By Stephen Horne

“It is creative apperception more than anything else that makes the individual feel that life is worth living.”

—D. W. Winnicott 1

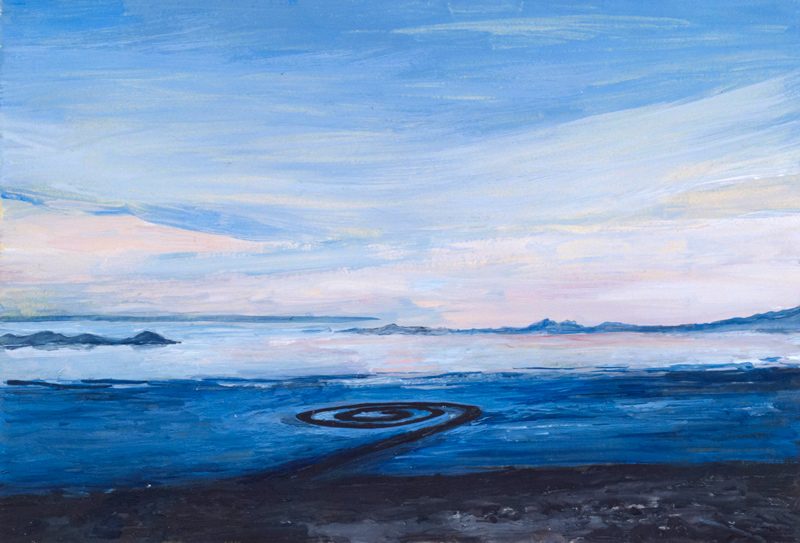

This was Winnicott’s response to the difficult challenge of reconciling oneself to one’s own temporality, a favoured problem for artists from On Kawara to Ann Hamilton to Tacita Dean. Artists have tended to handle this challenge in one of two ways: through an art practice that cultivates a relationship with the past or, conversely, by exploring new forms of subjectivity. However, it is not always a simple matter to discern one from the other. This is the case with Tacita Dean, especially evident in her recent film JG2, a piece that takes on commemorative shape as an ode to J. G. Ballard and to Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. As do many contemporary artists, Dean consistently takes on the problem of time and its meaning. Although both Ballard’s and Smithson’s notions of time remained within a Platonic model in which time is nothing but a continuous decline, in their art they each practised an envisioning of a past future echoing within intricate forms of recollected projections.

Tacita Dean is a member of the YBA (Young British Artist) generation. Her practice is one of retrievals, detritus, recycled surfaces, found pictures, and lost subjects – and, most notably, of time and space integrated. It’s bricolage, the flâneur, and all the Baudelairean poetics brought together very carefully with great concentration and tenderness. She works primarily with film “installations,” and yet her exhibitions confront us with, and solicit from us, a style of haptic attention that is almost painterly. That is to say, touch is of utmost importance to Dean – a point that is made in the various series that she has produced with over-painted (re-touched) photographs and postcards, as well as her large-scale “blackboard” chalk drawings. Her concern with film and photography feels almost paradoxical alongside her dedication to tactile experience; however, it is on the model of a seeing that touches and a touch that sees that she intertwines tactility with technical reproducibility, presence with absence. Dean finds touch imbued with the feel of memory, whether as Benjaminian recollection or as Proustian reminiscence. Touch requires a surface; she has noted that the appeal of working on a single surface, as painting does, holds less interest for her than does a series. Dean’s process is a strategy of anachronism, an artisanal making of things in a world from which thingly being is disappearing in favour of information.

