[Spring 2006]

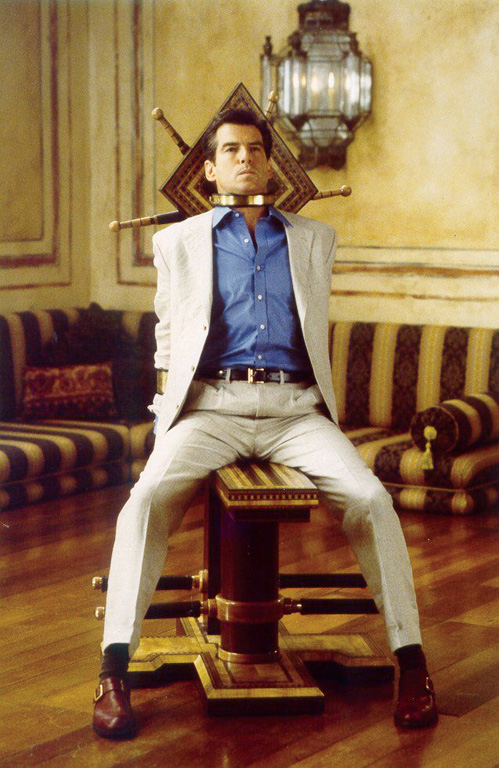

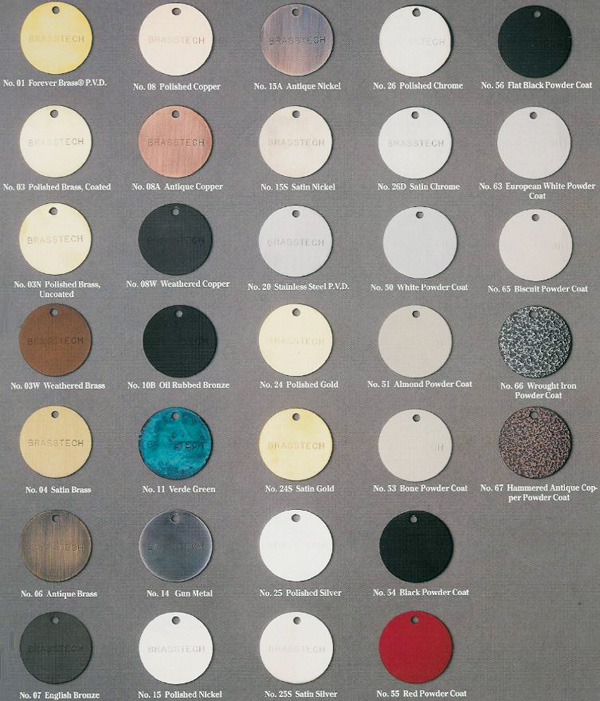

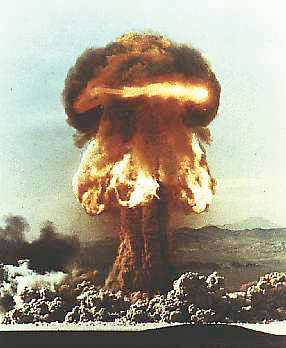

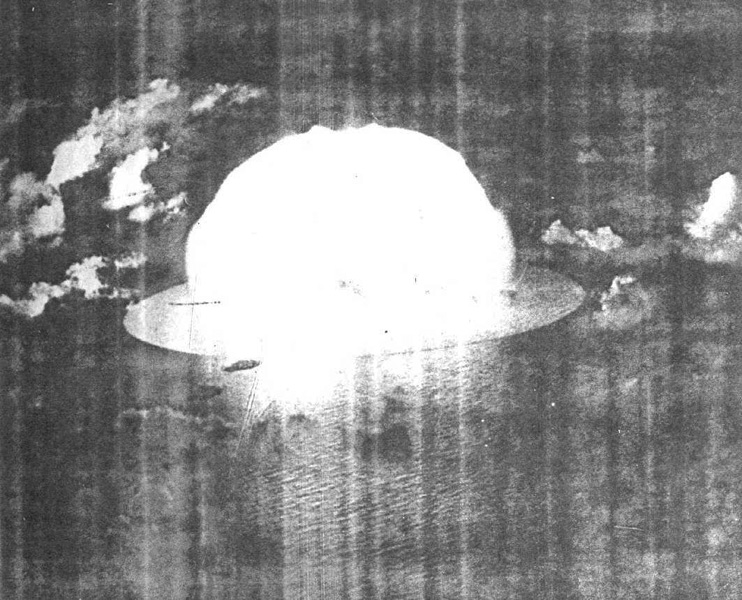

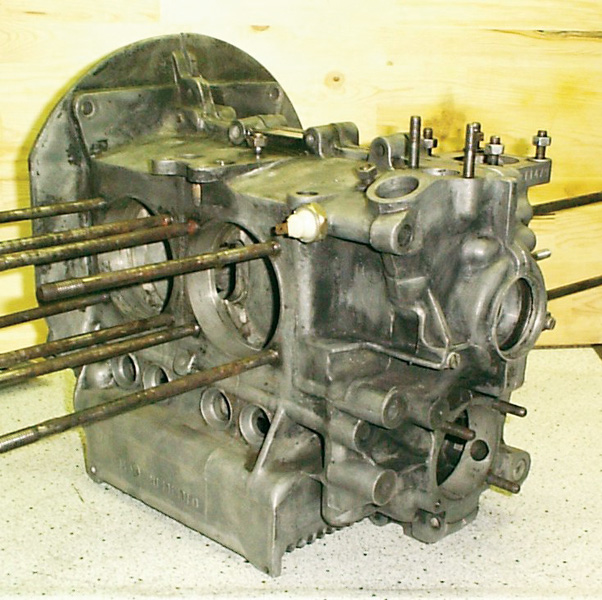

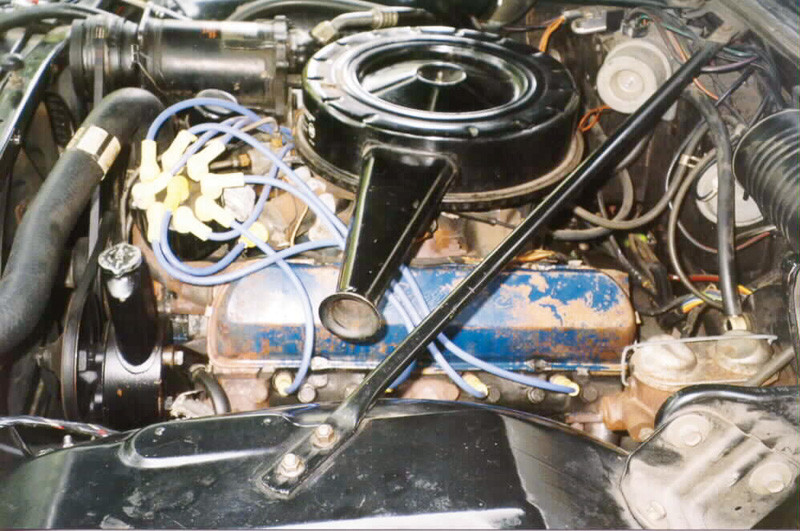

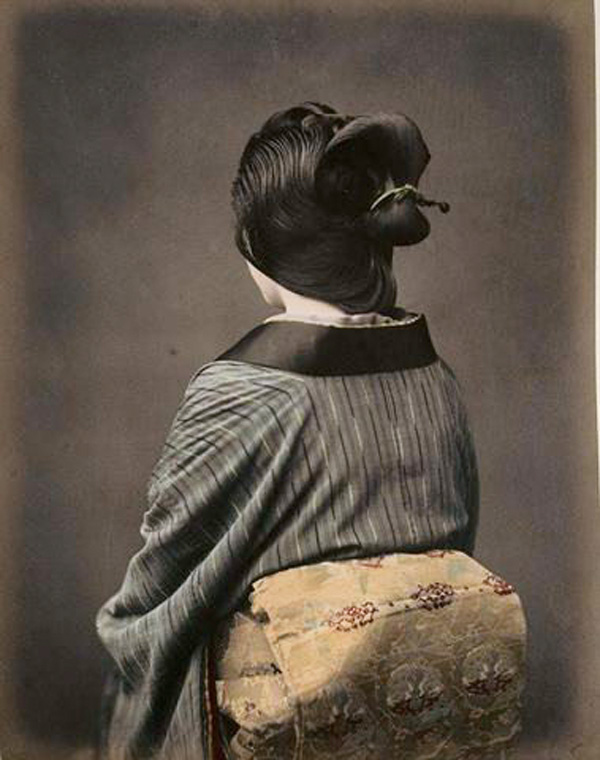

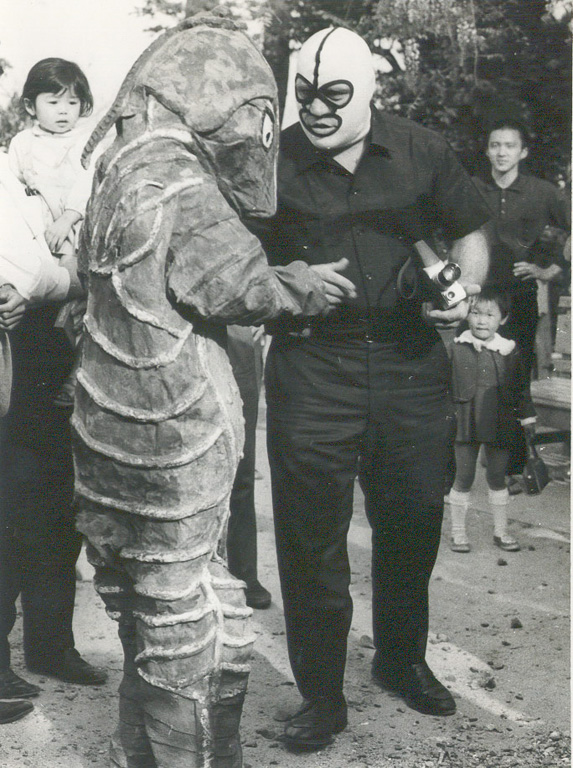

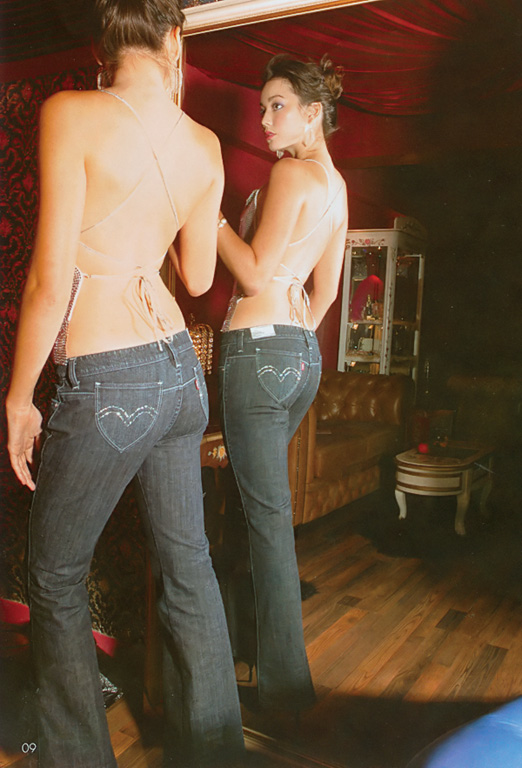

