[Spring 2005]

Whether stills enlivened through video animation techniques, video loops upturned to approximate the live streaming of camera obscura technology, or satellite renderings rolled, spun and videotaped to mimic the rotation of the earth, Anzai’s artworks use illusion decisively and heavy-handedly, as they seek a renewed and more purposeful relationship between the viewer, the world and the picture.

by Cheryl Simon

No one image can replace the intuition of duration, but many diverse images, borrowed from very diverse orders of things, may, by the convergence of their action, direct consciousness to the point where there is a certain intuition to be seized.

⎯Henri Bergson1

Tetsuomi Anzai’s mixed-media installation works orchestrate unique perceptual experiences by borrowing diverse images from very diverse orders of things. A veritable poetics of photo-based form, his monitored video loops, regular and camera obscura-type video projections, video animations, and traditional, pinhole, and pseudo-satellite photographs are combined and arranged according to the intuitive effect generated by the convergence of the different formal characteristics and temporal principles of each medium.

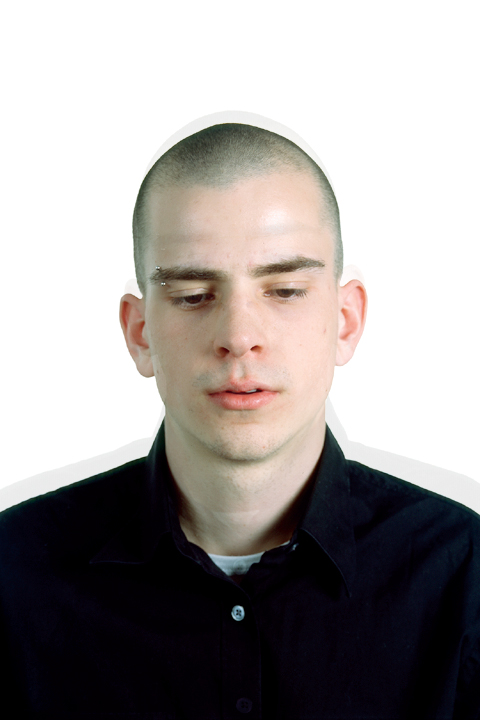

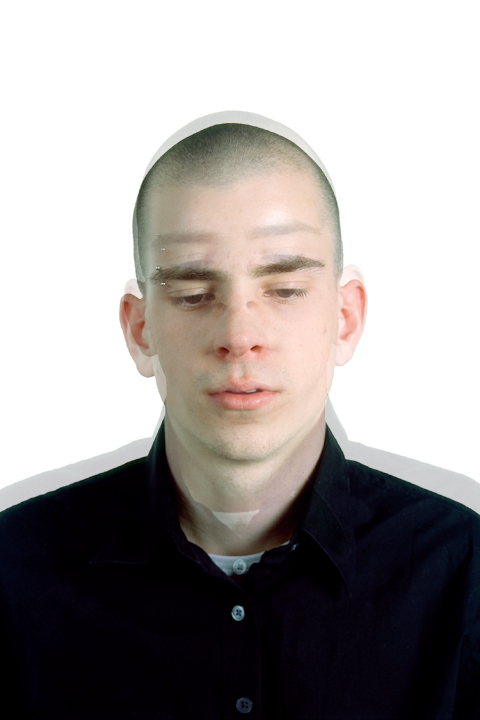

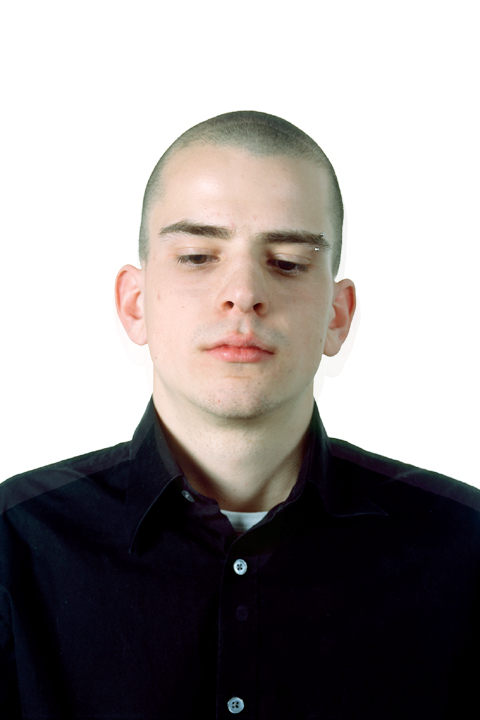

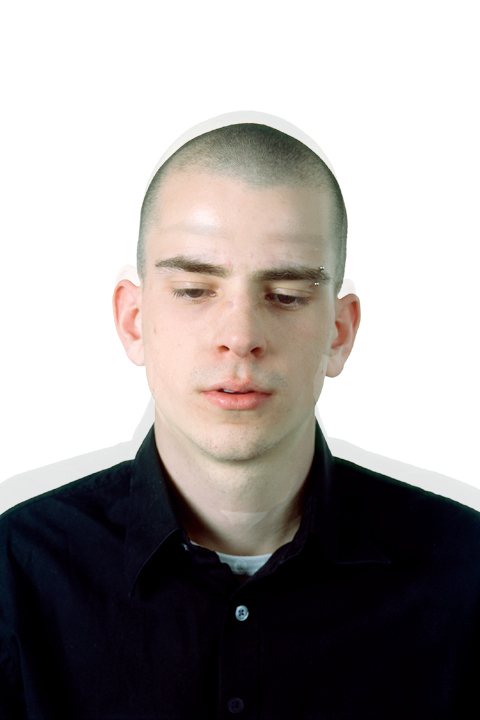

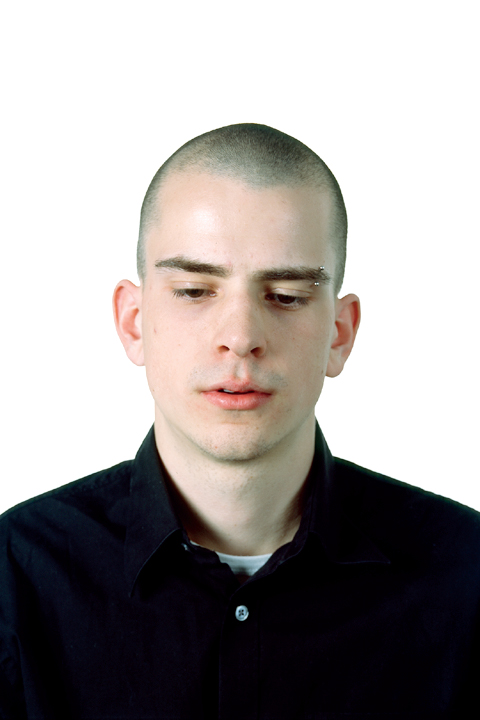

With Kokyu (2003), Anzai’s series of large-scale video portrait projections, consciousness is achieved by way of an illusion. We first meet his portrait subjects at the end of a darkened corridor – large-scale, full-frontal video projections of individuals whose only actions consist of the inhalation and exhalation of breath. The framing, combined with the subtle movements and even subtler flickering of the video signal from which these subjects emerge, invites comparisons with works produced in the flourishing genre