— Marcel ProustDespite his pioneering role in the development of musique concrète, Hugh Le Caine (1914–77), a well-known physicist, inventor of electronic musical instruments, and self-taught composer, remains a relatively obscure figure: information about him is limited almost exclusively to his role in the evolution of electro-acoustic music and his scientific innovations.1

par Alexandre Robertson

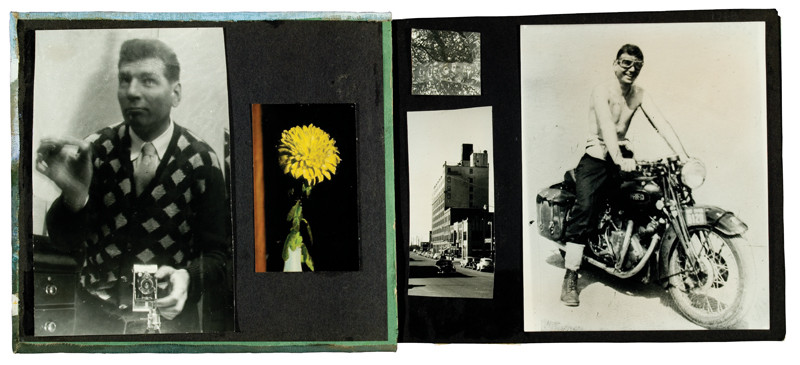

However, throughout his life, Le Caine compiled a private artistic production of collages, which he rarely shared with anyone: photographic albums, collages, and short films that, through the use of complex and original artistic processes, express the discontinuity between his public image and his personal life. These previously unpublished works were kept out of the public eye – in part because they were deemed too personal, but also because they raised certain questions about their creator’s sexual orientation.

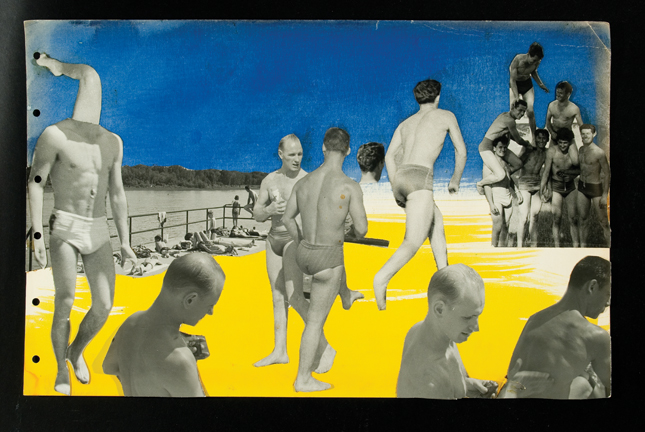

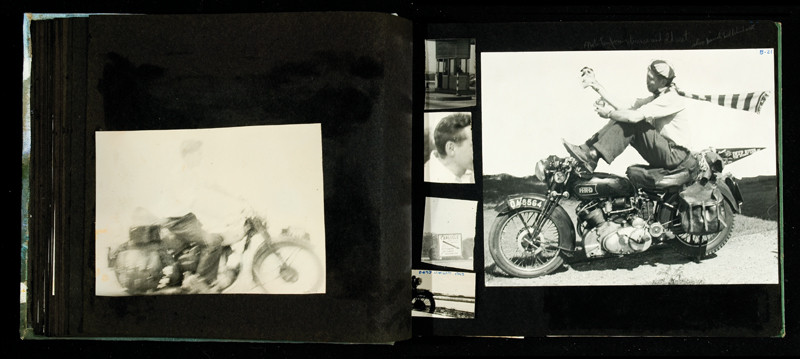

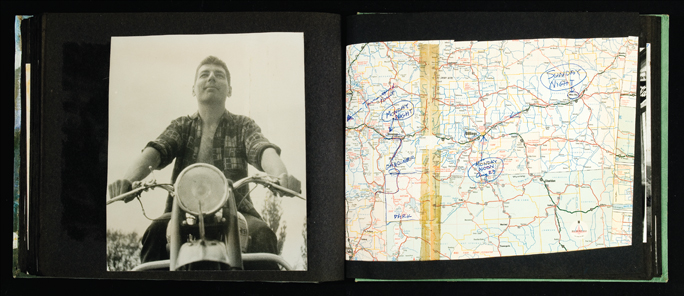

Maps, photographs, postcards, emotions, and attitudes: having mastered the art of recycling, Le Caine salvaged literary references,2 elements of popular culture, and images that were circulating in society at the time, then integrated them into the private world of his photographic albums. The photographs were annotated, marked with paint, or dipped in toner, and then cut out and arranged according to Le Caine’s whims on the albums’ black pages. Resisting any attempt at categorization, these works inhabit an ambiguous space between collage, montage, travel diary, and artist’s book. Begun between 1946 and 1949, when he repeatedly journeyed across North America by motorcycle – just as the Beat Generation was coming into being – they embody Le Caine’s quest for identity. Far from the documentary function of the travelogue or traditional photo album, these groupings of photographs are constructions that have more to do with fiction – or perhaps even self-fiction.

