Our expeditions usually begin at first light. This time, Stephen explained, we would be better to hold off until the worst of the rush hour had burnt itself out. I sat on the church porch and waited, admiring a procession of those bright-red sculptural interventions held long enough at the traffic lights to catch the appreciative eye, the new Stagecoach buses with the NOT IN SERVICE destination windows. Stalled under the railway bridge and shuddering slightly, like overbred racehorses, this convoy of scarlet cardinals basked in autumn sunlight. In their aura of expensive entitlement.

It was good to be alive and out in the streets again. Launched on another adventure. Over recent years, our part of the city had stopped being a discarded library book filled with obscure facts and teasing memorials to dead writers and been rebranded as a perpetually overpainted, self-cannibalizing graffiti gallery. I noticed that a poster inviting us to “make poverty history” had been improved with an aerosol representation of a life-sized Orwellian tramp hunched up on the pavement. The poster covered the space of a hidden door.

“I love that blue, the way it’s disappearing.”

Stephen’s art – and I regarded him as a major resource, a master of the territory – is about love. Discriminations of love. Love as anger. Love as notice, staying alert to flaws, follies, civic impositions. He catalogues the spectacularly mundane: junked betting slips, cans of energy drinks, albums of wedding photographs. But he is always positive. His work is as much an excuse to be out there, on the move, tramping, cycling, pumping up his kayak, hopping a random train, as a requirement to make prints, put out books, curate exhibitions. Take away his camera and he’d draw with a felt-tip pen on his eyeballs.

“Years of Bethnal Green sunlight went into making that colour. The blue has faded so beautifully.”

Stephen is one of the few people to appreciate the old railway bridges as bridges. As unofficial gates or portals to the next zone of London. But today his new project requires a later start. He’ll be standing in the middle of the road poking a long pole into the hidden crannies under a succession of railway bridges. There are many bridges, many feathers, fallen nests.

We walk west.

My guide is dressed like an urban fisherman: soft blue hat with no flies in the band, blue protective jacket, loose trousers, heavy boots. He is carrying a bulging bag and a silver pole. He calls a halt where Collingwood Street emerges from Three Colts Lane.

“Look at that,” Stephen says.

The arched roof of the tunnel under the railway was scratched with claw marks, long yellow-orange striations revealing the original glow of the bricks beneath generations of thick grey sludge-varnish.

“Overloaded vans heading south to the scrap yards,” Stephen revealed.

The white goods heaped on numerous Transits had gouged at the curve of the low ceiling. The lane going north was untouched. Stephen was a connoisseur of blight, but this bridge didn’t answer. It was not a promising spot to begin our fishing. He knew the ways of the river-roads and the silver streams of the railways, as a true native. A hunter-gatherer of images. On our walk from Cambridge Heath Road, he pointed out the remediated warehouse where he had kept a studio for many years; the site from which he had launched his dawn raids on disputed terrain. The former inhabitants had been priced out, then expelled: all those fugitive printers, photographers, invisibles. Even the junkies shooting up in the metal box of the lift.

“I was on the spot. I could watch the trains from my window. I could cycle off up the Lea Valley. I could work all night in the darkroom. Go for a wash to York Hall.”

And now? Enclosed. Scaffolded. Another investment opportunity. Make your purchase, sight unseen, in Kuala Lumpur.

The silver fishing pole is extended. Stephen is happy with this new pitch, the pool of shimmering ghost-light under the second bridge. “Listen,” he says. “Feel it. The ripple and shudder of the Stansted Express.” Planks tremble. Girders sigh. Now his pole looks like the prosthetic arm of a manic soundman trying to capture the hiss of expanding metal joists. He purchased it, so he told me, in a useful hardware shop on Hackney Road. The telescopic pole is intended for use by window-cleaners. Stephen has adapted it for his camera. We don’t need to see the prey, we can smell it: burnt marzipan blended with diesel soup. Like marsh gas trapped in the bones of a plague pit. Like unsponsored, post-historic London. Stephen has the clothes, the camera, the whippy rod. He’s forgotten the surgical facemask. The reluctant subjects of his investigation are tribes of feral pigeons who have infested these arches since the coming of the railways. They have seen the days of trading in exotic animals – lion cubs, parrots, monkeys – come and go.

