[Winter 2012]

by Mona Hakim

The name Serge Emmanuel Jongué (who died in 2006) was not unknown in the photographic community. In his important essay titled “The New Photographic Order,” published in 1990,1 Jongué cast a lucid eye on the issues in Quebec documentary photography in the 1970s. His reinterpretation of the official discourse attached to this photographic school has become a classic for those interested in the history and comprehension of Quebec photographic practices. What is less well known, however, is that an experienced photographer existed behind the writer’s pen. Although his works were well known in Europe and had good exposure in Quebec – usually, it must be said, in “non-institutional” venues – they are not well enough known here. “Boarding Pass,” the exceptional exhibition devoted to Jongué’s work on all three floors of the Maison de la culture Côte-des-Neiges from 8 September to 15 October 2011, brought to light a powerful and deeply disturbing body of photographic work. Organized by curator Serge Allaire, this generous, substantial retrospective (almost 250 images) redresses the lack of recognition of an artist who has up to now been deprived of a critical reception worthy of the name, but who nevertheless occupied a unique position in Quebec and Canadian photographic practices in the 1990s.

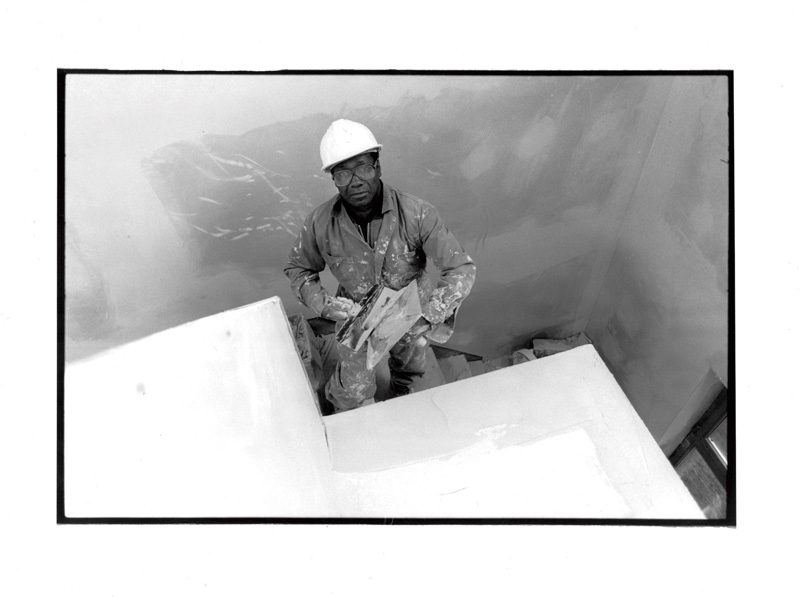

Born in France to a Guyanese father and a Polish mother, Jongué immigrated to Montreal in 1975. With a degree in literature from the Université d’Aix-en-Provence, where he studied comics, he undertook doctoral studies at the Department of French Studies at the Université de Montréal. The visceral connection that he maintained with text and image followed him throughout his professional career as a critic, historian, poet, and photographer. In the early 1980s, Jongué began a career as a journalist and art critic, notably for the magazine Vie des arts, for which he wrote a regular column. At the same time, he began to practise documentary photography, taking pictures at Montreal’s union centrals, for which he covered demonstrations and events in the life of workers. He was also involved with community groups, particularly the immigrants in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood in which he lived. The first of the two sections of the exhibition opens with the series Identités métropolitaines (1990–91), composed works within the photojournalistic tradition that confirmed for Jongué the power of images to construct the memory of a working-class immigrant culture. Having taken the measure of some ten thousand kilometres in the metropolitan region, and having taken the seven thousand photographs upon which the corpus is based, Jongué felt free to express his own way of seeing and feeling Montreal – of “rediscovering the odour of an undreamed-of city, funny, charming, hybrid, black, white, café au lait,” as he wrote in his personal notes (our translation). “Feeling,” he continued, “with an unbridled, uncluttered attitude toward both fashions and classical canons.” The works in this series, like those in Portraits dénudés (1998–99),2 were decisive in his career; they ended one cycle and heralded the beginning of a new approach, as he gradually began to investigate the aims of the photographic act and its secular function as a social document. From this point on, driven by nomadism, his inner voyage, and a quest for identity, Jongué would make room for more personal writing while provoking a critical reflection of traditional ideas about identity and personal memory.