of extended-time video portraiture.2 While movement in Anzai’s portraits is equally subtle as it is in any other work of this type, its temporal character is clearly different. Defined by the regular breathing of these portraits’ subjects, the rhythmic repetition of action is more coordinated than the twinges and spasms one finds in a subject bearing still and enduring scrutiny over an extended period of time. In fact, the movement in Kokyu appears more routine than one might imagine even of this particular approach to video portraiture. In reality, the movement here is not continuous but achieved through the animation of two still photographic images taken at peak moments during the breathing cycle, repeated, slowed, looped, and presented via video projection.

Here, the perfect beat of repetition encapsulates the mechanical reproduction process of photography and lends the work a sense of temporality particular to the photographic experience – a technology and temporality very different from that conjured by the raw vitality of the flickering field of electronic video light. Summoned together, these modes of mediation have a past and a present, soliciting both habitual and instantaneous responses to the visual stimuli, and so offering an ideal illustration of the orders of perceptual processes at work in active modes of consciousness. Although there’s no real continuous time in this picture’s recording, there is a real-time effect achieved in the viewing. The steady, regular tempo encourages action in kind, an action qualified and modified by the glittering “noise” of the video projection as it enlivens the reverberations. Repetition and anticipation petition the subject in equal measure so that each aspect of this particular image repertoire shapes the viewing experience in its own way, synergistically creating a familiar yet ultimately dynamic connection between viewers and view, the world and the picture.

