[Fall 2006]

by James D. Campbell

I am inhabited by a cry. Nightly it flaps out

Looking, with its hooks, for something to love. – Sylvia Plath, “Elm”1

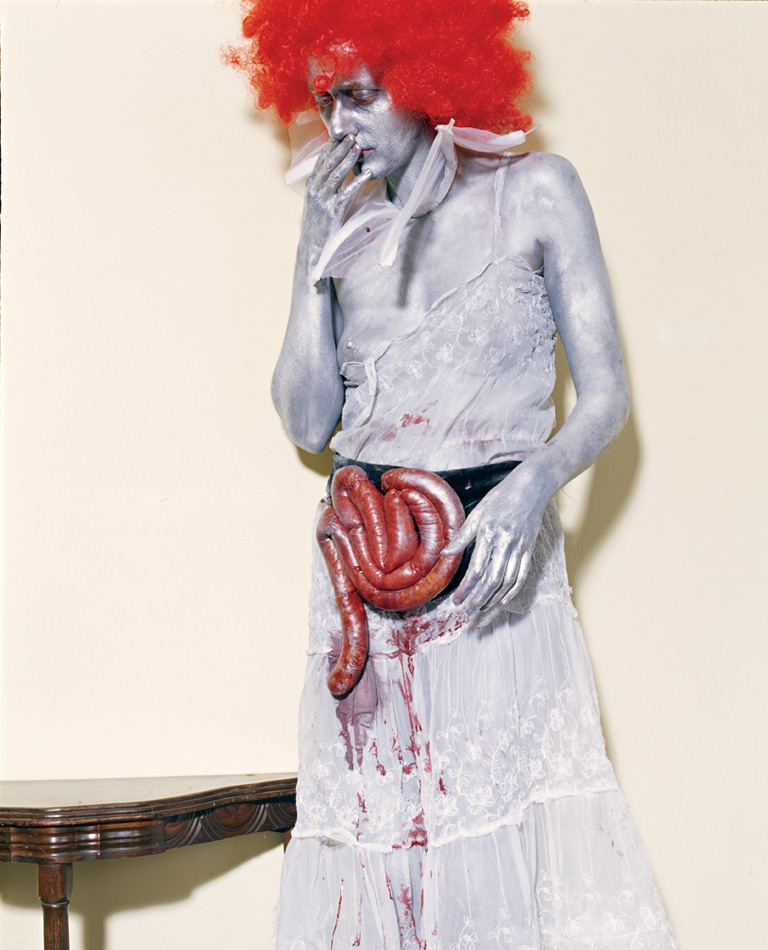

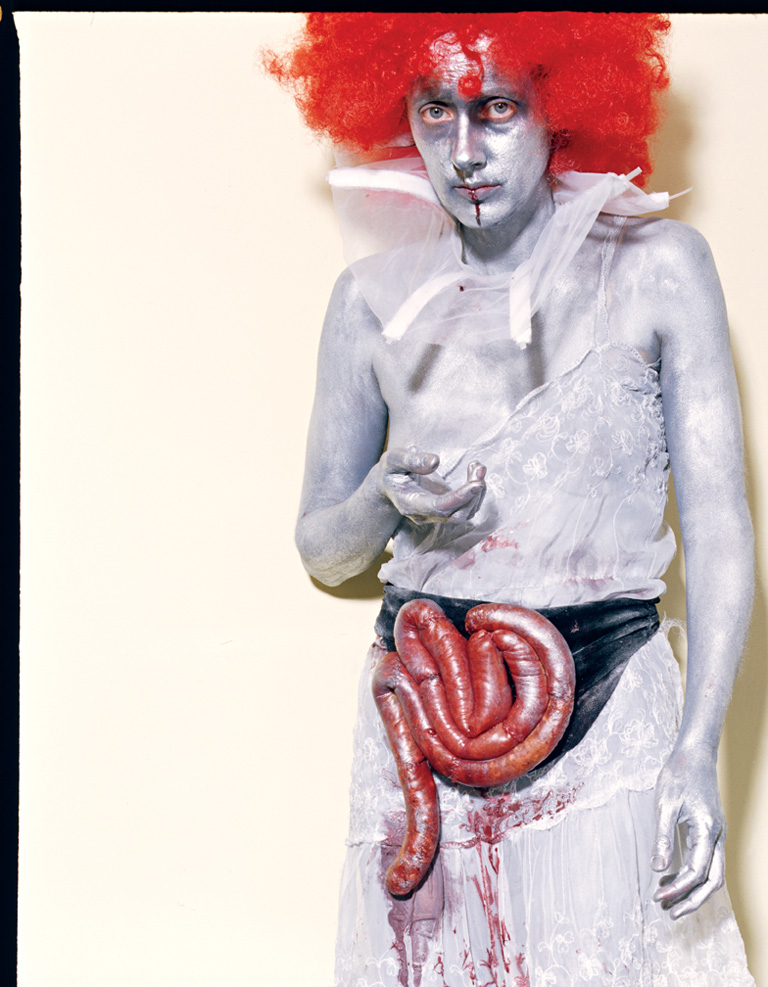

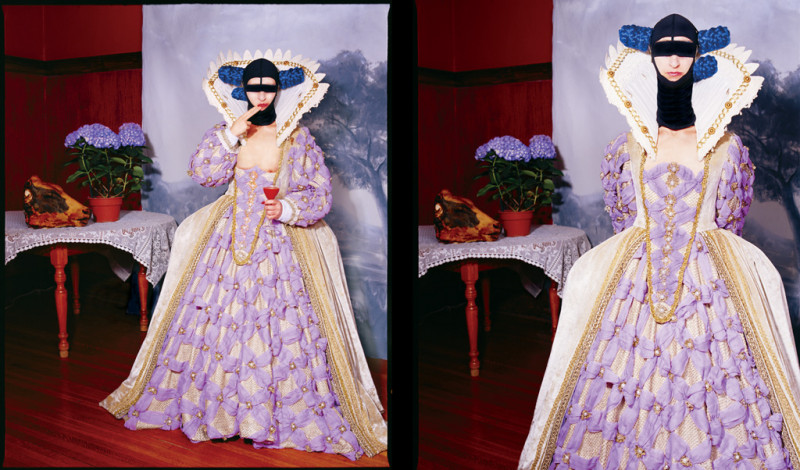

No other contemporary photographer’s work has come closer to being inhabited by Plath’s cry, quoted above, than that of British-born, Toronto-based artist Janieta Eyre. Indeed, that fatal cry is incarnated harrowingly well in her recent thematic series of theatrically staged photographs – so well, in fact, that it is simply impossible for us to remain deaf to its compellingly funereal overtures, for it flies into her viewers’ life-worlds with feral intensity. Eyre has evolved her own signature manner of “melancholy grotesque.” Her imagery and the territory that she stakes claim to are wholly and uniquely her own. And, for all its theatricality, her work refuses easy answers, and it can and does eviscerate hypocrisy and convention.

Eyre pursues the myriad raptures and ruptures of being across her own inner thoughtscape courageously and with abandon. Never one to shy away from images that might be construed as gratuitously lurid or even outright loony, she revels in unfurling their most painful implications like patterns on yellow wallpaper2 – and she seems just unstoppable.

And she stops us in our tracks at every juncture with the stark, hallucinatory clarity of her visual language. Never completely benign, even when ironic whimsy holds sway, never wholly annihilating, even when darkness moves restlessly across it, her imagery can be at once unsettling, hypnotic – and eminently twisted. It is always epic in scope.

Viewing Eyre’s photographs reminds me of the vicarious pleasures to be had in ogling the instrumental eye candy of capital operating and amputation sets from the Civil War era, whose aesthetics were ineluctably wed to their implementarity. One may be seduced by the sight of Tiemann crosshatched ebony saw handles aglow with soft polish, and Liston knives looking unbearably sharp, and trepanning instruments ready to burst forth from their velvet beds in rosewood cases to relieve the pressure inside swollen, wounded heads. Across a wide array of imaginary tableaux – and with razor-sharp precision and a prophylactic grain of ironic whimsy – Eyre transfixes our voluptuous optic and performs her own trepanning op. There is something deft and vivisector-like about the hands that work the surgical steel under cover of darkness or, for that matter, in plain sight. There is a real frisson to be had in experiencing her work.