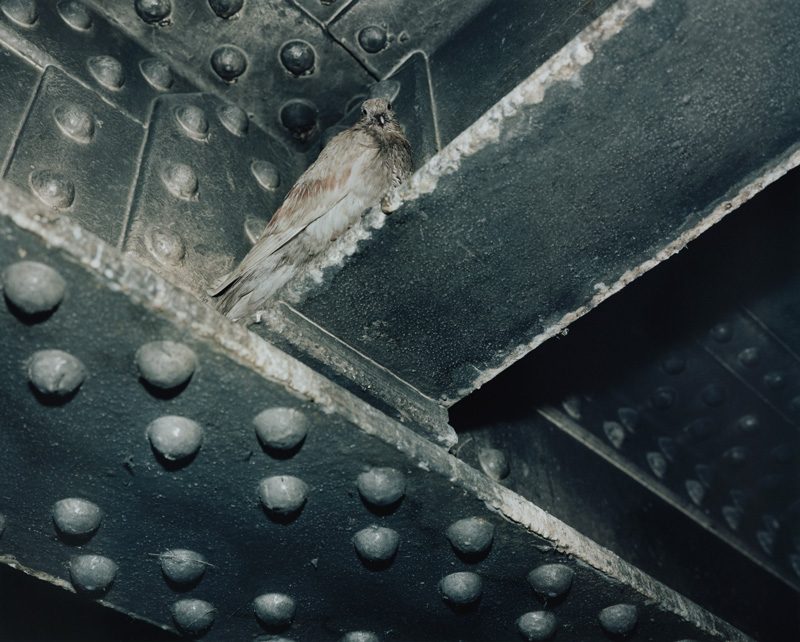

The peculiar and unquantifiable magic of the area derives from the Victorian invasion by canals and railways: secret caves for dealers, hucksters, illegitimates. Stephen is celebrating the private life of the much-maligned pigeon colonies: grey and spectral coops within the dignified ironwork of the railway’s epic engineering. Birds are like dead souls nesting on stalagmites, on conical reefs and mounds of their own droppings. Eons of acid excrement eating into metal. We have never witnessed these creatures in such enclosed settings: so defenceless, taken by stealth. They are ruffled, agitated by the shock of the harsh flash. The avian portraits, over which Stephen has limited control, are pure revelation. They chart previously unrecorded London life, one of those tiny pockets left outside the intrusion of surveillance systems.

Pilgrims, mostly Asian, passing through the tunnel as through a border crossing between worlds, notice the image-fisher but choose to leave him alone, without comment. The long pole wavers. Stephen stands, he raids. Traffic swerves. He counts aloud, his camera is primed: “One-two-three . . .” After twelve seconds, the flash detonates. Stephen is shooting blind. He won’t know what he’s got until he makes the print. All too often, the birds explode in an aggrieved spatter of wings, like the sound of an echoing, reverberating chamber of ironic applause. They circle, swoop, settle, regroup on the steep roof of new flats erected in Vallance Road. Such souls as managed to transmigrate from the period of the original close-packed terraces have another existence in pigeon purgatory.

A young bird, fallen from the nest, still pink of belly, thrashes on a ledge, unable, so it seems, to take flight, but unwilling to fall to the ground, trapped in restless Sisyphean torment. A metaphor for some of the horrors of place. With nothing to be done.

The strangest aspect of Stephen’s pigeon séance is that nobody challenges us, two men poking a silver rod up under a railway bridge. A rod with a camera attachment. And a brutal flash (the kind that conspiracy theorists claim blinded Princess Di’s driver in the underpass). In surveillance city, where public image-making is seen as suspect, if not criminal – “Don’t you know there’s a war on?” – fishing for pigeon portraits passes without comment. Until a local matron, dog on a string, approaches. “You’re doing it wrong, gentlemen. You’ll never get rid of them that way. I’ve lived here thirty years and I’ve tried everything. But they still land on my head every time I set foot on the street. They think they fucking own the place.”

Born in 1971 in Bristol, UK, Stephen Gill became interested in photography in early childhood. His work has been exhibited and is held in collections at international galleries and museums including London’s National Portrait Gallery, the Tate, the Victoria and Albert Museum and The Photographers’ Gallery. He has had solo shows at festivals including Les Recontres d’Arles, the Toronto Photography Festival, and PHotoEspaña. Gill has also gained recognition for his numerous self-published photobooks, including Invisible, Hackney Wick, Archaeology in Reverse, Hackney Flowers, Buried, Coming up for Air, A Book of Birds, Coexistence and Best Before End. Gill had a major solo exhibition at Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam in 2013. The Pigeons series was recently published by Nobody Books.

www.nobodybooks.com

www.stephengill.co.uk

Iain Sinclair has lived in Hackney (London, United Kingdom), since 1969. His books include Downriver, Lights out for the Territory, London Orbital and Edge of the Orison. His most recent publications are Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire, and Ghost Milk.