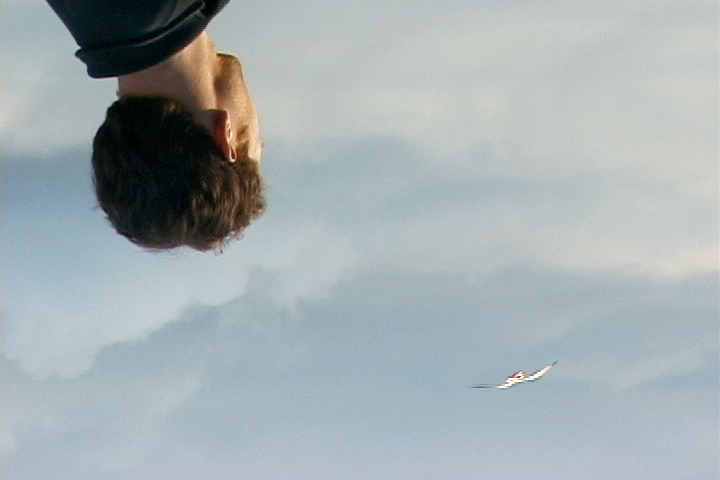

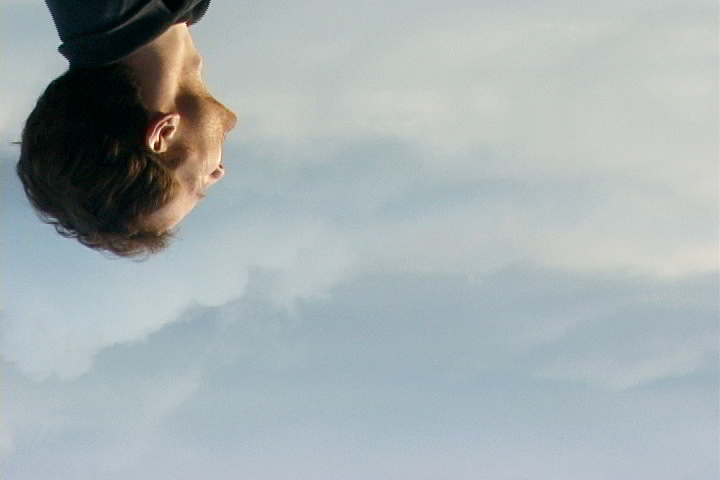

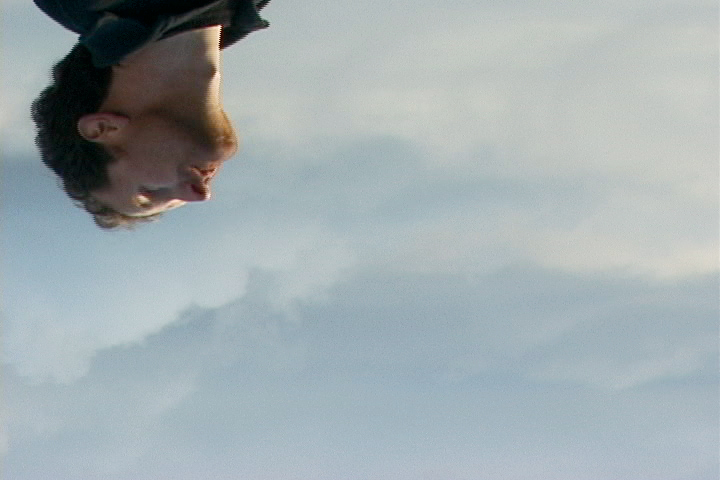

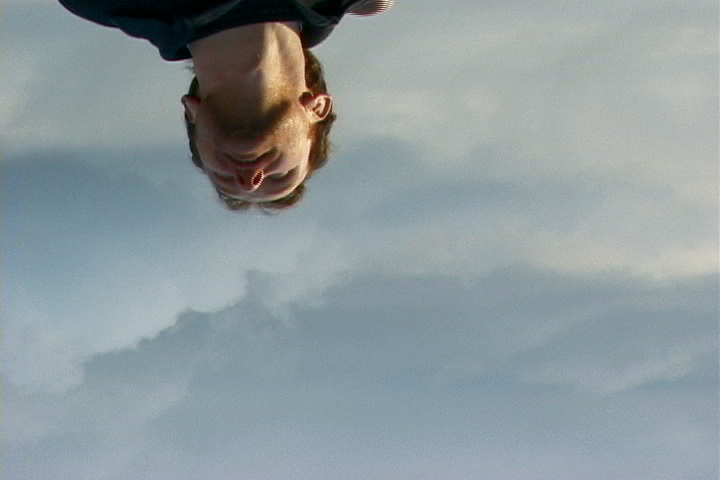

More directly engaged with questions of perspective in the relationship of worldview and picture, The Other Side (2004) adds another level of reference to Anzai’s technological universe. Approximating the inverted viewpoint of a camera obscura image, the installation places an upside-down video-stream projection depicting the heads of people moving across an empty sky above a still “pinhole” panorama of the Vancouver Airport. At the end of the twelve-minute tape, one of the walkers look toward the airport landscape – looking up from his perspective but down from ours – suggesting the possibility of a link, or even a convergence, between the two spatially and temporally distinct images.