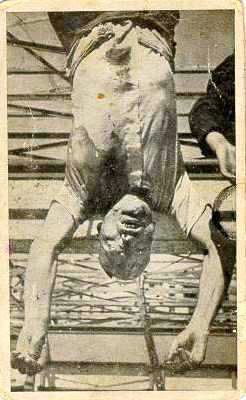

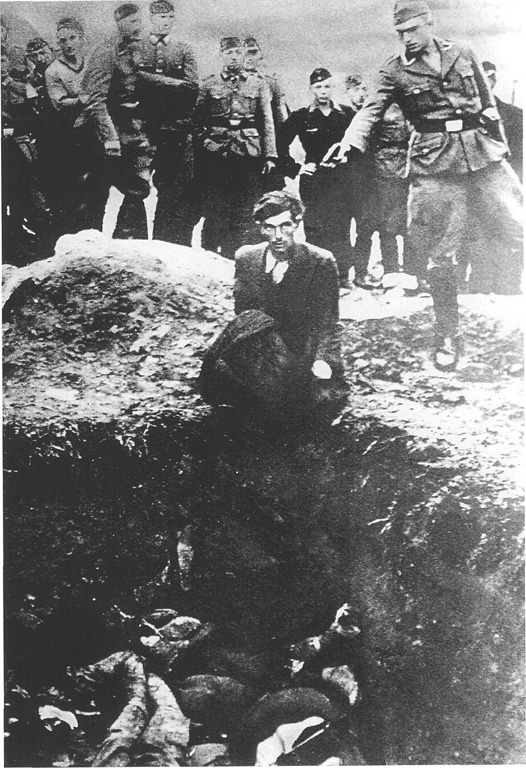

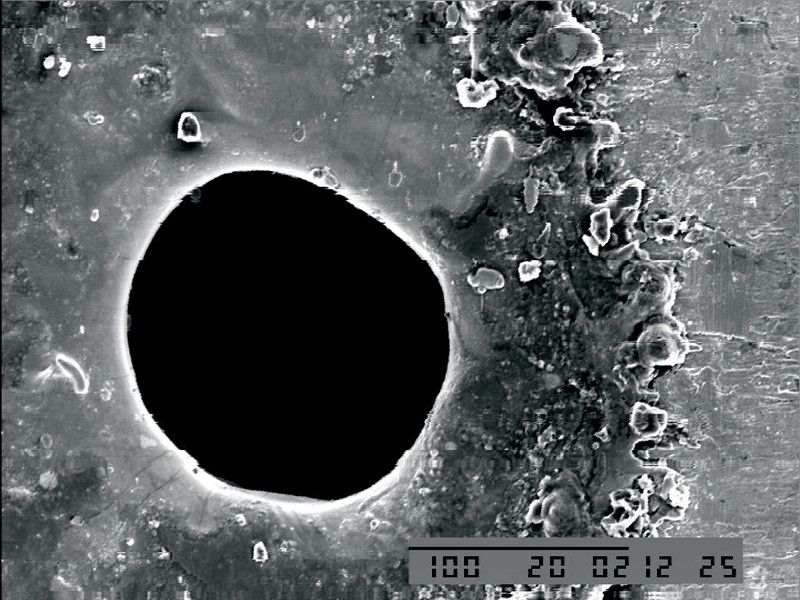

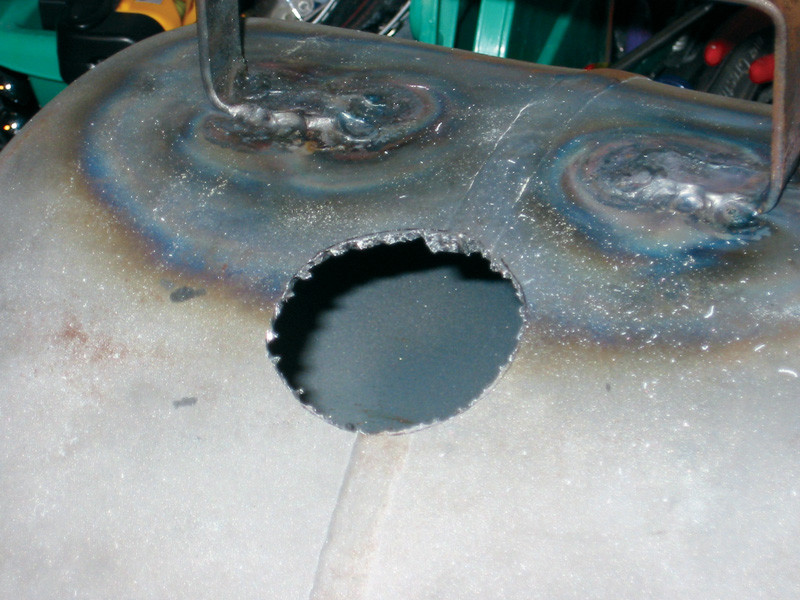

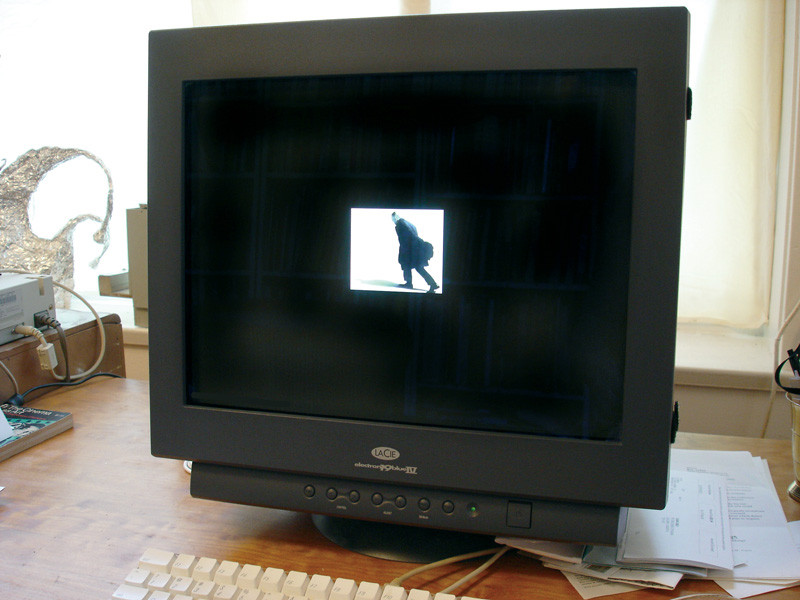

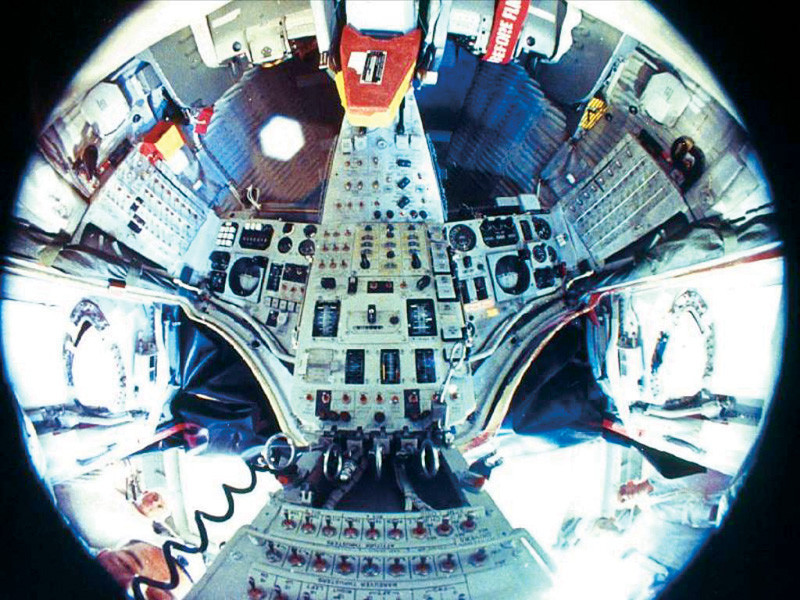

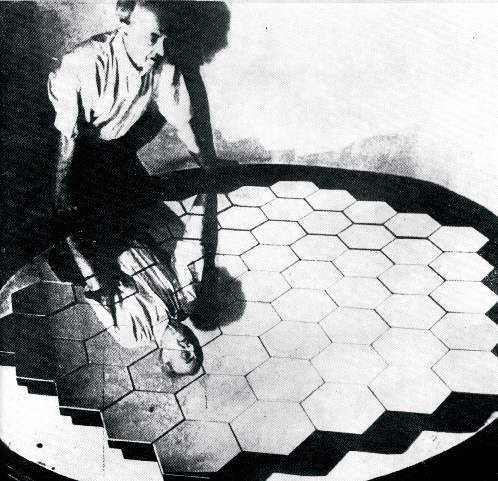

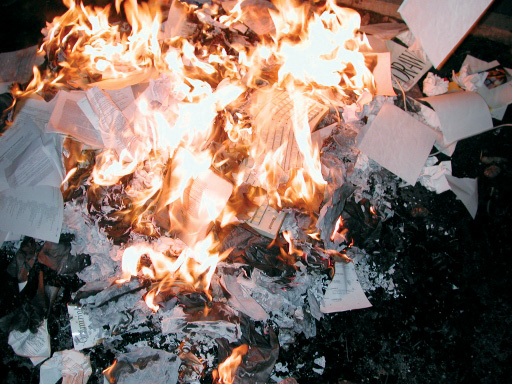

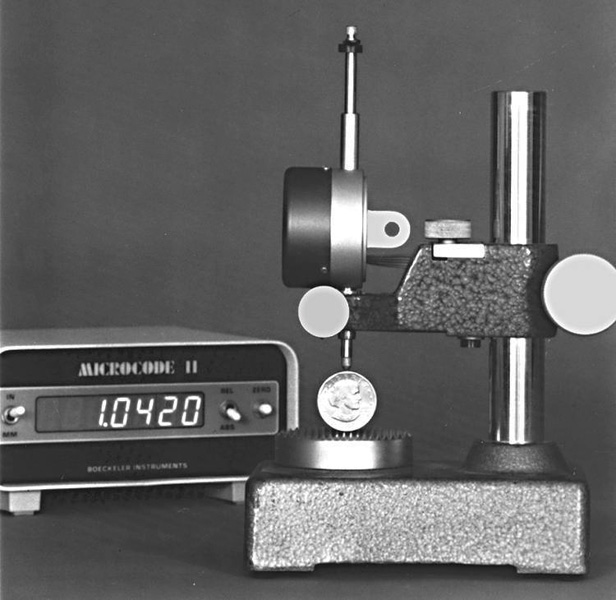