Dean is best known for her commemorative works made in 16 mm celluloid film and her bookworks composed of found photographs, such as the remarkable Floh (2001), a book that foregrounds not only the book form but the indiscriminate quality of photography. At one time her films would have been characterized as “experimental documentary,” but now they are destined for the much looser category of “artist’s film,” works intended primarily for the gallery and the museum. Even so, three of the directors with whom she might be most closely aligned are Werner Herzog, Chantal Akerman, and Chris Marker. Her films are typically loops of about a half-hour in length and rely primarily on techniques to emphasize the durational aspect of viewing as well as the possibility of fiction with documentary. The long take, static cinematography, fragmentation and close framing of the subject, minimal narrative, abundance of still shots, natural lighting, and optical sound all contribute to the viewer’s awareness of the time and space of production. In many cases, the projection apparatus itself is part of the gallery installation, as was the case with her film Merce Cunningham Performs STILLNESS…, shown in Montreal last year, in which multiple projectors were “choreographed” into the film installation. These various practices and techniques lead toward a work of art that works by commemorating its own existence in time and space, as well as that of the viewer, whose sense of time is inevitably conditioned by an awareness of mortality. Dean’s concern with memory is in fact her compassion for the momentary, for the event, that extended and ambiguous happening of a “now” that is the flux of time.

JG is a twenty-six-and-a-half-minute 35 mm anamorphic (wide screen) film-loop projection for gallery or museum space. Dean has more typically used 16 mm, but in this case the larger format was required to accommodate an ingenious system that she invented by which stencils are inserted into the camera’s aperture gate. These templates add a mechanical and physical impact to the projected image, which reaches a peak of intensity in a screen-filling spiral through which orange sunlight floods, moving first from right to left, and later from left to right. The tactile mechanicity of the stencilled spiral in juxtaposition to this flood of sunlight highlights the consistently hand-worked drama of Dean’s engagement with the technology of reproducibility.

As a proponent of dystopian vision, J. G. Ballard is an explicit precursor to Robert Smithson and his concern with time construed as an entropic process of decline, of time running out or down. Ballard’s titles read like memos sent across time or left in waiting for Smithson: his short stories “The Voices of Time” (1960), “The Drowned World” (1962), and “The Crystal World” (1966) all sound like instructions whispered in Smithson’s ready ear, instructions that he developed both in written explication as well as his “earthworks,” including the sculpture Spiral Jetty. This piece is the ostensible topic of Dean’s film JG. Spiral Jetty is pertinent for its having been “lost” underwater since its construction by Smithson in 1970. In a narrative of remarkable coincidences, Ballard actually proposed to Dean, just prior to his death in 2009, that she “solve the mystery of Spiral Jetty.” Coincidence and its mysteries are in fact already the stuff of Dean’s art practice, as is ironical use of analogue film to commemorate its own disappearance. Strangely, however, Spiral Jetty has reappeared, the waters to which it was lost as the Great Salt Lake rose in the 1970s having now receded. The film plays out Dean’s interest in extreme and unusual landscapes and incorporates images seemingly taken from Ballard’s dystopian vision of once-futuristic machines now encountered as dysfunctional artefacts, wheels autonomously and gratuitously churning canals of sluggish salt and water. This uninhabited landscape is overlain with voice-over quotations by Smithson and Ballard, one of the more remarkable being Ballard’s “Robert, I have to tell you. Even the sun is growing colder.”

A series of over-painted postcards were also included with JG in Dean’s recent exhibition at Galerie Marian Goodman3 in Paris. The original cards are all anonymous but for one, which caught my interest due to its identification as a work by Caspar David Friedrich, the quintessential German Romantic painter. Of the dozen or so images, it was the only one with any source identified, marking the figure of Friedrich as particularly relevant. Dean’s affinity for German romanticism is further evidenced with her film commemorating Joseph Beuys and his biophiliac vision for healing and earthy fundamentalist social program. (Dean has been living in Berlin for the past ten years.)

Dean has made films commemorating creative individuals whose work has also involved the themes of narrative, history, memory, and writing: W.G. Sebald, Michael Hamburger, Cy Twombly, Mario Merz, and many others. What they all have in common is their interest in correspondences between writing or “indexicality” and the phenomenon of ageing, mortality, and proximity to death – that is, nature – but also the problem of ending as it is for narrative structures, narrative mortality. Dean’s films, in good romantic spirit, engage intimately and even playfully with mortality, its charisma, and the charisma of creativity. This reference to nature is made explicit in her many films featuring events of nature, such as sunset (The Green Ray, 2001), eclipses of the sun (Banewal, 1999), another solar eclipse, (Diamond Ring, 2002), and birds (Pie, 2003), and in her vast personal collection of clover leaves of the four-, five-, and six-lobed varieties. Dean has no aversion to superstition and the magic of coincidence.