For a long time now, Eyre has been working up a private mythology that integrates her own promiscuously imaginative and wayward imagery with the effluvia of a very deviant thought-world. In series such as Lady Lazarus, Motherhood, Rehearsals, and Incarnations, her dreamscapes morphed into what seem to be waking nightmares, altogether unnatural in mien for the viewer but probably, for her, very natural and pertinent.

In her recent series What I haven’t told you (2003–06), her melancholy has never been more unfettered, auratic, rapturous. In this respect, the work demonstrates a hard-won emotional integrity. It reminds us of Sylvia Plath’s poetry (and her journals), David Lynch’s dark cinematographic fables (particularly the early shorts but Lost Highway, too, with Robert Blake in Luciferian whiteface), and Diane Arbus’s similarly unflinching, hungry, and interrogatory eye. In fact, Eyre seems to be the natural heir to Arbus for the twenty-first century.

Of course, Eyre’s photographic work is, above all, a methodical amplification of her own interior life. Her works are no-holds-barred meditations on madness and melancholy by an artist in close touch with her own unconscious – and one with a demonstrably cinematic gift.

Her mythology has a demonic aspect, too – one that transcends mere nightmare yet is always on the cusp of expression. Ghosts are birthed and channelled there. In the past, she has been obsessed with spectral apparitions and has looked closely at nineteenth-century spirit photography that suggests both etheric plasma and the afterlife, and the psychic energies that she channels are aggressively fey and wilful.

Rudolf Otto names the feeling of numinous dread with the Latin phrase mysterium tremendum. 3 This succinctly expresses our feelings in front of Eyre’s work. Perhaps her spectres attract us because they are wholly Other and induce in us an astonishment which is, after all, a very human response to the numinous. It may repel at first, but it then stakes an irresistible claim upon us. Dread and helpless fascination are co-extensive in our experience of Eyre’s work and exert in tandem an inexorable pull.

In The Metamorphosis, Kafka’s lovely entomological nightmare, Gregor Samsa emerges from a human chrysalis like a chitin-wrapped gift from the insect world. Kafka’s is a fable of the tremendum – and a bracing meditation on melancholy, mutilation, and mutation – for Samsa’s body has become its own nameless Other. Kafka was perennially attempting to communicate the incommunicable, and perhaps Samsa’s struggle mirrored his own. So too, Eyre, in brave acts of doubling in her staged photographs, gives voice to the inexplicable and inexpressible as she makes the perilous transit from the one to the many in work as intractable as it is intense. If words for Kafka were his only way out, images for Eyre are her only way in.

Eyre has been compared to New-York-based artist Cindy Sherman, but I think she shares more with Joel-Peter Witkin. Francesca Woodman is another obvious comparison, but I find a more eloquent predecessor still in Ralph Eugene Meatyard, whose photographs still count among the spookiest around. Like Meatyard, Eyre is utterly unafraid in her work; she always moves beyond anything like conventional imagery and meanings and embraces the far side of her project, which most often integrates her own image doubled, opening up consummately strange parallel universes in which to waylay the unwary viewer in a vivisectionist’s hook-fraught wonderland.

In the astonishing polyptych What I haven’t told you (2003), Eyre appears in multiple like clones that are melancholy but also look, frankly, pissed. Their Eros may be melancholy, but the prospect of vivisection invests the melancholic with a decidedly sadistic twist. In I had to have a small operation (2004), Eyre replicates herself into four unhappy transgendered selves. Still, she is best known for her doppelgangers, and the promise of their death-bound subjectivity is pervasive. Eyre’s art is one of totalizing interiority.