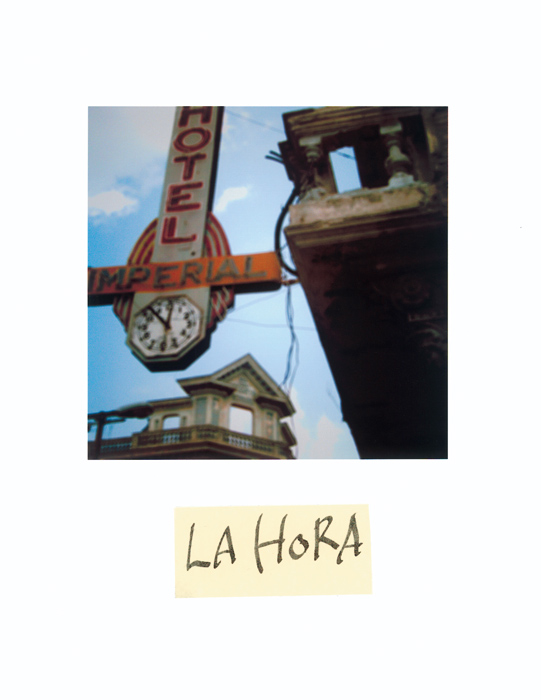

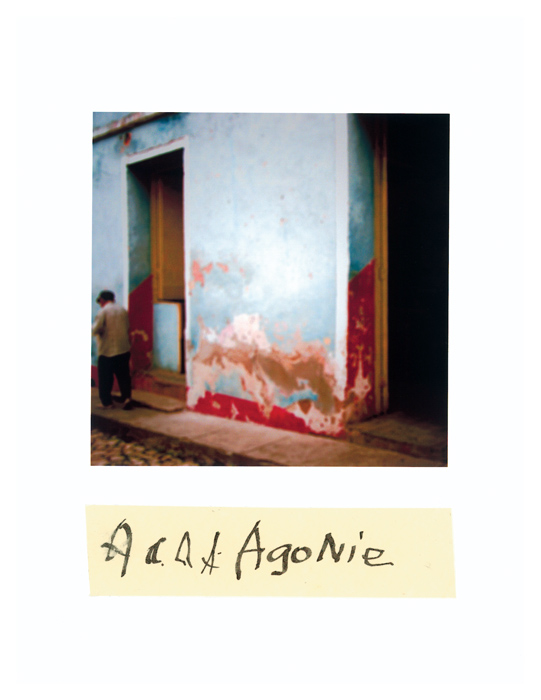

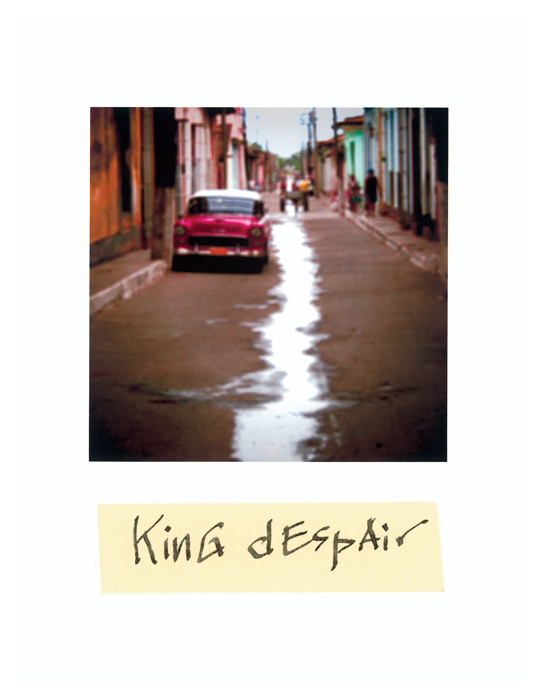

In evoking the idea of imaginary voyage and mixed blood, projects such as Nomade (1990–91), Métis (1997), and Boarding Pass (2000) bear witness to the impact that his urban travels had on how he constructed their mental dimension. By turning the camera lens back on himself, Jongué immerses the viewer in an intimate, poignant world. Forming the second section of the exhibition, two floors of the Maison de la culture are devoted to this more introspective period, the largest of the rooms holding most of the works, and perhaps the most moving ones. Jongué’s voluminous and dense body of work is populated with alleys, architectural references, hybrid objects, furtive figures, and close-ups of enigmatic faces – captured on the fringes of his many wanderings – that seem to have been hunted down as he was gripped by a sense of urgency. Against this expressionist iconography is juxtaposed feverish writing, sometimes taking precedence over the images, at other times in the form of a title written under the image, but always indissociable from it. Both texts and images manifestly convey the artist’s frenetic desire to trace back his origins through an act that is both imaginary and autobiographical. For Jongué, words are attached to images in a way that is shifted, as if they are reconstructing gaps in an individual and collective history.

“What I cannot photograph,” he stated, “I can write.” It is important to note that Jongué took most of his images with a Polaroid. The use of this type of camera seems to respond to an innate need to react spontaneously to events, to capture and fix emotion in the moment. Although some series of images were transferred from Polaroid to digital, they were reframed in the square format of the original camera – a systematic, non-negotiable aspect of how it produces pictures. The recurrent choice of the small format and the accumulation