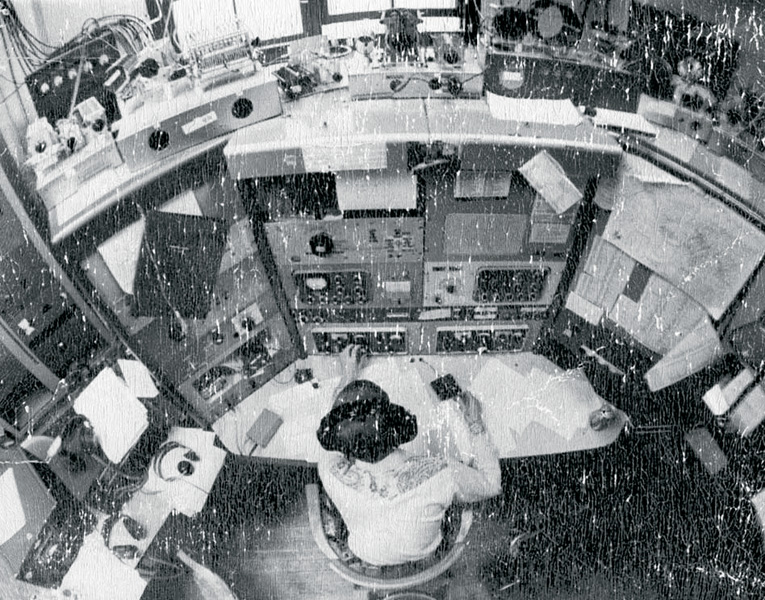

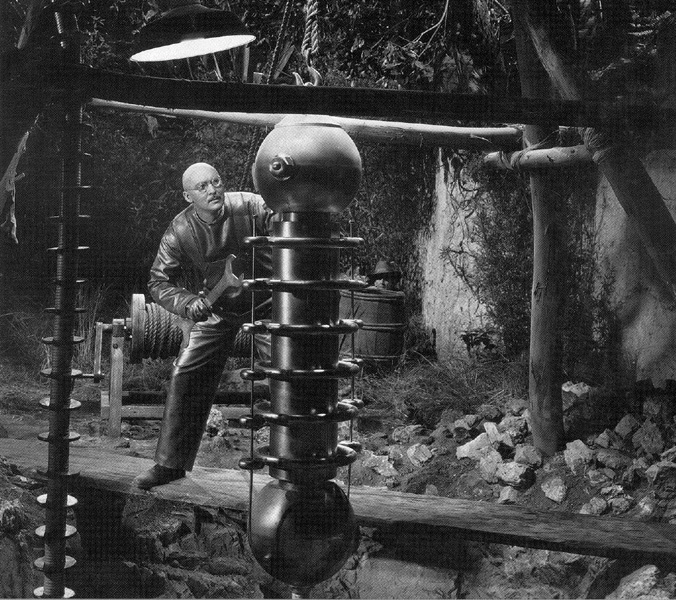

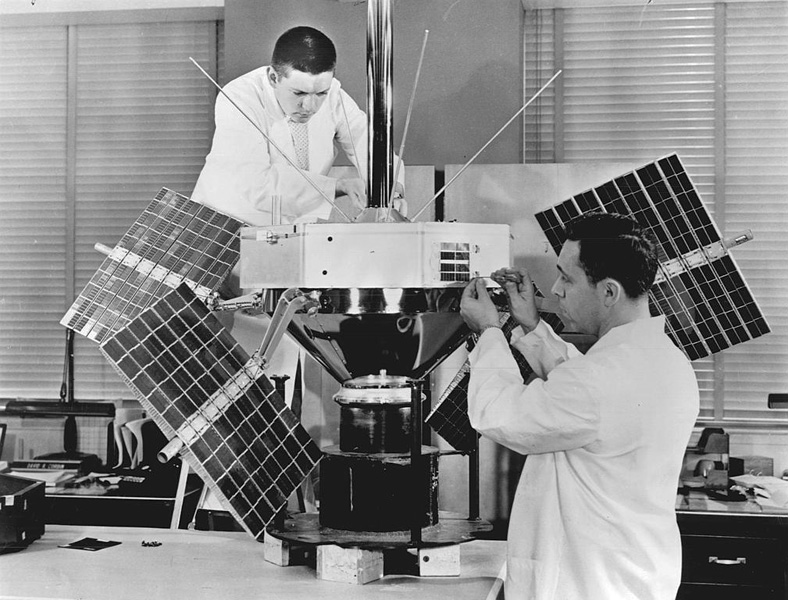

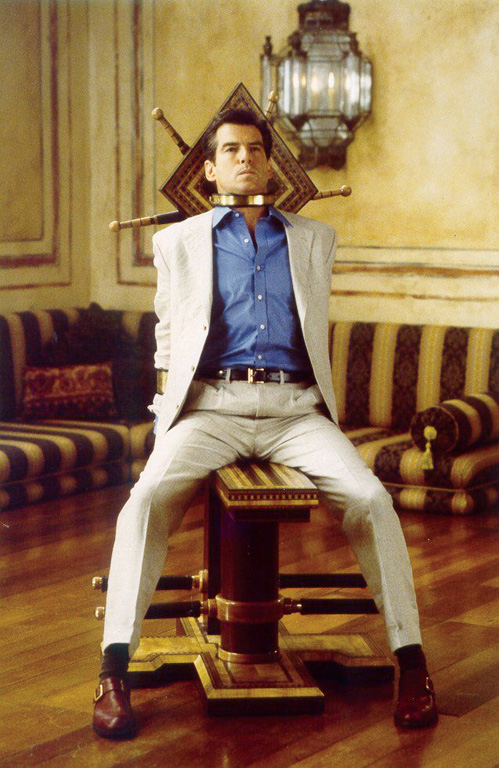

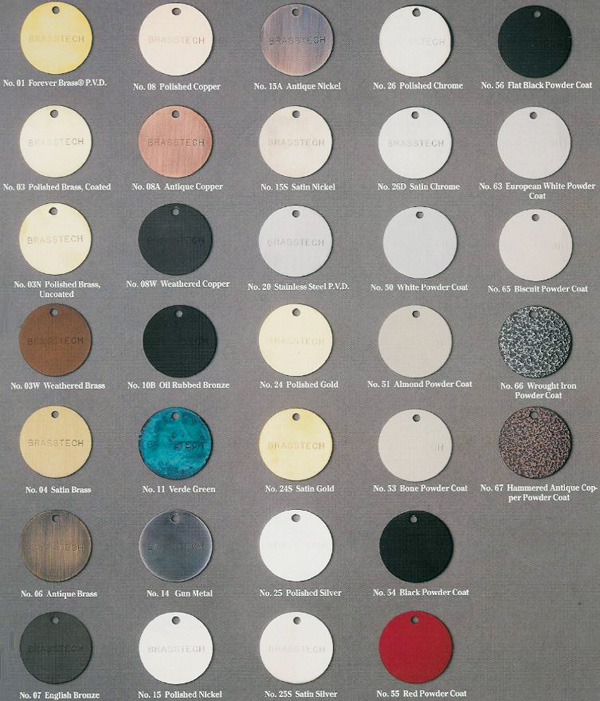

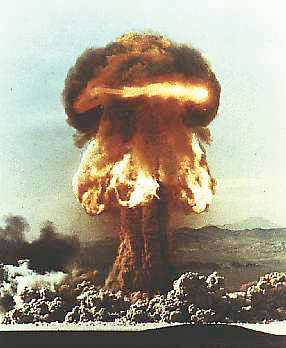

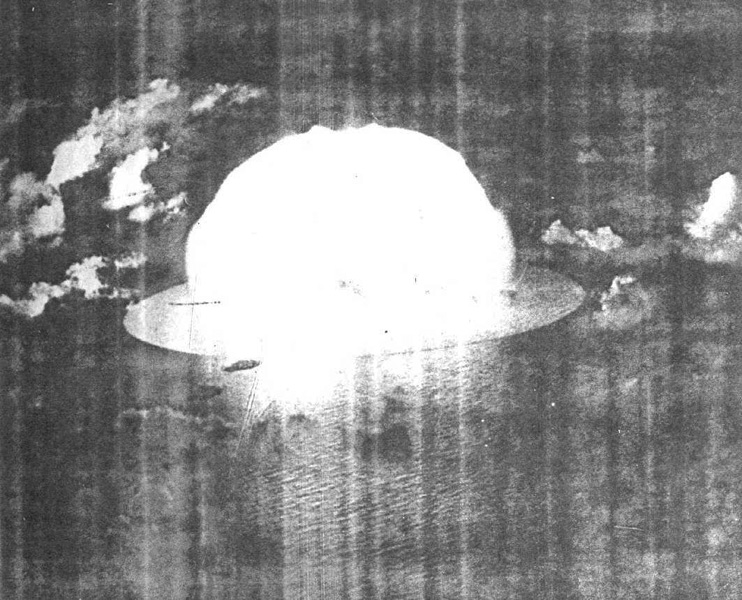

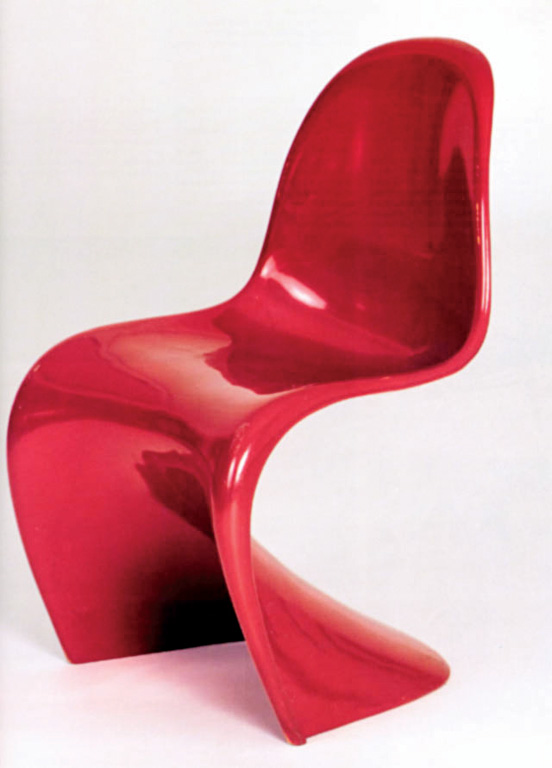

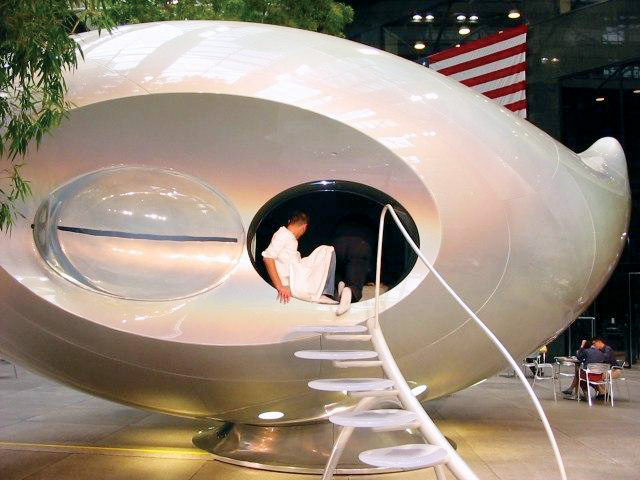

