An interview by Alexis Desgagnés

Photographs by Benoit Aquin

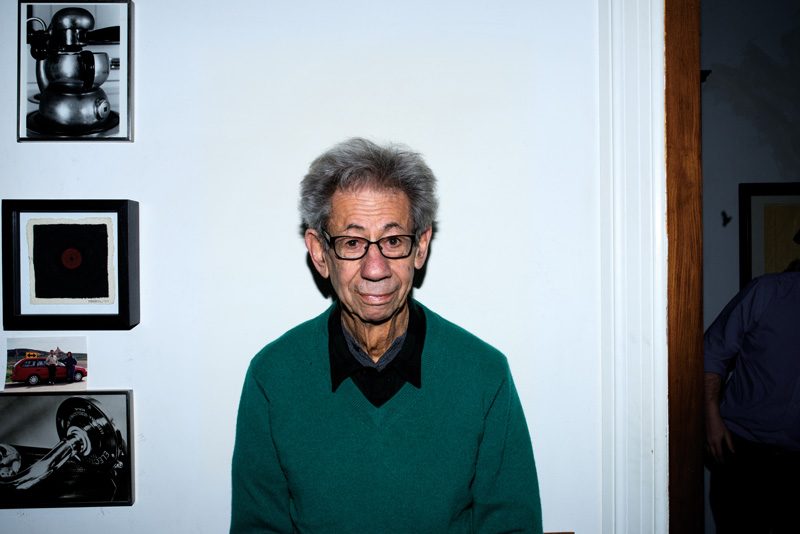

Eighty-eight years old. Decorum would have us qualify this age as venerable. Anyone who divides this number into decades will better measure the span of a lifetime devoted almost entirely to photography. We know about the immense contribution of Gabor Szilasi, who was born in Budapest in 1928 and arrived in Quebec after leaving Hungary in 1956, to the history of Quebec photography. I will calculate it for you: he has been surveying the landscapes of our photography with his cameras for almost sixty years. Charlevoix, the Beauce, Abitibi, Montreal, Quebec City, and many other locales have supplied him with the subject for an essential body of work resolutely documenting “reality,” a recurrent concept when he evokes his relationship with the world that he has known and photographed. Contemplating his age, I wanted to meet the Szilasi of 2016. One March day as winter was ending early, I visited him in Westmount, where he and his wife have lived for many years. A few days later, Benoit Aquin joined me to produce the humble homage that is this portrait of Gabor Szilasi in interiors.

AD: Naturally, to begin, how are you?

GS: I’m eighty-eight. So, I don’t take many photographs, but I’m preparing, with Zoë Tousignant, an exhibition of negatives that I never printed and that form a record of artistic life in Montreal from the 1970s to 1990s. I’m planning to make silver prints . . . if I still have the energy!

AD: So, you’re still working in the darkroom. How often do you print your photographs?

GS: Let’s say, in general, I make prints once a week. But it also happens that I work three days in a week, and after that I don’t work for three weeks. What I accomplished in thirty minutes twenty years ago, now, it takes me two days. I remember. Sometimes I printed twenty photographs a day. Now, four or five . . .

AD: Would you like to do more, or do you accept that this is now the pace you work at?

GS: I’d like to do more, but the prints have to be really well done, which takes me much more time than before. But my health is very good. I pay attention to what I eat. I walk, do the shopping, because I cook, I really like doing stuff in the kitchen.

AD: In her beautiful film L’esprit des lieux (2006), Catherine Martin revisits your corpus from Charlevoix in the early 1970s. Returning thirty-five years later to the places shown in your images, the filmmaker says, in a subtitle, that she wanted to retrace your footsteps to take “the measure of what remains and what has disappeared.” In this spirit, I’d like to know what remains today of the world that you have photographed your entire life.

GS: When I arrived here, I discovered the rural regions of Quebec, the peasants, the farmers . . . realities that I didn’t know about in Hungary because I grew up in Budapest. There are things that have disappeared – mainly, a way of life. In Charlevoix in 1970, the Catholic religion was still very important. Barely three years later, I went to the Beauce, where there were industries, and people were already less pious. So, yes, things change.

I’ve always been very interested in reality. I’ve never done romantic landscapes. I’ve done landscapes where you find traces of men and women, contemporary life, their environment, social changes. . . That’s why I went back to Abitibi a number of times, to see the change. It’s in Abitibi that you saw the trace of religion the least. Maybe ten years ago, I did some work on three industrial cities for the Canadian Centre for Architecture: Shawinigan, Témiscaming, and Arvida. The social changes were really visible in their architecture.

AD: Do you sometimes feel nostalgic for what is gone, what has fallen away?

