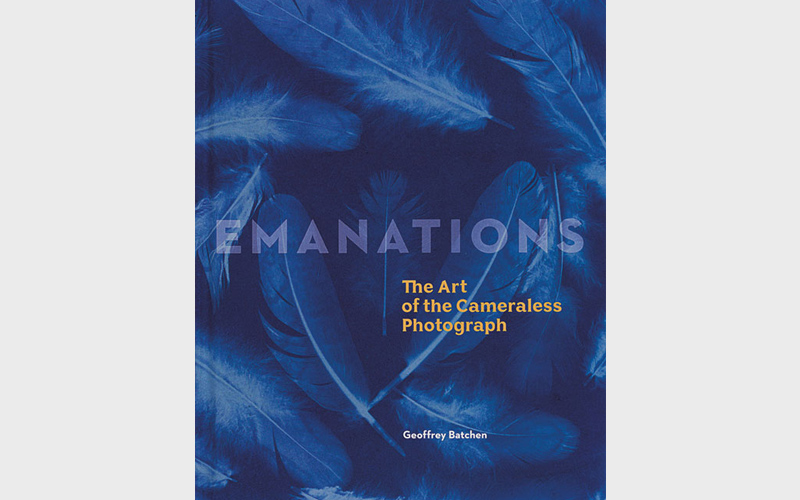

Munich: DelMonico Books; New Plymouth, NZ: Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, 2016

Par Claude Baillargeon

Published to coincide with and provide a broader context for a similarly titled exhibition, Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph surveys a vital form of image making traditionally relegated to the margins of the medium’s history. Its author, the renowned art historian Geoffrey Batchen, based at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand, also curated the companion exhibition for the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery located in New Plymouth, New Zealand. Although many artists are featured in both components, the publication aims to present a more global overview that is less susceptible to the limitations and exigencies of exhibition curating.

In contrast to Batchen’s more theoretically engaged reflections on photography, Emanations is, by the author’s own admission, “primarily a picture book” (p. 199). Notwithstanding this acknowledgment, it should not be misconstrued as merely a coffee-table book. On the contrary, it can be argued that Emanations exemplifies how a carefully conceived visual essay can be effective as a form of discursive practice. What better way is there to demonstrate that “throughout photography’s history the cameraless photograph has always been a subversive element, an autocritique of everything that photography is supposed to represent” (p. 47) than to rest one’s argument on a cross section of highly diverse images from all periods and locales?

Emanations is lavishly illustrated with 144 plates and 33 in-text figures, all impeccably reproduced in full colour, with the scale of individual images (representing works ranging from 6.0 × 8.0 cm to room-sized installations) intuitively adjusted to modulate their sequential reading. Complemented by an unobtrusive design eschewing images that are full-bleed and spill across the gutter, the sequence is mainly chronological, though one suspects that the final selection of images must have been determined with their pairing in mind. The fact that Batchen’s essay addresses each plate in the order in which it appears strongly suggests that he deserves credit for the often-exquisite pairing of images and their overall sequencing, both of which are conceptually and visually driven.

To anchor this portfolio, the publication opens with a lengthy essay structured in six chronologically arranged sections: “The Pioneers,” “The Wonders of Science,” “The Avant-Garde,” “Between the Wars,” “Postwar,” and “Toward the Present.” It concludes with a coda summing up why cameraless photographs matter.

In his introductory remarks, Batchen underscores the essential difference between cameraless photographs and their lens-based counterparts: “Unmediated by perspectival optics, photography is here presented as something to be looked at, not through, and to be made, not taken. After all, a cameraless photograph is not just of something; it is something.” Thus, Batchen continues, “photography is freed from its traditional subservient role as a realist mode of representation and allowed instead to become a searing index of its own operations, to become an art of the real” (p. 5). Intrigued by the profusion of committed photographers who made or are making cameraless photographs, Batchen formulated two questions to guide his inquiry: “Could it be that putting the camera aside has allowed them to experiment in creative ways with their medium that would not otherwise be possible? Can one in fact impart ideas or experiences in these kinds of photograph that can’t be expressed in other ways?” (p. 5).