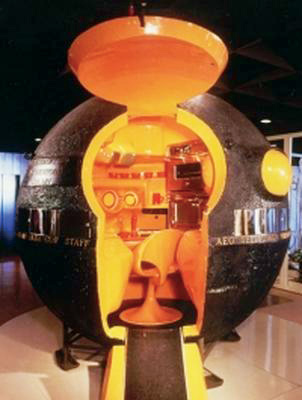

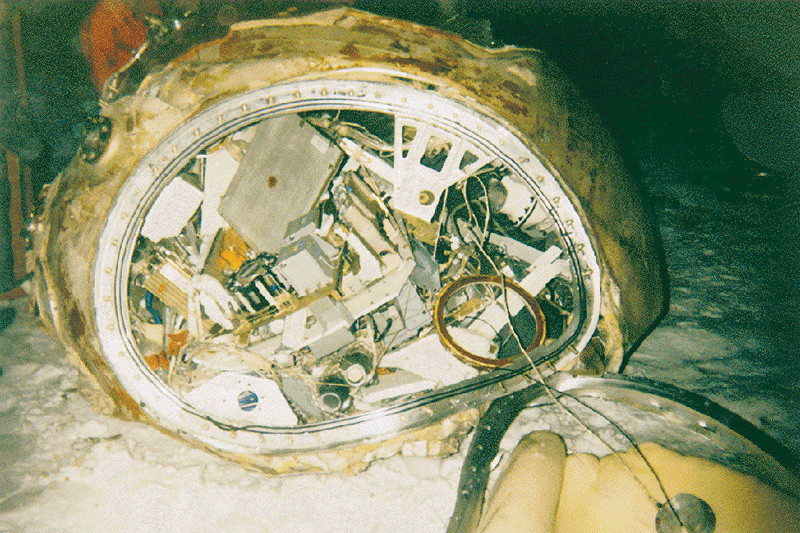

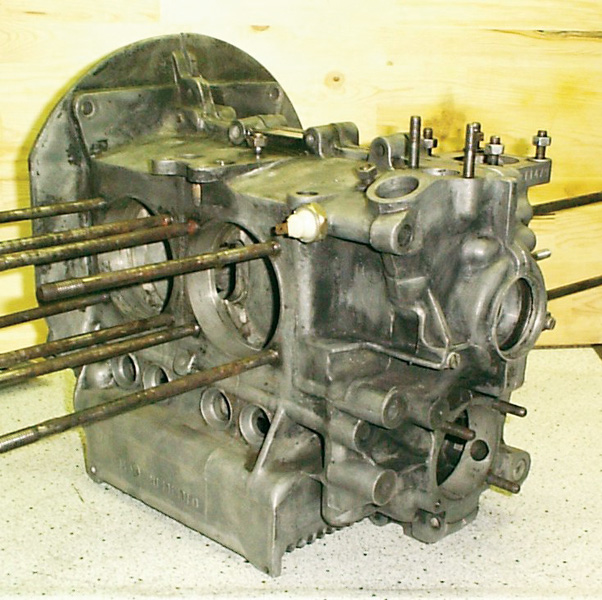

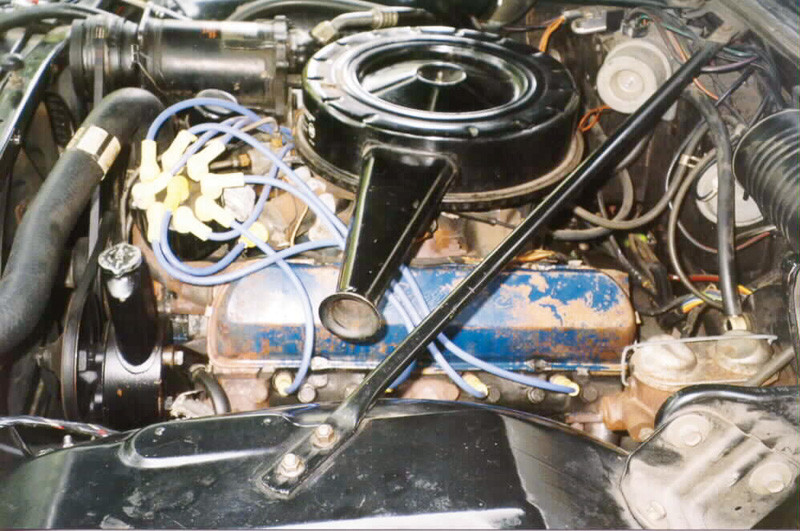

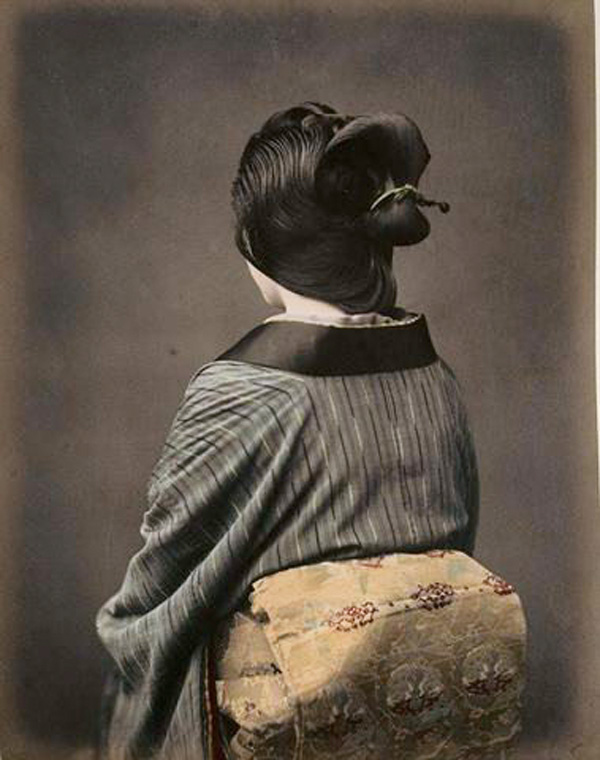

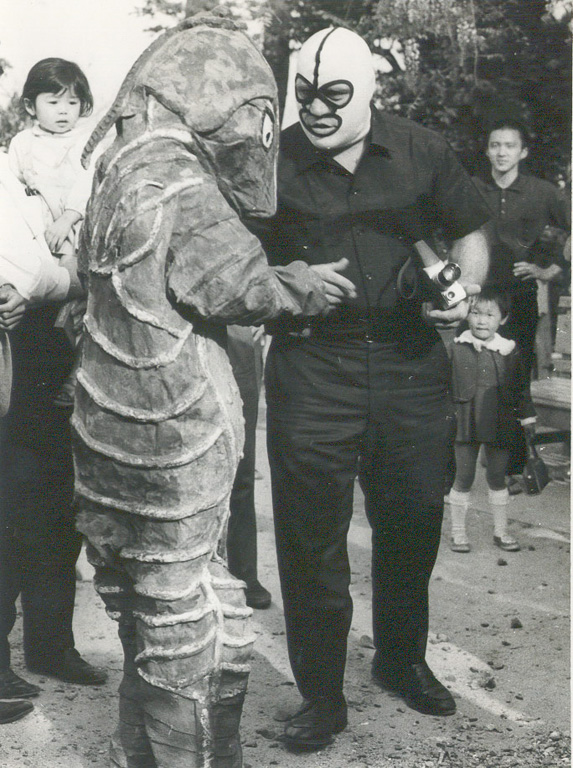

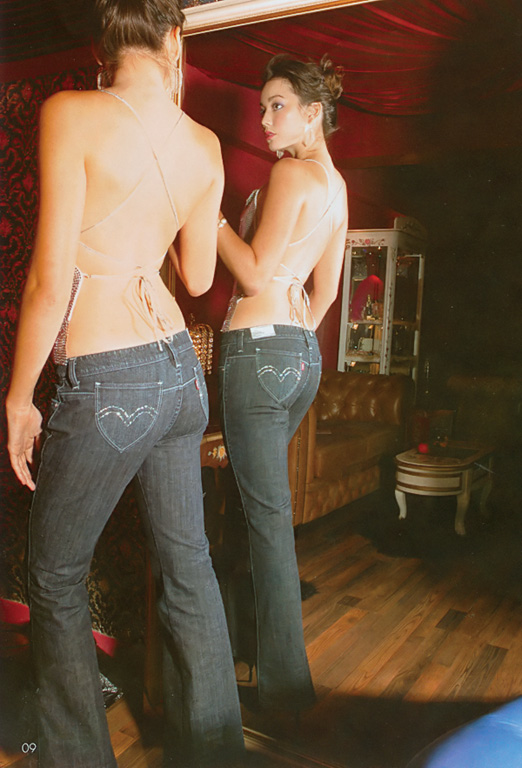

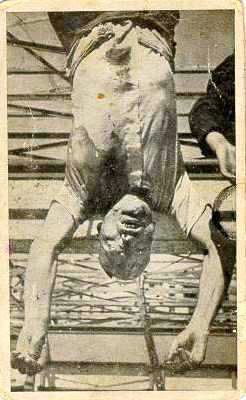

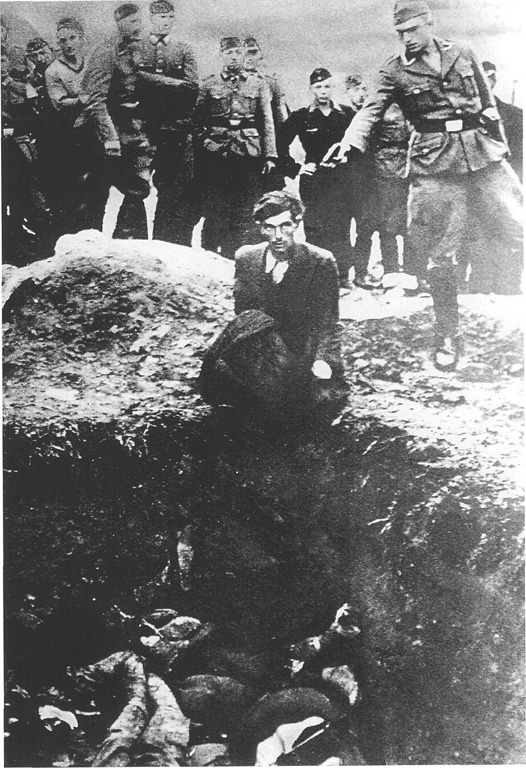

