María Wills Londoño (Colombia) is a researcher and exhibition curator whose principal areas of expertise are the unstable nature of the contemporary image and innovative points of view of the urban face of Latin America. Her exhibition projects have been presented at the International Center of Photography in New York, the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris, Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid (PHotoESPAÑA), the Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City, and the Museo de Arte del Banco de la República in Bogotá, at which she was also responsible for temporary exhibitions from 2009 to 2014. She was curator of the exhibitions Pulsions urbaines (at the Rencontres d’Arles, in 2017) and Oscar Muñoz. Photographies (Jeu de Paume in Paris and the Museo de Ar te Latinoamericano in Buenos Aires, from 2011 to 2013) and co-artistic director of ARCO Colombia 2015. In 2018, she developed a research and exhibition project, The Art of Disobedience, a recontextualization of the collection of the Museo de Ar te Moderno in Bogotá. She founded and was director until 2018 of the Visionarios program, with the mission of highlighting the essential figures in Colombian conceptual art, at the Instituto de Visión.

An interview by Jacques Doyon

JD: You’re a researcher and curator of contemporary art exhibitions. You’ve developed a specific interest in photographic images and in Latin American art, and you’ve organized a large number of exhibition projects produced in collaboration with major institutions in Europe and North America, as well as in Colombia, where you live. It seems that you’re also quite familiar with the Montreal scene. Could you give an overview of your career and your ongoing concerns, and discuss how they have fed into this edition of MOMENTA 2019?

MWL: I think that my professional experience, independent of regional questions, has given me a broad comprehension of art processes. As both a professional and a spectator, I’ve had an opportunity to visit museums and spaces devoted to contemporary works, particularly those that offer an understanding of the complexity of today’s art beyond traditional media and formats. What I appreciate the most about this edition of MOMENTA, which I curated in collaboration with the biennale’s executive director, Audrey Genois, and its executive and curatorial assistant, Maude Johnson, is the focus on comprehension of the image beyond photography. Envisaged in the context of contemporary art, photography as a medium is understood, rather, through a diversity of points of view and formats. Today, it is a channel for raising questions not only about photography itself but about the world – a world that is in a crisis of reality and truth.

My career and experience have led me to explore the coexistence of the image as document and the image freed of photographic conventions so that it becomes amorphous and turns into video or sculpture. My first curating project, at the Museo de Arte del Banco de la República, was Re(cámaras): espacios extendidos para la fotografia (Re[camera]: Extended Spaces for Photography). From then on, I wanted to apprehend photography as an open field. The Life of Things (the title I proposed for the biennale) was inspired by various art practices that I saw all over the place, and certainly in Montreal during my professional visit to the 2017 edition of the biennale. But it’s also a project inspired by film and by literature – books by Orhan Pamuk (The Museum of Innocence) and Georges Perec (Les Choses), who explore humans’ relationships with objects. So, I wanted to create a project that would deal with the tensions that mark how we relate to the things that surround us today. On the one hand, we adore and fetishize objects: we create our lives around them and value them to the point that they transform our identities. We become people narrated by objects, through the stories about our lives that they carry. On the other hand, paradoxically, we have created a society that consumes and destroys: objects are trivial and part of an imperfect circulation of things that has led to the environmental crisis in which we are currently submerged.

JD: The theme that you propose this year invites us to take an interest in the life of things and how we represent them. More than simply reflecting a given reality, images help to shape our perception of objects and our interactions with them. And images are, themselves, things inscribed in a world with their own logic and effectiveness (you even speak of agency). It is the representation of this world of objects that you propose to explore from four angles (material culture, thingification, the absurd, and the environmental crisis) in two main exhibitions and fifteen complementary shows. What are the general thrusts of your investigation into the presence of objects in our lives and in contemporary society? How have you structured the exhibition path and the groupings of works?