Significantly, the worlds represented in The Other Side are not only uninhabitable and non-navigable but irreconcilable in this situation. Devoid of gravity, the “other side” may be “alive” with the energy of continuous time, but it has no grounding in the here and now. Likewise, the soft-edged pinhole image might offer a concrete site and evidence of stability, but it is static and devoid of vitality. It is significant, too, that Anzai has separated the still and moving imagery here. Coupled with the spatial disorientation of the upturned image, this partition works to underscore the different temporal dimensions of these two technologies, and so positions the perceiving subject in between here and there, then and now – travelling through space, in the flux of time.

Anzai explains the purpose of inversion in his work with reference to Rodney Graham’s Millennial Time Machine, also a camera obscura work: “Where Graham’s works use the camera obscura as a machine that could take you back in time, I was interested in the idea of a camera obscura that could take you to the other side of the world.”3 A proto-photographic form, the technology shrinks space as it focuses objects at a distance onto a closer plane. Unlike photography, the camera obscura illustrates movement and temporality without fixing it. And, as Jonathan Crary has observed, it is this ability to preserve the vitality of an external world rather than its capacity to define the subject through linear perspective that fascinates the viewer, aligning the technology with techniques of illusion and magic, as readily as procedures of representation.4

Exploiting this sense of wonderment and mixing in some awe, The Infinite Plane (2005) presents a series of still and moving “camera obscura” projections of satellite imagery. As with Kokyu, movement here is produced via illusion. Anzai’s “world” is made with a satellite-rendered earth map attached to a cylinder, spun on its axis and videotaped as if in slow rotation. Although the perspective that the viewer is invited to assume invites fantasies of omniscience, omnipotence, and control, this “God’s eye view” of the earth is very purposely skewed, distorted by the obvious levels of artifice involved in the production of the illusion.

Under the rubric of information communication technologies, imagery produced using different photo-based technologies is now considered “digital media” – just so much data – the effect of which is to obscure the material conditions of image production and risk losing sense of why these images matter to us. Anzai’s mixed-media art works to stem this tendency. With the most basic procedures and transparent illusions, the materiality of his imagery is “thickened” and so, too, are our perceptions of time enhanced and extended.

If our expectations of perspective and situation are upended and confused in Anzai’s work, so, too, are ideas of temporality and transformation. Here, still and moving picture technologies represent mechanically distinct but conceptually interdependent processes. Endlessly looped, the video component represents the perceptual paradox of consciousness. If the technology itself represents time as immediate and continuous, the video ends only to begin again at the same spot and from the same moment. Similarly, the still image is still only insofar as it represents a point in time from which experience is inaugurated and to which it returns. Finally, it is perspective that is necessary for transformation to take place. Change occurs not on the side of the image but on the side of the viewer whose awareness is renewed each time the image is perceived, re-presented and replayed.

Thanks to Jessica Auer, Alberic Aurteneche, Esther Choi, Sarah Ciurysek, Leigh Davis, Shaunna Dunn, Patrick Lunden, James McDougall, Sol Nagler, Clint Neufeld, Andreas Rutkauskas, Kim Simard, Justine Litynsky; graduate students in my Time seminar at Concordia University last winter. Their insightful thinking on time in media art has been inspiring and enlightening.

2 Fiona Tan’s work, included in this issue, offers an excellent example of the formal conventions and critical aspirations of the genre.

3 From an interview conducted in March of this year. See also Anzai’s review of Rodney Graham’s exhibition in this issue and http://www.belkin-gallery.ubc.ca/webpage/online/millennial.html for more on Graham’s camera obscura work.

4 Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer (Cambridge, MA, and London, England: MIT Press, 1992), pp. 33–37.

Originally from Vancouver, British Columbia, Tetsuomi Anzai studied photography at the Emily Carr Institute. He currently lives and works in Montreal, where he is completing an MFA at Concordia University. Using photography, video, sound, and installation, his artistic practice negotiates territories of dislocation and deracination in “a world already mapped”.

Cheryl Simon is an artist, academic, and curator whose current art and research interests include explorations of time in media arts and collecting and archival practices in contemporary art. She teaches in the MFA – Studio Arts program at Concordia University and in the Cinema + Communications Department of Dawson College, in Montreal.