Through the Looking-Glass

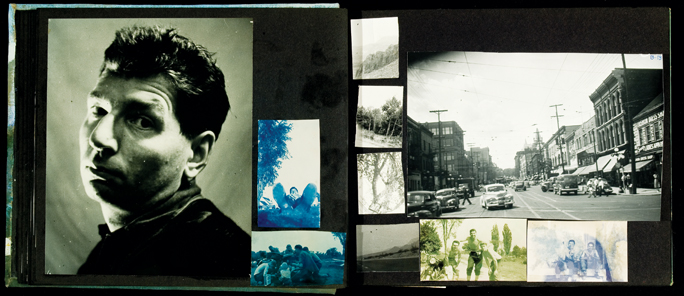

Self-portraits figure prominently in the pages of these subverted photo albums. Le Caine’s sketches of emotions and reprocessed memories are reflected in the warped mirror of remembering. The albums become a “cabinet of the self,”3 a space for introspection and self-examination. Is this a manifestation of his (multiple) public and private identities? The accumulation of self-portraits certainly seems to serve as a constant reminder of the dichotomy between his two identities, underlining by this very fact that it is well and truly Le Caine’s hidden face that is put forward here.

Le Caine is undoubtedly involved in the construction of an ecstatic personal geography.

This mise en abyme highlights the erosion of the distinction between portrait and self-portrait by maintaining the illusion of a relationship between subject and photographer. Nevertheless, we cannot help but feel a certain uneasiness when faced with this intense gaze – that stares at us without seeing us; that has eyes only for itself. Exclusively personal, the dialogue is that of a diary burst apart: a broken mirror that, like Le Caine’s collages, projects slivers of reflections in all directions and offers a fragmentary image of everything – or a mirror that, like Lewis Carroll’s or especially, Jean Cocteau’s (where it takes on a homoerotic significance), is the scene of a transcendence to an intimate and surreal world.4

It is a world in which Le Caine can direct, relive, or prolong encounters. Through the specific arrangement of images, the ambiguous relationship that is sketched among certain characters and the tendency to dwell on the photograph of such-and-such a young man (while concealing him and scattering him to the four corners of his album), Le Caine tries – consciously or not – to simultaneously express and conceal certain aspects of his life, as well as some of the feelings that he grapples with.

The albums contain numerous portraits of young men, which are often touched up with graffiti-like touches and sometimes delicately enhanced with colour or paint; these touches almost make one think of caresses. But sometimes the changes are applied with an intensity or feverishness that – although clearly not a mutilation or mark of violence – certainly symbolize affection or ownership, a taking of possession. Why does Le Caine alter these photographs? Perhaps through some conscious, critical strategy; or perhaps unconsciously, by interiorizing the social mores of the 1940s and 1950s.5

Of course, as is the case for many artists of that time, the clues to Le Caine’s sexual orientation, even in these private albums, are relatively subtle. Yet, although he did not participate in contemporary homosexual life, these works demonstrate a familiarity with the iconographic and typological repertoire of gay roles and representations of the twentieth century, and sometimes seem to refer to a homosexual experience that is just beyond the frame of the image.6 The self-censorship that Le Caine performs is a natural reaction to the social context of a period hostile to any display of homosexual desire.

Scientific, Artistic, and Identitary Paths

Beyond the exploration of his impulses and identities through collage, other ferments of inspiration also fed into Hugh Le Caine’s research. Art allowed him to express elements of the theory of relativity, which had revolutionized physics in the early decades of the twentieth century. At the time, few artists had actually integrated this scientific upheaval into their production; Le Caine’s mixing of physics and collage as early as the 1940s would seem to have made him a precursor of this new approach. In fact, the artistic strategies that he used to handle the notion of identity are a direct result of his familiarity with what were then the most revolutionary aspects of nuclear physics. Le Caine applied space-time permutations to his albums, slowing, accelerating, telescoping or compressing his memories, and infusing static images, through the juxtaposition of powerful iconographic signs, with an energetic, identitary, or sensual potentiality – constructions informed by the encounter with the “new” quantum space-time. He chose to execute them using collage, which seemed to lend itself particularly well to the expression of changing concepts of time, space, and reality that emerged throughout the twentieth century: by cutting up images and information as if they were molecules to be split and reoriented, synthesizing worlds in which relativist compressions and dilations take place,7 and manipulating particles of light and sound with a thorough understanding of their properties.

