[Spring 2009]

We live in an age of disappearances, a time of loss and change, with mass extinctions and vanishing eco-regions. These profound, sinister planetary transformations remind us of the intimate link between ourselves and our actions in the visible world. Yet it seems as if this rapid unravelling has left us dumb with dread and anxiety. How are we to make meaning out of it? Oscar Muñoz is one artist who has consistently worked toward understanding the harshness of this reality by allegorically addressing Colombia’s violent civil war and its remains and disappearances. Born in Popayán, Colombia, Muñoz studied visual arts in the neighbouring city of Cali at a time when photography was not being taught. Instead, he honed his formal and conceptual skills by drawing photographs of architectural interiors. For three decades, he has been using photographic fact as a reference and a metaphor to create conceptual works that are somewhat akin to the twinned processes of life and death by using materials such as water and coal dust, and methods of pulverization, reduction, construction, and destruction.

by Elizabeth Matheson

During the 1990s, at the height of the very violent conflict between the state and notorious Colombian drug cartels, Muñoz decided to create Ambulatorio (Ambulatory, 1994–95), which he has sited in various locations, beginning with the streets of Cali. Minimalist in style but rich in meaning, the design is an immense, sombre black-and-white aerial map of the city of Cali – an astonishing image, and all the more so for having been covered by shattered safety glass for the passerby to walk upon. This allowed Muñoz to handle overtly political subject matter with a delicacy that would otherwise be nearly impossible to achieve as he managed to mirror the city’s dissonance with a fractured image that at once obfuscates any sense of purview of this contested territory, yet also begs the question of the relationship between the viewer and the struggle for the city itself. The viewer’s steps crack the surface further until only glass particles remain encrusted in the cracks of the pavement, evidencing the connectedness of all things. Muñoz has stated, “I like the idea that something that generally functions with ephemeral, with the temporal, with the instant can have a lasting effect… that transcends the actual experience of the work. In this sense the work might move at a level beyond that of political discourse… it is the poetic value of a work that can potentially transform a person.”1

Oscar Muñoz…allegorically address(es) Colombia’s violent civil war and its remains and disappearances.

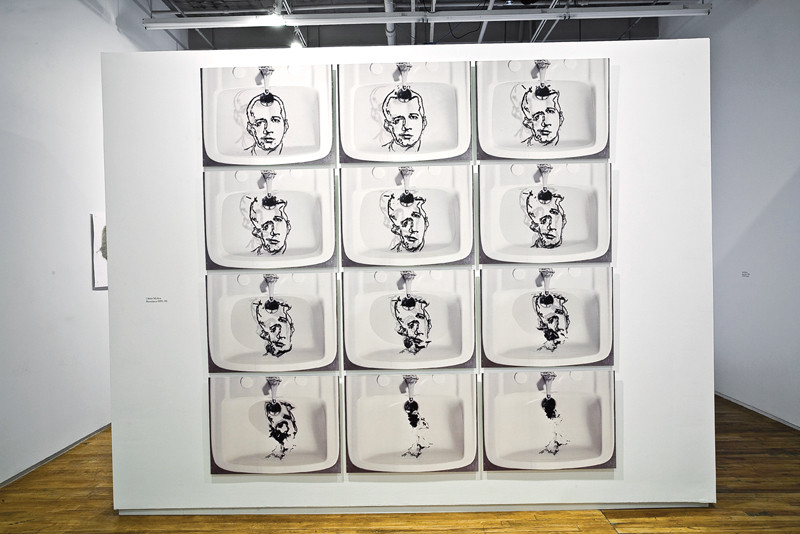

Narciso (2001–02), often presented as a single-screen video, contributes to a poetic reading of Muñoz’s works, but also introduces an important aspect of his oeuvre – his liberal references to mythological love, death, destruction, and transformation. The artist screened a line drawing in charcoal of his own face onto a sink full of water, allowing the image to float on the surface, reflecting a dual image of itself through its shadow. As the water slowly begins to drain out of the sink, the image seems all the more powerful as the portrait and its shadow appear to momentarily reunite, only to become more and more distorted. This evocation of the myth of Narcissus has been used by many artists as an act of self-conscious inquiry or artistic self-reflection, but it seems that Muñoz is all too aware that our modern tragic flaw is not knowing ourselves but our inability to coexist with ourselves or the environment. As a consequence, we come to grief over our failure to be committed and compassionate.