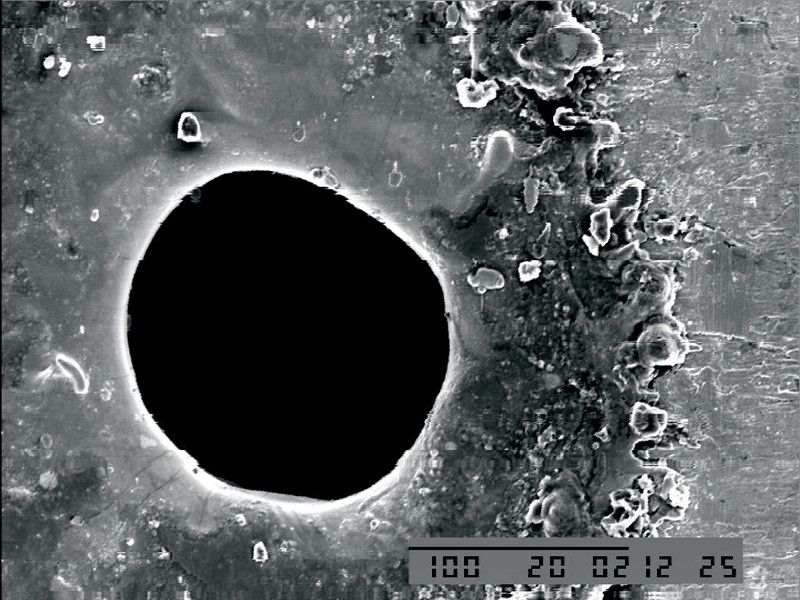

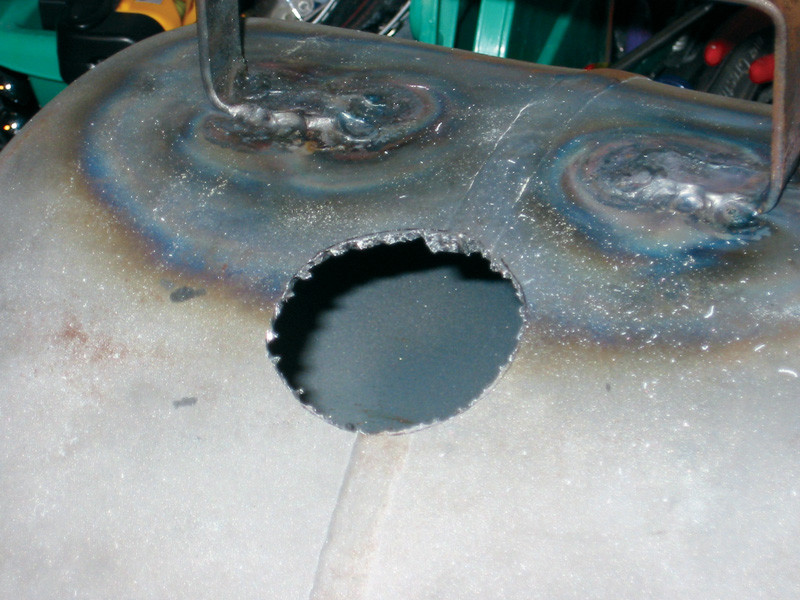

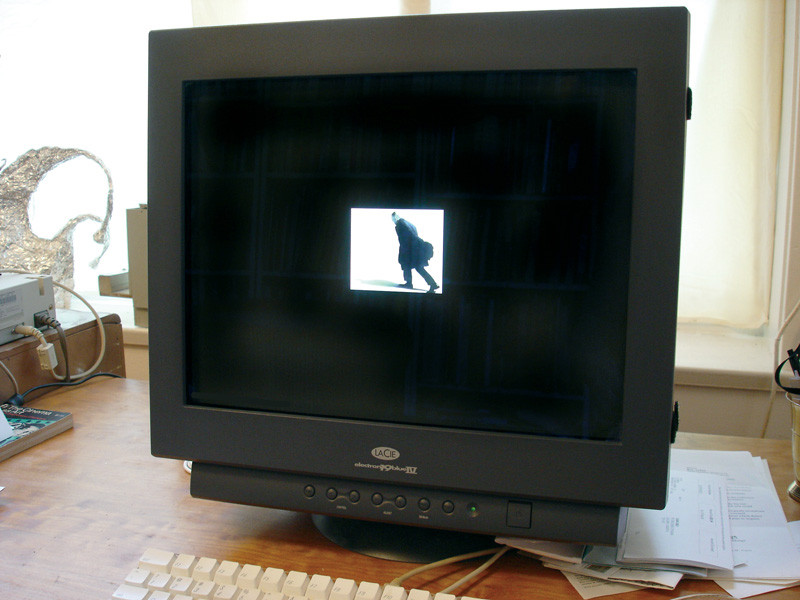

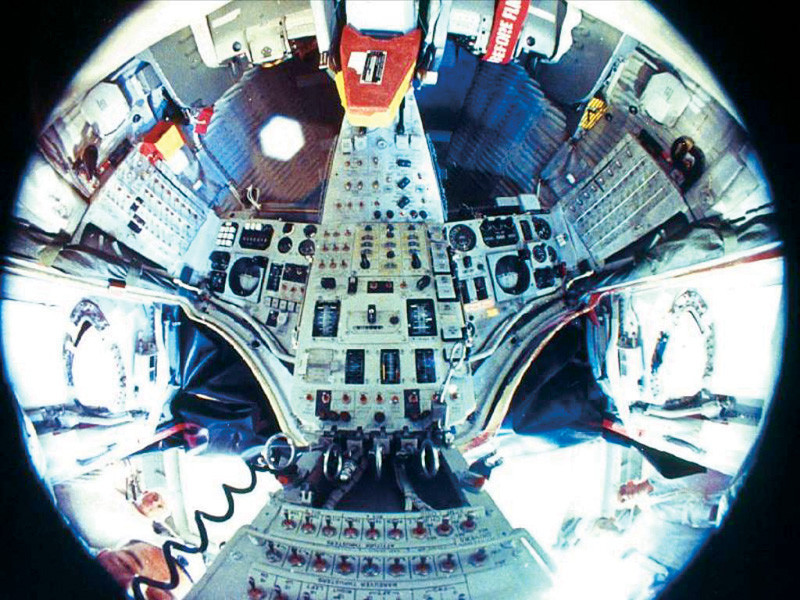

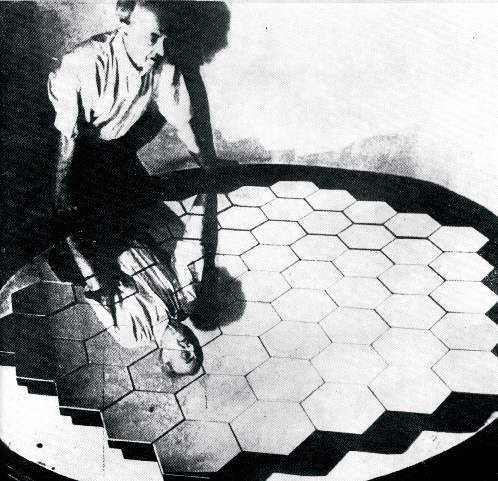

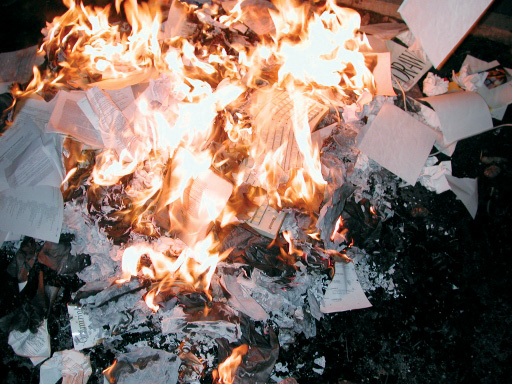

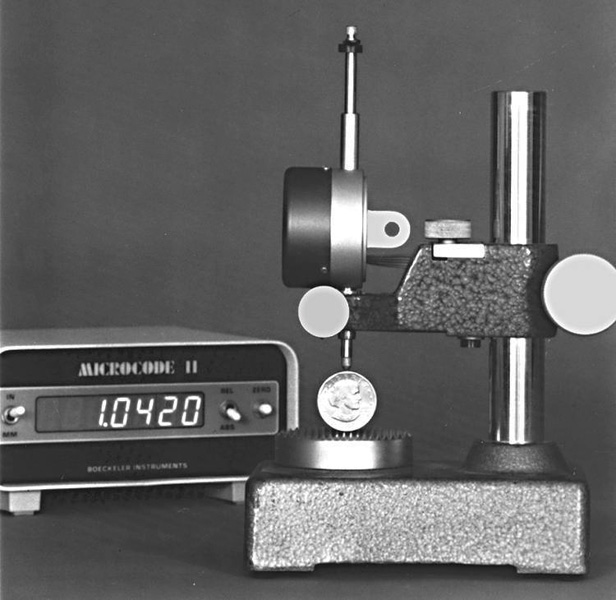

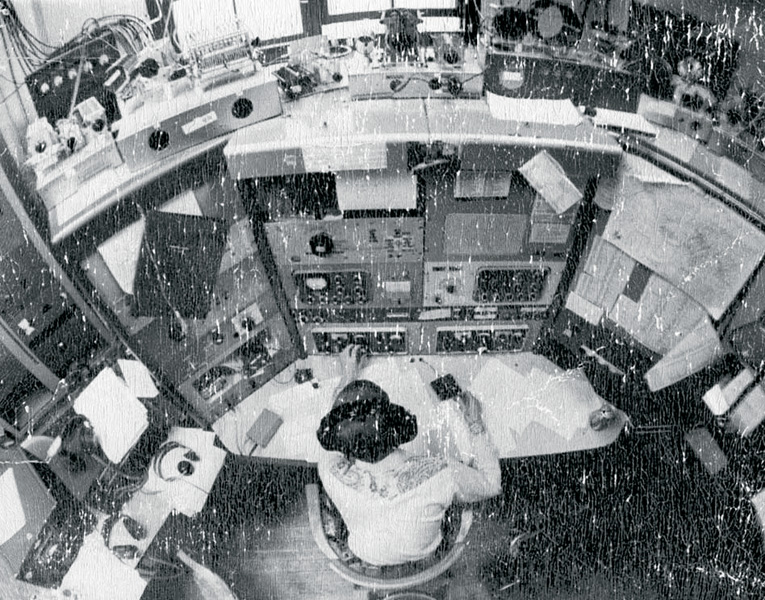

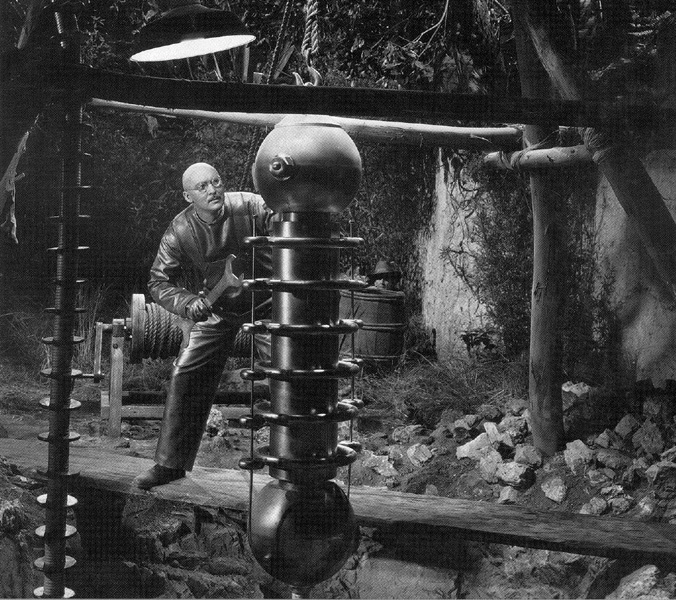