The Persistence of Trajectories and Signs of Passage

The links between relativity and travel are inevitable. After all, is it not reasonable to believe that the mechanized motion of the locomotive (and its never-before-attained speeds) could have had such an effect on the manner of seeing the landscape that it may have set the stage for the emergence of the theory of relativity? As Peter Osborne writes, “Where there is no centre there can be no central medium; where there is no stasis there can be no static point of view. Everything is transformed by the condition of travelling.”8 Le Caine’s irresistible desire to travel by motorcycle is significant, since both his artistic and identitary experience and his comprehension of space-time are fundamentally changed by it. The maps that he placed in the pages of his albums, tracing the routes of these voyages, are true experiential collages: they serve as a reminder of the encounters and events that transpired during his travels. Although they do not necessarily express the long association between travel and sexual adventure,9 one can nevertheless discern inscriptions situating certain events and encounters (for example, the note “Friday night – Motorcyclists”) that occasionally touch on a certain ambiguity. 10 In fact, the accumulation of images seems to be concentrated around these “singularities.” In his own way, Le Caine is undoubtedly involved in the construction of an ecstatic personal geography.11

Are the experiences displayed entirely true, false, or exaggerated? It is impossible to say. We must rely on Le Caine’s words and memories, which inhabit the hazy borderland between fiction and reality. But perhaps this is beyond the point. After all, according to Le Caine’s own relativist perspective, reality is dependent on the observer’s point of view: his take on events is therefore as valid as ours. And this point of view is fundamentally rooted in the notion of travel, itself central to the contemporary conception of identitary processes.

Le Caine is the ideal postmodern subject: he resists the pressure to forge and maintain a fixed identity, and instead seeks to live and relive experiences while maximizing the array of possibilities available to the Self. These multiple identities are based on an accumulation of sketches of existences: the individual, fragile, incomplete parts are structured by repetition; identity is solidified by their union. The collage is never finished. Le Caine thought of himself as a work in progress, eternally evolving, who, in order to realize his fullness, must – at all costs – remain uncompleted.

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 The major exception is Sackbut Blues, a fascinating biography of Le Caine published by musician Gayle Young. She was not, however, granted access to certain private documents.

2 Notably James Joyce and Marcel Proust. It thus seems appropriate that the notes Le Caine gathered with a view to one day writing his autobiography bore the name Recherches au temps perdu, a play on words on both his scientific work and his occasional excesses of modesty.

3 Martha Langford, Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001), p. 41.

4 It is, incidentally, interesting to note the symbolic power of the mirror in expressions of homosexual culture at the time.

5 A collage by Robert Mapplethorpe (Bull’s Eye, 1970) highlights this strange relationship with images, informed by censorship. See also Richard Meyer’s Outlaw Representation, which recalls the once-common practice of censoring homoerotic images by withdrawing or masking the part judged “obscene” – and the potential that this practice had of thus “eroticizing” the fragmentation.

6 Jonathan Weinberg, Speaking for Vice: Homosexuality in the Art of Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and the First American Avant-Garde (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), p. 62.

7 See, for example, his famous composition Dripsody [Rhapsodie d’une goutte d’eau](1955).

8 Peter D. Osborne, Travelling Light: Photography, Travel and Visual Culture (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), p. 184.

9 Ibid., p. 16.

10 One should note the importance of the motorcycle – a symbol of freedom and virility – in the homosexual iconography of the time. But for Le Caine, it is also an experimental mechanism whose driving force allows him to experiment with changes in speed and new points of view on reality, and whose symbolic force enabled him to free this corporal potentiality and sensual energy.

11 Osborne, Travelling Light, p. 129.

Alexandre Robertson is an artist and art historian who lives in Montreal. This essay is a brief summary of his master’s thesis, Collage éthique et esthétique: arts, sciences et quêtes d’identités dans les albums photographiques privés de Hugh Le Caine (Université de Montréal, 2006).