of images produced by this method offer a good demonstration of Jongué’s compulsive attitude toward capturing the events of his daily life on the fly, and of repetitively and insistently telescoping the multiple episodes of his mental path. And then, there is the omnipresent blur, which deepens the mystery of the images and literally haunts the viewer. It is an almost ghostly rendering, which not only conveys the ephemeral nature of perception but confirms the vulnerability of the photographer behind the subjects, as well as his reminiscences and his often tragically inflected states of mind. Thus, moving into this post-documentary body of work entailed, as he specified in his notes, “a preoccupation with the visual in which the photograph is envisaged as raw material rather than referent to representation.” The out-of-focus images, subtitles transcribed onto adhesive tape (the pentimento was left visible in the digitization process), and constancy of the geometric format of the pictures are all incursions into the photographic material that testify to Longué’s unremitting quest to materialize the traces of the mental space and his obsession with capturing the unspeakable. It has been said that Jongué was a creature of impulse. Notebooks, books, pictures, objects, and souvenirs of all sorts accumulated through his mental and emotional travels. To prepare the exhibition, curator Serge Allaire had to bring order to the artist’s archives by sorting, numbering, and analyzing them. In addition, he had to read all of the notebooks in order to become immersed in Jongué’s abundant, impassioned world. This enormous task took more than a year and a half of sustained research. Marie-Josée Lacour, the instigator of the retrospective that pays tribute to her longstanding companion, was an extremely valuable contributor, attentive to each step of the project and allowing access to the voluminous photographic and handwritten production as well as to the atypical collector’s artefacts.