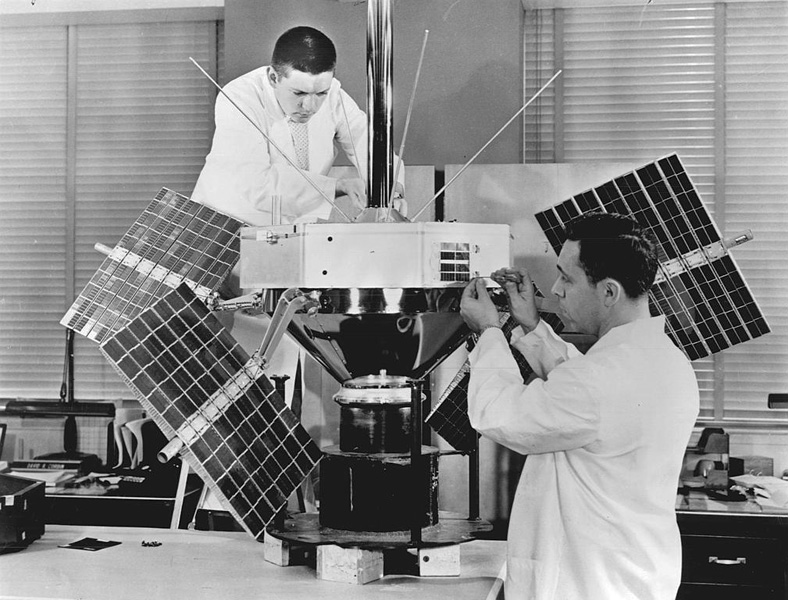

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

Roy Arden, The World as Will and Representation – Archive, 2004 - 10,000 successive images, 38 min. 51 sec. © Roy Arden

by Dieter Roelstraete

In The World as Will and Representation, his first-ever online/Internet art project, acclaimed Vancouver artist Roy Arden returns to the archival tropes, modes, and motifs that helped give decisive shape to his landmark works from the mid-1980s, the best known of which are the Rupture, Abjection, and Mission “series” or “suites.” In The World as Will and Representation, Arden returns both to the archive – with a vengeance indeed! – and to its implied imaginings of visual excess, its “archive fever.”1

