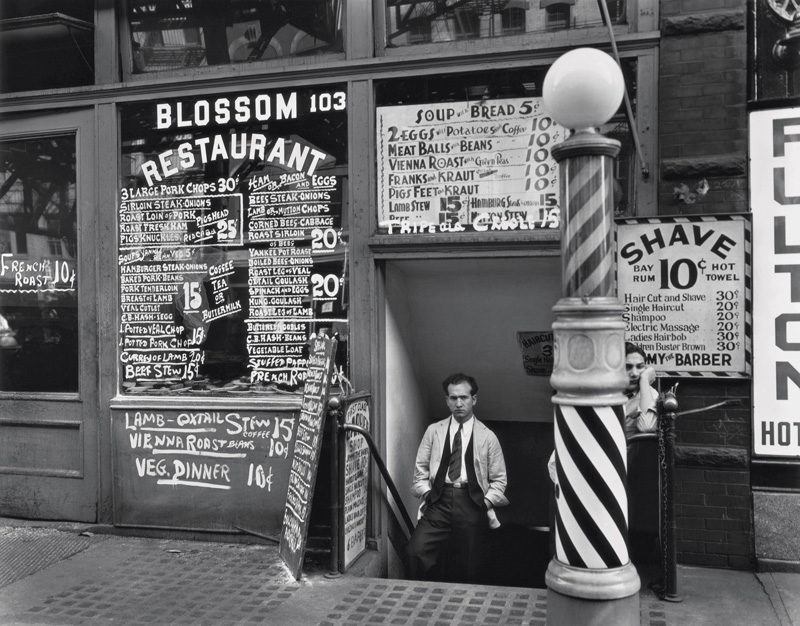

The AGO exhibition includes a large selection from Abbott’s Changing New York City project, which she began after returning to New York. This is snapshot anthropology at its best! The New York scrapbooks (1928–30), all on view in the vitrines in the AGO’s darkened interior show space, were the fuel for Abbott’s Changing New York City series. Shots of Chinatown and Manhattan are pure exploration of urban space, architecture, and the movement of people in the city. From chop suey restaurants, to rooftops, to skyscrapers, to elegant ironwork bridges, to food markets, to the homeless, workers, and boats on the waterfront, Abbott covered the less-covered territory of New York with her straight and searching style. The never-before-exhibited personal documents – letters, book mock-ups, drawings, magazines, scrapbooks, first-edition books, and notes on New York City – are a life-sized study in motion, place, and context, all done with great sensitivity to the conditions of light, and in how Abbott thought and worked. Changing New York (1935–39) is the core of this show, an unself-conscious parade of people and scenes, amid commerce and the urban scene, presented almost as if New York were an experiment in futurism. Before Abbott undertook the project, she toured Europe with the scholar, architectural historian, and critic Henry Russell Hitchcock investigating and documenting Victorian buildings, and she studied such classic forerunners of modernism as Henry Hobson Richardson in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia.

Changing New York is proto-photo America. All black and white, it paves the highways and plazas for Robert Frank’s and Lee Friedlander’s post-war America. A shot of a gun-shop sign pointing menacingly at the street, a photomontage of New York’s bridges, workers, landscape and buildings – it all speaks for an idea of photography as art. The Lackawanna Railroad Freight Station, with horse-drawn wagons in front, almost kindles notions of Canadian David Milne’s New York watercolours, so similar are the scenes. Pictures of black children and mothers in semi-abandoned streets express a new photography with a social conscience and “decisive moments.” From the Bowery, to a hardware store, to a Fifth Avenue theatre staircase and water fountain, to Mulberry Street to Prince Street to Union Square, you can see how the New York City panorama is, and will always be, ever-changing; even the most constant element, the buildings, are modified over time. The 1950s photographs capturing the essence of a moment, with images of a Daytona Beach hotdog stand and classic cars piled up in a West Palm Beach, Florida, junkyard, are memorable and show Abbott’s conscientious eye for truth.

Abbott’s foray into scientific photography reveals her more theoretical, didactic side. A Parabolic Mirror in Cambridge, Massachusetts (1958–61) is pure Man Ray surrealism. Magnetism with Key and Magnetic Field (1958–61) and A Bouncing Golf Ball Photographed with a Strobe Camera (1958–61) are pedagogical photographs generated by the Physical Science Study Committee, an educational body set up as a result of the United States’ Cold War race with the Soviets after Sputnik went into space. More fun are the Route 1 photographs (1935) that, like writer John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, exude a gritty textural truth: farmers, wood houses and churches, plain faces, gatherings and gas stations. Organized by Gaëlle Morel, curator at the Ryerson Image Centre, this is a must-see show that encapsulates Berenice Abbott’s great character and vision.

John K. Grande is the author of Balance: Art and Nature (Black Rose Books, 1994), Art Nature Dialogues: Interviews with Environmental Artists (State University of New York Press, 2007), and Dialogues in Diversity: Art from Marginal to Mainstream (Pari Publishing, 2008). He recently co-authored Bob Verschueren: Outdoor Installations (Editions Mardaga, 2010) and contributed to The New Earth Works (isc Press, 2011). He recently co-curated “Eco-Art” with Peter Selz at the Pori Art Museum in Finland. Art & Ecology is being published in Shanghai in 2012. Art in Nature appeared in a Korean edition with Borim Press in 2012.