This is signalled in Muñoz’s work Re/trato (2003) whose sole visual image is a close-up shot of the artist’s hand persistently attempting to preserve a self-portrait painted in water on a stone heated by the sun. Much like a fleeting memory, the artist’s portrait can never be seen as a whole and is never exactly the same. Using Re/trato as the point of departure, Muñoz presented his ongoing exploration of the repetitiveness and struggle in human life in Proyecto para un Memorial (Project for a Memorial, 2005). The five synchronized single-channel videos show the artist’s hand rapidly moving from one screen to the next rendering portraits of people in quick strokes of water on hot pavement. His hand remakes the images from one screen to the next in a futile attempt to complete each portrait before it evaporates. Who are these people who vanish under the sunlight? His subjects are not political leaders or members of affluent families but ordinary people whose images have been taken from newspaper obituaries, many of whom died from the recurring violence in Colombia.

In fact, Muñoz’s approach to his medium may be elaborate because he makes his images often with not only ephemeral substances, such as water and coal, but also with the lived essence of viewers – their own sight, breath, and touch. For an exhibition last summer at Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts), his first solo exhibition in the U.K., Muñoz re-created his installation Eclipse (first mounted in Galeria Santa Fe in Bogotá). At Iniva, small holes made in the gallery’s wall to reveal the outside cityscape were covered by a series of circular concave mirrors arranged at varying angles, creating patterns of dark and light like the stages of a lunar eclipse, symbolizing a continuous cycle of time. Upside-down images of the outside street were projected onto the mirrors, putting viewers in a position where they needed to move in close and look around the screens to see what was transpiring outside the dark gallery. This mirror-world also created a sense of the transience of life by bringing unexceptional moments of the city into the darkened gallery – people carrying packages and setting off to work – which, like the interrupted meal in a Baroque allegorical painting, depicts the most inconsequential everyday moments, but in a profound way.

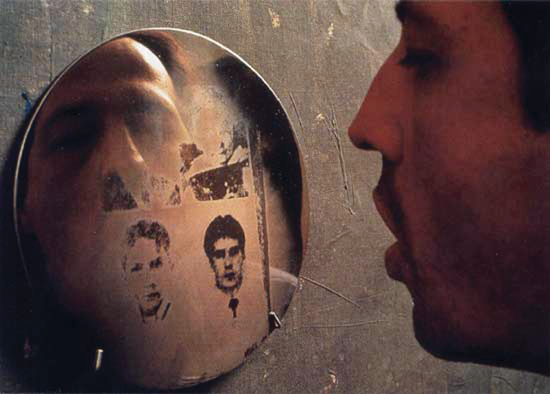

Another work, Aliento (Breath, 1996–2002), is composed of a series of polished steel disks placed on a wall. As in a mirror, the viewer’s reflection can be seen in each disk surface, but even a slight breath upon the surface produces an image of a person momentarily surfacing from the nether world only to withdraw again. The fact that the portraits originate from Colombian obituaries has an implicit politics, embodied in the heartfelt urgency of their momentary resurrection, underscoring the humanity of breathing life into these “victims” who remain largely invisible in the economic and social currents of the country. Exhibited alongside Aliento was Paistempo (2007), a collection of printed versions of two major Colombian national newspapers, Pais and Tiempo, that perhaps most vividly embodies Muñoz’s assessment of the human condition. To produce them, the artist painstakingly used a pin to burn the written texts and images of lost lives and moments never to be recovered, making them, like other things in the exhibition, small monuments to the cut and thrust of living each moment. It is a piece that brings to mind the last chapter of Albert Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), in which Camus ponders Sisyphus’s thoughts as he marches down the mountain to start anew in his singular poetic action.2 For Camus, the tragic moment when Sisyphus becomes conscious of his condition allows him not only to accept this fate but to understand the mutability and interconnectedness of the cosmological world. In referring to this mythological act, Muñoz has stated that within such repetitive gestures, attempts and re-attempts, there is also something to be recouped in the face of deathly indifference, more multivalent and rewarding than lamentation. Our world will unfold regardless of humanity’s will for permanency but, as Muñoz’s work suggests, even when the impossibility of the task is laid before us, we persist and keep pushing.

Elizabeth Matheson is an independent curator and writer on Canadian and international contemporary art and culture.