“Appropriating” existing imagery instead of merely producing new images – together with Vancouver “photo-conceptualism,” the well-known 1980s strategy that was “appropriation art” (Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, Haim Steinbach; to a certain extent this category could also include Hans-Peter Feldman, an artist who exerted considerable influence over Arden) remains an important factor in locating and understanding Arden’s artistic practice. The immense, sprawling, encyclopedia-like work that is The World as Will and Representation consists of a psychedelic, alphabetically arranged avalanche of literally thousands of images (most of which, naturally, picked from the World Wide Web or Imagobahn) that unfolds like a delirious domino theory of an “other” world history or an “other” cosmology – one that is, of course, pace Arden’s unfaltering sense of the microscopic and micropolitical, infinitely more modest, sobering, and prosaic in tone than the grand theories and master discourses of canonical, capital-H history. It is an exercise in the taxonomy of difference and history-telling that brings to mind both the magical view of art as an “other” thought or a mode of “othering” – associative, analogous, allegorical, prone to “uncanny juxtapositions,” pseudo-scientific, and, last but certainly not least, parodic – and the critical theory–endorsed view of art as the melancholy science of “negative dialectics.”2 This epistemological posture, in fact (see note 4), is the exact point at which Arden’s work intersects most markedly with that of fellow Vancouver artist Steven Shearer, whose “archival works” – huge digital prints assembling a dizzying array of photographic images culled primarily from obscure Internet sources – deploy a similarly encyclopedic, all-encompassing tactic of “uncanny juxtaposition” as an inroad into art’s “other thought.” Much like Shearer’s archival works, Arden’s Web project shows artistic thought “at work” – that is, caught in the process of its “other” world-making or history-telling.3 In The World as Will and Representation, however, this process takes place at a dizzying speed, one that is in fact reminiscent of squads of neurons firing off signals, which, in the “real” world of neuroscience, constitutes thought as such. A torrential cavalcade of ten thousand images clocking in at just under forty minutes, Arden’s digital archive serves up more than six still images every second, causing the viewer to lose track rather quickly of the arcane ordering logic that underlies his shelving of the images in question – or, put another way, causing the viewer to look at the world rather differently: as Roy Arden’s will and representation.

“TWAWAR”: in appropriating the catchphrase-like title of the morose magnum opus of one of philosophy’s most enduring and intriguing figures, the inimitable Arthur Schopenhauer, Roy Arden – whose well-known and widely shown “suites” of photographic works such as Landscape of the Economy and Terminal City of course betray a keen eye for the unsavoury micro- or anti-histories that lie hidden beneath the layering of the many master narratives that together make up history and/or reality – inevitably subscribes to the bleak world-view that, back in the early decades of the nineteenth century, pitted the quarrelsome, cantankerous German philosopher against his contemporary, Hegel, whose humourlessly self-confident, optimistic belief in the teleology of Progress and Enlightenment would obviously prove – that is, in the short term: who’s to say who will be proven “right” in the longue durée? – the more influential philosophical doctrine.

Schopenhauer’s history of the world is a notably gloomy affair – and probably much closer to the truth (or so the news channel would have us believe) than the Hegelian fantasy of history’s march into the light; it shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that Arden’s sympathies, as those of a conscientious, scrupulous chronicler of despair (Abjection, ‘Locked Out’ Workers), dissent (Rupture, Supernatural), and loss (Eureka, Terminal City), lie with the Schopenhauerian program of suspicion and negation, and of dismantling the lofty claims of Enlightenment philosophy. Furthermore, the swirling vision of stasis and sameness that underlies Schopenhauer’s worldview (he was among the first to introduce “Oriental” concepts of circularity into Western philosophy, thus questioning the dogma of linearity and teleology that had been shaping Western thought since Aristotle4) famously presages the Nietzschean theory of eternal recurrence – and this in turn resonates rather paradigmatically with Arden’s caustic “vision” (“negative diagnostics”) of history as an eternal rerun of irresolvable dialectical tensions. Not coincidentally, the soundtrack to this database-like, encyclopedic project, which inevitably brings to mind Jorge Luis Borges’s famous jibe at the inherent absurdities of the very act of encyclopedic archiving,5 is taken from a classic example of righteous, soul-searching 1960s black music – Timmy Thomas’s heartfelt plea for peaceful “synthesis,” wholeness, and coexistence, “Why Can’t We Live Together,” a concise, matter-of-fact pop summary of Schopenhauer’s dismal existentialism if ever there was one. In Arden’s remix, however, the harrowing lyrics to Thomas’s epochal tune are never allowed to surface, and the song, much like the burning wheel of images that it accompanies, remains forever trapped in the organ-pumped circular motion of a chorale whose voices fail to materialize. We look on, dumbstruck and oblivious, as history unchains its fearsome powers of forgetting, with the clinical, slightly amused detachment of Arden’s diagnostic gaze: strangely, we find there is much disturbing beauty in this world’s wretched spectacle.

1. The reference here is to Jacques Derrida’s belated “Freudian impression,” Mal d’Archive, translated by Eric Prenowitz as Archive Fever (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996).2. See also my recently published essay “Negative Diagnostics: Vision and Discontent in the Work of Roy Arden,” in Roy Arden (Birmingham: Ikon Gallery, 2006).

3. In addition, both artists share a singular fascination for the netherworlds of “lumpen” or proletarian culture that is clearly (and significantly) not without its biographic overtones. Shearer’s archives teem with the ignoble emblems of “contemporary proletarian craft” or “blue collar folk culture,” most notably of the hard rock/heavy metal variety; Arden’s preoccupation with the fate of the proletariat – as a political force, but also as a cultural “locale” – is well documented and ranges from the historical Rupture series to the more recent ‘Locked Out’ Workers, Vancouver, B.C. (1994). In The World as Will and Representation, the base materialism of proletarian culture takes on an entirely different meaning, and “historical materialism” as the evangelical creed of proletarian politics is shown here as rooted in a refreshingly literal reading of materiality as a mere “matter of matter,” of “all kinds of stuff.”

4. In Arden’s The World as Will and Representation, the “Western” dogma/doxa of linear progress, and linearity as such, is mercilessly parodied in the faux-naif display of alphabetical orderliness in which the artist has accumulated his visual loot, most of which is of a rather underwhelming, neutral, or indifferent nature (as a matter of principle – and this is indeed all-important – there are no “real” artworks in Arden’s digital archive-gone-berserk). Pictures of “Altamont” – the Stones concert in 1969 that signalled the demise of the 1960s acid trip of love, peace, and happiness – are followed by “Aluminum” (photographs of household objects ); the “American Taliban” John Walker; “Apes, Planet of”; “Armour”; “Asphalt”; and so on – ad nauseam indeed. This humbling travesty of classification and taxonomy also relates back to art’s critique (“parody”) of the hegemonic epistemè of scientific thought, with its relentless insistence on making the world a transparent and wholly surveyable place – another tyrannical hallmark of the Hegelian master-slave discourse.

5. Quoted in Michel Foucault’s “Order of Things” (to which the title of the present essay, “Les Mots et les choses,” refers), Borges in turn quotes the imaginary example of a certain Chinese encyclopedia that grouped “animals” as follows: “a) animals which belong to the emperor, b) embalmed animals, c) tamed animals, d) milk sows, e) sirens, f) fabulous beasts, g) dogs without a master, h) those which belong into this grouping, i) those who behave like mad, k) animals painted with a very fine brush of camel hair, l) and so forth, m) animals which have broken the water jug, n) animals which look like flies from afar.” See Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of Human Sciences (New York: Vintage, 1994).

Roy Arden lives and works in Vancouver. He has exhibited his photographic and video work internationally since the late 1970s. In 2006, he will have solo exhibitions at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham; Monte Clark Gallery, Toronto and Vancouver; and Richard Telles Fine Art, Los Angeles.

Dieter Roelstraete was trained as a philosopher and currently works as chief curator at the Antwerp museum of contemporary art MuHKA, where he recently co-curated Intertidal, a survey show of contemporary art from Vancouver that included the work of Roy Arden. He acted as a co-curator of the Belgian pavilion at last year’s Venice Biennale (Honoré d’O, “The Quest”) and is a contributing editor to A Prior Magazine. He has written extensively on contemporary art and related philosophical issues. Based mainly in Brussels, Roelstraete now spends much of his time in Vancouver.

This text is reproduced with the author’s permission. © Dieter Roelstraete.