[Fall 2007]

online exhibition by Gallery TPW,

Toronto, ongoing

The emerging phenomenon of the virtual exhibition is creating both tremendous possibilities and challenges, particularly for photographers. Virtual venues offer new ways to disseminate and consider pictures, but current formats tend to privilege the curatorial imaginary.

Dubious Views houses two online exhibitions produced by Gallery TPW. Subversive Souvenirs presents artists’ alternatives to institutional representations of tourist sites. Subversive Cartographies does the same for mapping. The well-designed bilingual site features two essays that scroll along the left as the corresponding artworks appear on the right. The images can be clicked on for more information, and the essays’ hypertexts lead to definitions and art projects.

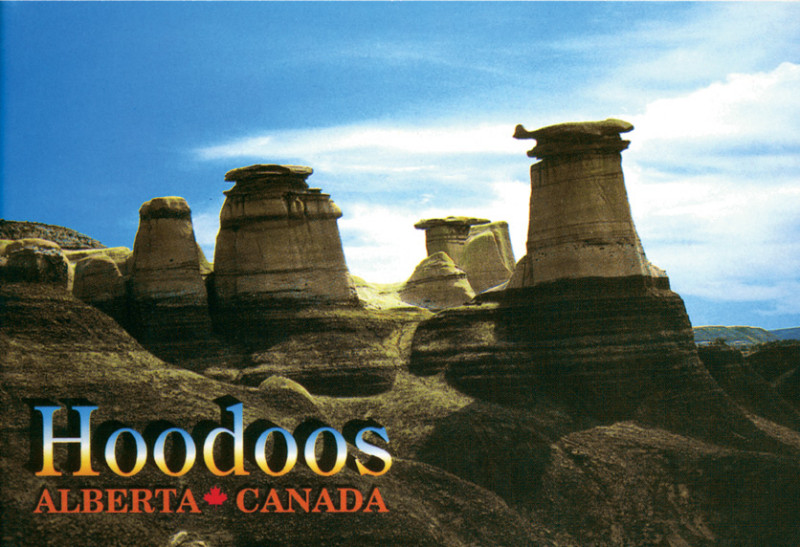

The artists are well chosen. Canadian favourites include Mitch Robertson, Janet Cardiff, and Shelly Niro. Jin Me Yoon’s self-portrait with a Lake Louise backdrop plays with the stereotype that Asiatic features in Banff are coded “tourist” and “foreign” and challenges us to examine our unconscious hierarchical ontologies of Canadian-ness. N.E. Thing Co.’s highway, marked with signs reading “start viewing” and “end viewing,” comments hilariously on the commodification of landscape.

Unfortunately, the essay is heavy on the theory of the spectacle and light on considering the works beyond this narrow filter. The unnamed author is more intent on convincing us that we are living in the Matrix than on unpacking the artworks. The viewer constructed in the curatorial essay is a dupe who believes tourist brochures and government propaganda and has no access to competing images and stories. This ripe fiction is a straw man designed to make the artists’ achievements uniformly and vaguely subversive (subversion as simply an alternative to the dominant). The author is not convinced that one version of reality is truer than any other – there are only competing versions. The text develops a strong thesis, then finds strains of it in the exhibition. This is firm essay construction, but perhaps curators should be more open to the greater complexities in the works that they tend.

If the essay simply accompanied the show it might not interfere with its reception. However, in the virtual format, it does intervene and is symptomatic of a general increase in the curatorial colonization of art. Curating is becoming more creative, more like art. In the conventional gallery, curators’ texts can be ignored; our experience with the art will usually overwhelm textual meanings anyway. However, current institutionally designed and funded virtual exhibitions tend to push the shift toward curatorial centrism.

If traditional spaces privileged things made by artists, virtual exhibitions privilege images and the curator’s words. Virtual exhibitions are a boon to virtual works. Artworks designed for the screen are no{t generally diminished by an online showing. But works with a primary, prior, non-Web identity are affected by the translation. There is an ontological difference between a tiny jpeg and Yoon’s large original. Too often, the miniaturization ends up becoming a quotation that serves the text meant to serve the artwork.

Current virtual gallery formats often have the curatorial voice share equal space with the art. In Subversive Souvenirs, the essay subtly overwhelms the art. At the top of the “exhibition” column are three images. The first juxtaposes the Eiffel Tower with firefighters responding to the recent Paris riots. The idea is that tourist images do not represent all of reality. The next picture shows people taking photographs of the pope’s funeral. The message is that people prefer to mediate their experience rather than get it directly. There is no line between the three essay illustrations and the art that follows. In fact, the Paris pictures might be a contribution to the exhibition by the author: they closely resemble Mitch Robertson’s work. This trespass renders the exhibition images into illustrations for the essay and the whole project more closely resembles a book format than an exhibition. Instructively, these problems are not as significant in Subversive Cartographies, in which much of the art is digital. In many cases, what we see (or search for, following the prompts) are the works themselves rather than small copies. Where the Souvenirs essay screens the art through Debordian theory and keeps only what it recognizes, the Cartographies essay is more porous and constantly overwhelmed by the art.

Ironically, the Subversive Souvenirs essay closely resembles the machinery that it critiques. The essay explains that dominant industry images – because they are visually appealing, government funded, authoritative and well distributed – displace competing versions. Dubious Views is a visually appealing, government-funded, and well-distributed set of images offering an authoritative version of certain artworks. Perhaps a text that deploys old-fashioned, oppositional, conspiratorial theory cannot afford to be blind to its own complicity in the image-making and contextualizing Matrix. Curators are more likely to produce new ideas if they follow the lead of the works rather than looking for theory matches that convert art into illustration.

David Garneau is an associate professor of visual arts at the University of Regina. His practice includes painting, drawing, curating, and critical writing. His solo exhibition Cowboys and Indians (and Métis?) toured Canada (2003–07).