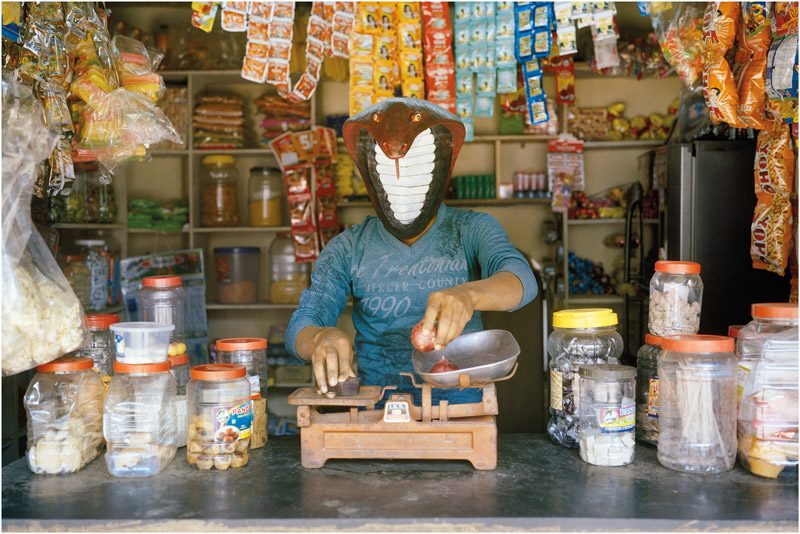

MWL: I align myself with the thought of James Elkins, who speaks of objects that look at us in their turn. The objects that surround us are full of stories about how we live. They tell us about the rigidity of historical discourses in “rational” societies, in which the focus on objectivity erases all subjectivity and leads to definitive statements rather than plural narratives. In The Life of Things, our main goal is to free ourselves from these discourses by, among other things, casting a critical eye upon the exaltation linked to “exotic” objects and recognizing the value of the handmade, knowhow, and traditions in daily life – though without falling into an ethnographic approach. We hope to revisit the image in light of postcolonial issues to present, for example, the work of native cultures or, in the case of Latin America, our indigenous cultures. We are interested, among other things, in the ways in which many artists apprehend the object without any form of hierarchy between living and non-living. Artists such as Raphaëlle de Groot, Laura Huertas Millán, and Jeneen Frei Njootli offer different perspectives on the systems and relations that we maintain with things. I am also interested in examining the psychological weight of the object, from the point of view of the reification of the human body that seems to have caused our lives to have lost importance, as the body’s functionality seems to be replaced by objects. Whence our interest in agency, the absurd “life” of the performative object or of the body, which, in its attempts to become object, flirts with madness. For this angle, I draw inspiration from surrealism.

The objects that surround us are full of stories about how we live. They tell us about the rigidity of historical discourses in “rational” societies, in which the focus on objectivity erases all subjectivity and leads to definitive statements rather than plural narratives.

One of my starting points was to address the object as something absolutely political, not solely as an element of representation. At first, I was interested in the still life as an art genre, because presenting objects in the seventeenth century according to the codes for this pictorial grouping involved a series of political questions. But beyond that, for me The Life of Things is a quest to understand that our actions have an immense impact on our environment; thus, the French-language term for still life, nature morte (literally, dead nature) applies to the current environmental crisis.

These questions are addressed through the four thematic components that you mentioned. The central exhibition, in two venues, will deal with the absurd in relation to the problems of the environmental crisis and with thingification in relation to material culture. With this cross-fertilization, without having discussed it beforehand, we ended up having highly effective exhibitions.

JD: Other questions also arise in this year’s program, which has a decidedly more political scope than might appear at first glance. These issues are linked, notably, to the place of women in the art world (with almost 70 percent women in the program), non-Western cultures, and, more generally, the relations of domination and power in society, as they are expressed in the world of objects around us. How can attention to objects and the way we represent them be useful in the face of these issues? What alternatives can art propose to the structural forms of domination and power?

MWL: I think that I gave part of the answer above, so I want to concentrate here on responding to the question about gender. In the culture to which I belong, the female body bears a huge amount of symbolic weight. For this reason, I feel that the question of objectification, modification, or reification of the female body must be radically investigated and, above all, recounted by female voices. It is a crucial aspect of the biennale to create a space for women contemporary artists who address the subject of the body, and if they unveil it (or don’t), it is in the form not of victim of a consumer society but of appropriator of autonomy and rebel power.

The multiple points of view that are non-Western, decolonial, queer, and others are bringing essential changes to how we understand images (which have been strongly linked to the Western and patriarchal history of photography). From this angle, I recommend seeing the projects by Alinka Echeverría, Karen Paulina Biswell, and Ana Mendieta. However, it’s not just about being female. In my answer to the previous question, I spoke about the rigidity of historical discourses, into which we are interposing images by queer and non-binary people; for example, Laura Aguilar and Victoria Sin challenge feminine ideals and pre-established roles. I believe that this type of proposal is essential for visualizing realities that are too often regarded as “other,” excluded from discourses and narratives. Alterity is always deeply rooted in the collective unconscious. In this respect, I also think that it is essential to mention Jonathas de Andrade’s project Eu, Mestiço, in which he critically addresses the construction of racial identities in Brazil based on a UNESCO study, offering a reflection on the dangers of recognizing differences as rigid questions.

JD: The question of anchoring the biennale in its own community is also important. It is always somewhat of a challenge for a foreign curator, given the amount of time it takes to travel to do research. It seems that MOMENTA innovated this year on the programming level by developing a closer collaboration among the curator, the executive director, and the executive and curatorial assistant. Can you speak about how the program was enhanced by the composition of this trio of professionals?

MWL: The theme “The Life of Things” is an idea that I developed following my visit to MOMENTA 2017 and my discovery of the Canadian art scene. I was looking for a theme that would be inspiring and poetic and at the same time would encompass the societal issues that I wanted to address. The collaboration was a way of pooling our research and artistic discoveries. Because an independent curator’s work can sometimes be quite solitary, the exchange of ideas enriched my curatorial approach and grounded it firmly in the current concerns of Canadian contemporary-art circles. Audrey and Maude are very familiar with this art scene, and they introduced me to the wealth of art practices in Canada. We wanted, for this edition, to offer exhibition venues projects that would be relevant and specific to their respective mandates. For example, Celia Perrin Sidarous will work from the collections of decorative arts and textiles at the McCord Museum, and Alinka Echeverría will present a corpus of works at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in which she explores representation of the female body in early photography. Under the theme “The Life of Things,” I thought it would be interesting to think about the life of objects once they enter the museum. Even if they are taken out of their original context, they still bear the weight of history – of their histories. The ghostly, haunted aspect of objects, related to questions of handling and traces, interests me greatly. There’s no doubt that this attention to the matching of venue and artist will contribute to the strength of the projects presented.

Translated by Käthe Roth

Jacques Doyon is editor-in-chief and director of Ciel variable.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 112 – COLLECTIONS REVISITED ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: María Wills Londoño, MOMENTA 2019: The Life of Things — Jacques Doyon ]