As he strove to answer these questions, Batchen surveyed the field far and wide, making a concerted effort to reach beyond the established canon. By availing himself of a wide array of recent scholarship, not only in English, but also in French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Polish, and Czech, Batchen successfully integrated within a single narrative several lesser-known figures alongside more familiar ones. Furthermore, his proficiency in addressing both historical and contemporary practitioners enabled him to trace a detailed account of cameraless photography from a global perspective mindful of cultural and ethnic diversity. Thus, in addition to the expected contributions of William Henry Fox Talbot, Anna Atkins, Man Ray, László Moholy-Nagy, Frederick Sommer, Floris Neusüss, Robert Heinecken, and Adam Fuss, we encounter engrossing works by August Strindberg (Sweden), Marta Hoepffner (Germany), Miroslav Hák (Czechoslovakia), Luigi Veronesi (Italy), Lin Shou-yi (Taiwan), Nakaji Yasui (Japan), Pierre Cordier (Belgium), Bronisław Schlabs (Poland), Anne Ferran (Australia), Roberto Huarcaya (Peru), Lynn Cazabon (USA), and Zhang Dali (China), to name a few. Where the selection falters, however, is in gender equity, since only 15 percent of the artists represented are women. Given Batchen’s prominence in the field, it is incumbent upon him not to perpetuate the status quo.

Although Batchen’s ambitious reach is self-evident, it is worth noting that he made no claim to author a comprehensive history of the cameraless photograph. Indeed, one can easily think of other accomplished figures similarly deserving of critical attention, including many featured in the earlier overviews mentioned in the acknowledgments (p. 199). What Batchen aimed to achieve, instead, was “the telling of a distinctive little history of photography, a history with a global reach but discernible boundaries, a history that is self-consciously about the telling of any such history” (p. 47).

Among the many trenchant observations to emerge from this account is the recognition that many contemporary artists “inherit and reflect on the modernist heritage,” which established two primary modes of production: pictures that are made “grounded in the real world or let loose to create a visual experience peculiar to themselves” (p. 38). As Batchen notes, the exploration of this “dual capacity” informs much of contemporary production, oftentimes within the scope of a single artist’s career.

A case in point is the work of Michael Flomen, well known to the readership of Ciel variable (see issues nos. 32, 70, 84, and 97), who is represented by a photogram in which he uses the bioluminescence of male fireflies to record their movement through space and time. As one peruses Emanations, it is striking to observe many works prefiguring aspects of Flomen’s practice, the most unmistakable connection being Fritz Goro’s 1945 documentation of the bicolour glow characteristic of bioluminescent “railroad worms.” An even earlier photogram by the surrealist Jacques-André Boiffard echoes not only Flomen’s work with flies and spiders, but also his more recent experimentations with handmade glass-plate negatives, which make a virtue of flaws and inconsistencies. Other works, such as Max Dupain’s Rayograph from circa 1936, which uses strong raking light to defamiliarize water droplets resting on photo paper, and Heinz Hajek-Halke’s Light Play from circa 1944, “made by mysterious means, a combination of chemical and mechanical manipulations” (p. 34), strikingly anticipate Flomen’s diverse working methodologies, as do Susan Derges’s more recent underwater exposures. The breadth and diversity of Batchen’s survey makes it possible to trace similar parallels and relationships between other contemporary figures and their forerunners.

All in all, there is little to quibble with in Batchen’s erudite essay or in the publication as a whole, except the gender imbalance already noted and the absence of an artist index, which would facilitate research. Ultimately, the success of this publication rests on two closely interwoven components, both well resolved. On the one hand, Batchen has assembled a rich and diverse sampling of representative images, each testifying in its way to the unique creative and expressive potential of the cameraless photograph. On the other hand, his detailed probing of these images, the context of their production, and their significance vis-à-vis lens-based photographs makes it increasingly difficult to continue treating them “as second-class citizens” (p. 5) within the larger history photography.

Claude Baillargeon is an associate professor of art history at Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan. He currently serves as vice-chair of the Society for Photographic Education, a vital not-for-profit organization dedicated to understanding how photography matters in the world.