This world in which touch and memory intertwine is the world of experience as described by H.-G. Gadamer, among others in the tradition of hermeneutics. When Gadamer discusses experience, art is a fundamental reference in his analysis. Crucial to his notion of experience as something we “undergo” is that of the “event,” “. . . something unforgettable and irreplaceable, something whose meaning cannot be exhausted by conceptual determination.”4 His sources are in that romantic subjectivism concerned with challenging modern technicity, and in this sense Bernard Stiegler. These figures are all pertinent to a discussion of both Smithson and Dean on the basis of their concern with what Smithson called “continuance.”

What Ballard, Smithson and Dean mean by invoking this sense of a lost “continuance” is the sense of a lost belonging in time and place, a loss of solidarity within collectivity, of place within an ancestry and participation in a shared future, but also the sense of futility regarding the human being as an unfinished project alongside the adventure of shared uncertainty. In this sense, the explicit longing and nostalgia that characterize Dean’s work are not only a nostalgia in which the subject is the past, but, more importantly, what she identifies as a future being lost in an ever-greater technological anomie. The evaluation that sidelines artists such as Stan Douglas, Eija-Liisa Ahtila, and Dean on the basis of their concern for recollection and memorialization is simply another demonstration of contemporary alienation. J. G. Ballard’s focus on a past dystopian future echoes that of Kafka, who describes an autonomous technology, the dehumanized version of post-humanism in which the space of human lack is made up for by a culture machine that works by itself.

With regard to the issue of “continuance,” it is helpful to situate Dean’s work with respect to the recent writing of the philosopher of technology Bernard Stiegler, whose critique in recent years has been prodigious and influential. Echoing Winnicott and as a former student of Derrida’s, Stiegler, in his most recent writings, emphasizes his concern that the path of technology has bifurcated and the version now in the ascendancy has taken on a distinctly dystopian, anti-humanitarian direction of the sort predicted in Ballard’s stories of the 1960s. Stiegler argues that the ongoing shift toward totalizing efficiency rejects value and the spiritual connection to durable objects that can make life worth living. What is also intriguing in his analyses is his position with regard to the relationship between technology and nature: no Luddite, he argues for the co-determination of one by the other, saying that humanity invents itself by inventing technology, which is the invention of time and space, and here his account overlaps with those of Ballard, Smithson, and Dean: the end has meaning for us, but technological becoming is endless, and its “progress” relentlessly disrupts embedded cultural formations (Smithson’s “continuance”) in its drive toward order, calculation, and efficiency. Dean’s consistent involvement with obsolescence and decay is not a retrogressive perspective but an attempt to sustain an opening from which alternative futures and différance may be drawn. What is remarkable in Dean’s practice is her ability to celebrate the uniqueness of a person’s existence, an artistic achievement, an event of nature, or a moment in time, within the paradox of technical reproduction, once believed to be an overcoming of uniqueness and the aura in favour of a democratized culture. Dean’s memorializations exemplify a concern for a “continuance” of the future as a human project, and a resistance to the totalitarian project of reality lived as order, calculation and efficiency.

2 JG, film commissioned by and presented at Arcadia University Art Gallery, Glenside, Pennsylvania, 2013.

3 Tacita Dean, JG, exhibition held at Marian Goodman Gallery, in Paris, from January 3 to March 1, 2014.

4 Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, trans. Joel Weinshiemer and Donald G. Marshall [1975] (New York: Continuum, New York, 2004), p. 58.

Stephen Horne is an independent curator and writer living in Montreal and France. He has taught at NSCAD and Concordia Universities and is published in periodicals, catalogues, and anthologies in Canada and elsewhere.