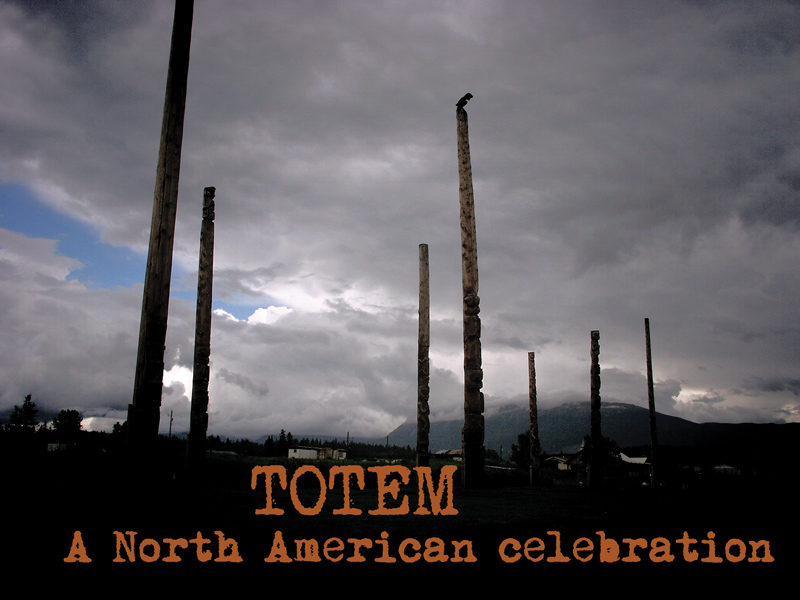

In an effort to respect the integrity of the body of work by sticking as close as possible to Jongué’s approach, Allaire produced a significant exhibition relating the evolution of the artist’s production in terms of both major conceptual themes and emotional charge. Grouped into series, the images are lined up in sequential order, in the spirit of the narrative line and the haiku form so dear to the artist; each series can be considered to be a project, like a sort of text in itself. What is more, the hanging arrangement, which isolates each project, allows visitors to take a break as they stroll and gives the exhibition as a whole room to breathe, thus warding off the chaotic effect that the profusion of images might have produced. Of course, the photographs’ small format easily lends itself to the serial system, so that we enter these mosaics of images as if entering a register of living emotions, leading us to an attentive, proxemic, slow, almost contemplative reading of each part of the photographic story. Similarly, two showcases containing artefacts that belonged to the artist – such as notebooks, typewriter, camera, contact sheets with scribbling on them, and books on the black liberation movement and on photographers such as Robert Frank (his mentor) – give an enlightening and touching overview of his mental and creative universe. On the main floor, the compelling titles attached to the surface of images, such as Desire, The Dead Man, Darkness, Le chagrin, and Street Fire, clearly spell out the state of mind of a tormented man who is more and more haunted by death. The Passenger series (2002–04), made almost two years before his death, is disturbing in this sense for its sense of premonition. Âme déposée, Le deuil, La mort 5 : am, and Tombe bleue are among the ten photographs in this series, hung on a partition in the centre of the space that acts as a stele, a monument pivoting at the heart of the projects Undressed Passion (2000–03), Boarding Pass (1999–2000), Objets de mémoire # 2 (1994–2005), Totem (2004–05), and Suite cubaine (2002–05).

This more memorial aspect of the exhibition is echoed in the totemic structure, perceptible at several levels, of the series Totem, Objets de mémoire # 2, Indian’s Land, and Métis-Installation. It reveals, above all, Jongué’s fascination with Aboriginal culture and his explicit desire to become integrated into Americanness. After all, the totem is a widely recognized to be a symbol of family ties or adoption by the community. “Formally,” notes Allaire in the press release, “the totemic structure used here makes it possible to bring together the few fragments of an identity and, in the same breath, symbolically states its inscription in Canadian culture and, more broadly, in Americanness, as is manifest in the title of the project, Totem, A North American Celebration.” In fact, the close-ups of totems and of majestic trees sculpted by time (these shot north of Graham Island) both question the notion of temporality and shore up the metaphor of the crossing from a state of nature to a state of culture.The totemic figure is also evoked in the cruciform arrangement of each of the four projects in the installation Métis (1990–96)3 – the four projects, it should be noted, had already been part of the artist’s first major exhibition at the art gallery at Bishop’s University in 1999.4 For the retrospective, curator Allaire has respected in its entirety the installation plan found in Jongué’s notebooks. We enter the small gallery on the first floor, in which there is only the one piece, as if entering a chapel, with its subdued lighting and muted jazz music (of which Jongué was fond).