In commenting on Eyre’s work, I am drawn to the work of a fellow traveller: St. Petersburg-based director Aleksei Balabanov. His Of Freaks and Men is a lush and vivacious wedding of porno, insanity, the sex life of Siamese twins, and the whole wounded madhouse of our time brought up close and personal. Eyre’s own Siamese twins fantasia, Dress with Hole in the Heart, comes immediately to mind. Her ironic, whimsical perversity certainly matches Balabanov’s. His is a real freak show, of course, but it is a truism of our condition that we are all freaks to a greater or lesser extent. This uncomfortable truth comes home to us in regarding Eyre’s work. Of Freaks and Men, like What Haven’t I told you, may seem nihilistic but, upon closer inspection, this is far from the truth. And it is alterity that is the touchstone.

Eyre’s Ophelia-like self-portraits, skin whiter-than-white, have a distinctly Gothic feel without the overt trappings of contemporary Goth. Her penchant for funky cosmetics, crinolines, knee-high stockings, masks, bandages, vibrant patterning, blindfolds, and so forth is radiant and helps to amplify her “melancholy grotesque.” There is no dead space in Eyre’s images. Everything resonates. And the humour in her art is most often pitch-black. If you miss it, you miss out on the lighter touches, albeit limned with portents of exclamatory darkness as they are.

Eyre has said, “I have in my mind this elusive place, a home in which every room is painted in a different colour and at each doorway is a different costume. This is where I hope to end my life.”4 The quotation is interesting, because it reminds us how close she is in spirit to Jean Ray’s masterpiece of the Romantic grotesque, Malpertuis. The strange intensity of that tale, in which events surge up with wild clarity as in a fever dream, induces in the reader a consummate sense of dread, much like that brought on by Eyre’s recent works. Malpertuis (House of Evil), the many-roomed mansion of the title, echoes those rooms in which Eyre hopes to end her life. Her doppelganger is reminiscent of Lampernisse, the mad hermit who haunts the mansion’s labyrinthine halls. The splendid melancholy of that modernist Gothic novel slowly seeps out like adhesive sap that gilds all the rooms in its namesake. Giddy in self-consciousness but never merely narcissistic, and rich in dark fantasy, Eyre’s photo works thematize their own melancholic content from series to series, work to work.

Let us return to Kafka for a moment. Samsa’s predicament is much like that of any person suffering from melancholy in its malignant form, like Plath’s cry, which can disfigure the spirit as tumour and metastasis do the body. Kafka draws on his own melancholy, adding lustre and authenticity to all the dark adjectives that are in mind to say. A new chitin jacket means perceiving differently from before; senses are sharpened, spatial perception changes, and so forth. Similarly, Eyre is aware that today identity is entirely mutable. Her own metamorphoses verge on the sublime, in that it is difficult to tell where in her work the numinous leaves off and the sublime begins, and vice versa. The sublime, like the numinous, defeats all attempts at taxonomy, preserves its own mysteries and is thus the strangest and most compelling of attractors.

Eyre’s fidelity to her own private spectres, to numinosity and the sublime, and our ongoing infatuation with all of her possible worlds, makes us hopeful for the many metamorphoses that are surely still to come.

2 The reference is to Charlotte Perkins Gilman, The Yellow Wallpaper (first published 1899 by Small & Maynard); Gilman is a kindred spirit of Eyre’s.

3 See Rudolf Otto, The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry into the Non-rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and its Relation to the Rational (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958).

4 See Russel Joslin, “Interview with Janieta Eyre,” in Shots, No. 84 (May, 2004.)

Janieta Eyre lives in Toronto. Since 1995, she has had a number of personal exhibitions and her work has been shown regularly in Canada, the United States, and Europe (particularly Italy). She is represented by Christopher Cutts Gallery, in Toronto, Diane Farris Gallery, in Vancouver, and B&D Studio Contemporanea, in Milan.

James D. Campbell is a writer on art and independent curator based in Montreal. The author of over a hundred books and catalogues on art and artists, Campbell contributes frequently to art periodicals such as CV ciel variable, Border Crossings, Parachute, Canadian Art, and ETC. He has taught history of photography at the University of Ottawa.