GS: No. I made an observation and I accepted the changes, because I find that very interesting. I’ve photographed many interiors that have been called tacky or kitsch. I never had that feeling because, for me, people were simply expressing their attachment, their love of colour and strange objects. I found that natural. I haven’t travelled recently to the regions I photographed, but I wonder if it has changed, if young people in the countryside still have the same taste today for vases, lamps . . . Anyway, many of those young people want to move to the city. But, in the Gaspé, I recently met young people who, after getting their education in the city, felt the need, when they were around thirty, to return to their country.

AD: You said a bit earlier that you take fewer photographs than before, but I presume that you still take a few. I’m curious to know what interests you, what you photograph today.

GS: I was recently approached to photograph artists who are about my age and still active – for example, Françoise Sullivan, Antonine Maillet, and Edgar Fruitier. For about ten years, I’ve also been part of a group of Quebec poets who meet every two weeks in Lafontaine Park. I take portraits. In this group are Michèle Lalonde, Patrick Coppens, Claude Haeffely, Violaine Forest. I’d like to put together a publication inspired by one of the first photobooks I owned, Paris des rêves (1950) by the photographer Izis, in which the photographs are associated with texts by contemporary authors: Cocteau, Henry Miller, Cendrars.

AD: You began to take photographs in the early 1950s. What drew you to this medium?

GS: I always loved art. At the time, I was drawing a little, but I didn’t have much talent. When I looked at the photographs by Kertész, Cartier-Bresson, the early photographs taken by Avedon in the streets of Paris, I told myself that taking photographs was simple: a little movement with the right index finger, and there was an image.

AD: So, even at the origin of your practice, there was still a desire for artistic expression?

GS: Yes. Definitely. Another important influence for me was reading. I very much liked the Russians – Chekhov, Dostoyevsky – but also Balzac. Le Père Goriot, is really . . . reality, daily life. My readings didn’t directly influence my photography, but my life philosophy, my daily life.

AD: And your interest in the relationship between women and men and their environment?

GS: Yes. And film also. Let’s say, for my photographic style, the post-war Italian films. And French films, too.

AD: And the concern for realism that has always been with you, is it still with you today?

GS: Yes, it’s still with me. For example, I was never drawn to photographing people with a certain reputation, who are very well known, because when one looks at a picture of Marilyn Monroe, rock musicians, a politician, it’s difficult not to be influenced by their reputation. How do you take a bad photograph of . . . I don’t know . . . Céline Dion?

AD: The word “reality” comes up often when you speak. In fact, it’s the heart of your approach, so that would be a quest for reality.

GS: When I photographed rural regions or Montreal, an important thing for me was that the photograph return to the community. When I took a second trip, I always distributed the photographs taken before, and that enabled me, in turn, to meet other people. It’s very important not simply to take images, but also to give them back.

AD: An exchange, in the end – a dialogue, a discussion. During your career, have there been remarkable encounters, people who really dazzled you?

GS: Certainly encounters with other photographers, other artists, such as Robert Frank, who I met in Montreal, who put me up in New York and came to Concordia a few times. The aesthetic of his films, his whole philosophy of intimacy, The Lines of my Hand . . . Another encounter was André Kertész, whom I visited in New York. His address was 2 Fifth Avenue, the first house on the avenue, looking onto Washington Square. I adore his work. What I really appreciated about Kertész was that he did so many things, in so many styles. He experimented a great deal.

AD: Gabor, you’re eighty-eight years old. Your work will outlive you. What would you like people to retain of your gaze on the world in general, and on Quebec in particular?

GS: I think my contribution will have been to describe, to show, life, here, in the late part of a century.

AD: At your age, do you think more of the past or the future?

GS: For me, it’s the present. That’s why, in photography, the 125th of a second says everything. Because the next 125th of a second, it’s different.

AD: Do you press the shutter only at the moment when you feel that you’re fully present in the situation photographed?

GS: Yes. Especially when I’m working in large format. It’s very difficult to do thirty-six poses with a 4 x 5. For many of my photographs that are known, I did just a single pose. I don’t know . . . the portrait of Mme Tremblay or the two women in front of the church door . . .

AD: I’d like to ask you a question that’s a bit awkward, but that, in my view, is natural to ask when one speaks with experienced artists such as you, and also because culture is essentially an affair of transmission. To conclude our conversation, do you have any advice for young Quebec photographers?

GS: Above all, no matter whether a photograph is silver or digital, it’s always the image that counts. Also, it’s good to be influenced, but you shouldn’t imitate. Look at images by the photographers you like, in any style. You may photograph the same subjects, but you must do it in your own way. And take lots of photographs. And look at them carefully and ask yourself, “Why did I take this photograph?” Don’t worry if you’ve done something that has already been done, because if you do it in your own way, it will be unique. Translated by Käthe Roth

Alexis Desgagnés is a Quebec art historian, artist, and author. His book Banqueroute, a collection of poems and photographs, has recently been published by Éditions du renard.

Purchase this article