To put things in context, it should be noted that starting in the 1990s, when Quebec nationalism was entering a vigorous phase, Jongué’s work was part of a movement of critical reflection rethinking the foundations of an ethnic-based nationalist identity usually defined as monolithic. A number of eminent writers, including Sherry Simon, Régine Robin, Pierre L’Hérault, and Alexis Nouss, were putting into sharp focus the question of Québécois identity (through its literature), from the angle of identity and heterogeneity. Québécois literature “can be thought of no longer as completed, but as opening,” stated Pierre L’Hérault, “and diversity perceived no longer as a threat but as the sign of the inevitably multiple reality.”5 In Jongué’s view, the idea of a monolithic identity was opposed to the hybrid nature of his personal experience, shaped by mixed origins and diversified migratory trajectories. And it was in this same context that we can understand his critical discourse of the 1990s with regard to Quebec documentary photography, which, he wrote, “prefers to maintain the comforting illusion of social cohesion: it wants above all to be liked, to the precise extent that it feeds the permanent desire to describe a homogeneous group rather than confront the growing disparity of a society in rapid transformation.”6

From the aesthetic point of view, the transition from documentary to an introspective approach positions Jongué’s photographic production within the subjective, more “mixed media” practices that arose in the 1980s and 1990s in Quebec. “By favouring the fragment, the hybrid, and the heterogeneous in identitary construction, [this production] contributes significantly to defining, between autobiography and self-fiction, the terms of self-representation,” observes Allaire, “and because of this it participates in the elaboration of post-modernist issues in Quebec photography.” I would add that beyond the sometimes impenetrable and introverted nature of the iconography, we nevertheless detect in this humanist, engaged artist a desire for access to the Other, as an almost visceral need to include excerpts of a collective memory in the definition of a cartography of the private. In this sense, Jongué’s work stands out from recognized autobiographical modalities and is thus unique among Quebec practices.

We must thus acknowledge the curator’s exemplary research and exhibition design, as well as the determination of Marie-Josée Lacour to pursue her efforts to have her companion’s work recognized. A foundation in the name of Serge Emmanuel Jongué has since been created to encourage research, distribution, and legitimization of his body of work. A very sensitively written book by Lacour was also launched at the exhibition. Les contours de l’imaginaire seeks to revive, through the artist’s artefacts, photographs, and writings, the mental and emotional traces that imbued their life together.7 Furthermore, a different selection of projects, including Mémoire aux yeux clos, was exhibited at Galerie Simon Blais at the same time as the retrospective in order to introduce this unique body of work to future collectors.

Although the black community has had much to do with the recognition of Serge Emmanuel Jongué, the retrospective Boarding Pass, which has brought this artist out of his relative anonymity, has shown us that there are still efforts to make to fill certain major gaps in the history of Quebec photography.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 This body of work was produced at the Carrefour Jeunesse-Emploi de Côte-des-Neiges, an agency frequented by young people from various parts of the world, who gave Jongué a few minutes to take pictures of them.

3 Three of the four projects in the Métis installation were part of a larger project titled Contredanse, a polyphonic photographic novel that was never completed.

4 In this regard, I must mention the insight of Gaëtane Verna, at the time director of the art gallery at Bishop’s University in Lennoxville, who believed wholeheartedly in Jongué’s talent. When she was director of the Musée d’art de Joliette, she also presented Totem, La Messe américaine, in 2007, one year after Jongué’s death.

5 Pierre L’Hérault, “Pour une cartographie de l’hétérogène : dérives identitaires des années 1980,” in Sherry Simon et al., Fictions de l’identitaire au Québec (Montreal : xyz éditeur, 1991), p. 56 (our translation).

6 Jongué, “New Photographic Order,” p. 47 (our translation).

7 Serge Emmanuel Jongué and Marie-Josée Lacour, Les coutures de l’imaginaire (Montreal, éd. du cidihca et Fondation Serge Emmanuel Jongué, 2011).

Born in France to a Guyanese father and a Polish mother, Jongué immigrated to Montreal in 1975. With a degree in literature from the Université d’Aix-en-Provence, where he studied comics, he undertook doctoral studies at the Department of French Studies at the Université de Montréal. The visceral connection that he maintained with text and image followed him throughout his professional career as a critic, historian, poet, and photographer.

Mona Hakim is an exhibition curator and an art historian and critic. She has written numerous books, monographs, and catalogue essays. Her field of interest is contemporary photography. As a curator, she has organized fifteen solo and group shows, in Canada and abroad. She teaches art history and the history of photography at CÉGEP André-Laurendeau in Montreal.