Jean-François LeBlanc

Les Montréalais: portrait d’une fin de siècle

Maison de la culture de Côte-des-Neiges

from April 6 to May 21, 2017

by Tema Stauffer

A retrospective of ninety-five black-and-white photographs by Jean-François LeBlanc was recently exhibited at Maison de la culture Côtes-des-Neiges, presenting a look back at a fertile decade of life in Montreal beginning in the mid-1980s. A native of Montreal, Leblanc began his career on assignment for community organizations and weekly newspapers gathering images of the streets, parks, public pools, clubs, festivals, rodeos, rallies and religious rituals that defined the social and cultural fabric of the city and its passionate celebrations, clashes, and contradictions. The largest exhibition of Leblanc’s work to date, Les Montréalais: Portrait d’une fin de siècle conveys a perspective that is insightful, humorous, and, at times, provocative.

“Many of these images would be very difficult to do today,” said Leblanc about the work in the exhibition. For example, his iconic image of an eighty-five-year-old man diving into a crowded swimming pool in Laurier Park would be impossible to shoot now, according to Leblanc, who stood behind his subject on the diving board to compose the shot in 1986. “You can’t enter a pool with a camera,” he lamented. “People are harder to photograph in public and access to environments for photographers is more restricted.”

One of his most controversial photographs catches a Santa Claus figure, from the back, at a urinal in the men’s bathroom of a Desjardins banking centre in downtown Montreal. Leblanc followed his subject into the bathroom to furtively make this photograph, and he was later nearly sued by the bank. The photograph becomes all the more provocative displayed within a series of images documenting religious events, such as a bride at a church wedding and Catholic nuns at a funeral, juxtaposed with another group of shots revealing glimpses into Montreal’s nightclubs and leather scene.

Although Leblanc took a handful of photography courses while working on an undergraduate degree in communications at the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQÀM) in the early 1980s, his experiences working on assignment are largely what taught him about taking pictures. Shortly after graduating from UQÀM in 1983, he was commissioned by a healthcare centre in St. Henri to document residents of the neighbourhood most of whom were employed by factories and warehouses, and his portraits of this racially diverse working-class community are among the most powerful photographs in the exhibition. In an especially penetrating image, a young boy peers directly at Leblanc from a parked car on the street, while a girl in the driver’s seat looks away from the photographer, her faraway gaze perhaps focused on an uncertain future.

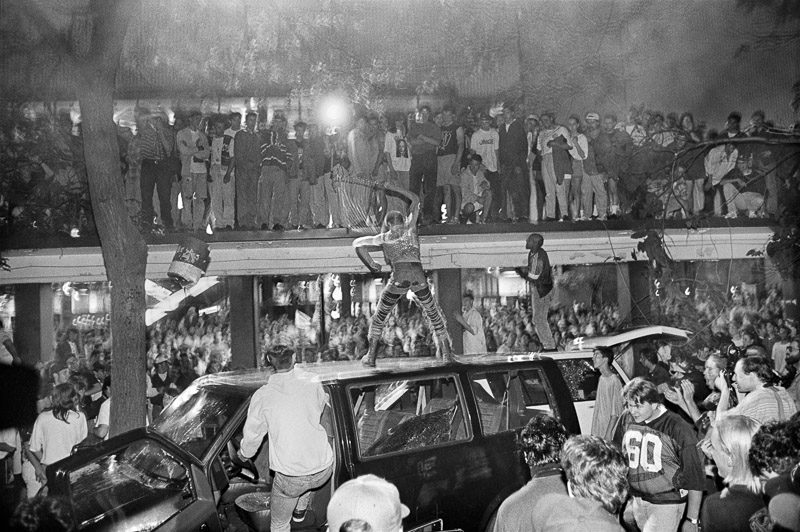

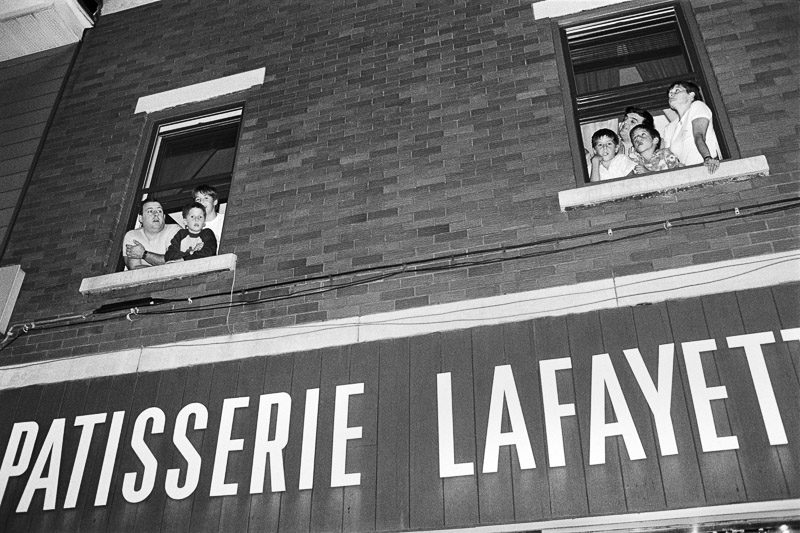

A consistent aspect of Leblanc’s approach to visual storytelling is his emphasis on spectators of an event rather than the event itself. Whether he is portraying a rodeo, a jazz concert, a procession, a fire, or a solar eclipse, he turns his camera toward the experiences and expressions of onlookers. “I like to look backstage,” he said. “To me, it is more interesting than the show itself.”

The parallels with pictures by American photographer Garry Winogrand taken on the streets of New York City a decade or two earlier are remarkable in respect to each photographer’s style of composing scenes and framing their subjects, as well as their fascination with radically different kinds of people and points of view occupying urban spaces in close proximity. From bingo players, street musicians, police officers, protestors, and porn stars to elderly Hasidic businessmen and Mohawk boys, Leblanc embraces the breadth of humanity in Montreal. Flash-lit photographs such as the one he took from the street looking up at children leaning out of a window to watch a fire also bring to mind WeeGee’s gritty scenes of New York at night sold to daily newspapers such as the New York Post.

Magnum Photos deeply influenced his work, according to Leblanc, who admires photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Sebastiao Salgado, and Eugene Smith. In 1987, he co-founded an independent photography agency, Agence Stock Photo, and he has worked as a freelance photojournalist throughout his career, covering a wide range of subjects outside of Quebec as well. For those who lived through Pope Jean Paul II’s visit in 1984, the Oka Crisis in 1990, Cardinal Léger’s funeral in 1991, the Montreal Canadiens’ Stanley Cup victory in 1993, and the Quebec referendum in 1995, Leblanc’s photographs of Montreal are likely to stir potent memories. For others, like me, who are curious about the city’s history or simply love good street photography, Leblanc’s body of work is a treasure trove and a rich cultural archive of a uniquely vibrant city near the end of the twentieth century.

Tema Stauffer is an American photographer, professor, and arts writer. Her work has been exhibited at Sasha Wolf, Daniel Cooney Fine Art, and Jen Bekman galleries in New York City, and in galleries and institutions internationally, including the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. She has contributed articles to PDNedu, American Photo Magazine, Culturehall, and other publications. Stauffer has taught at Concordia University in Montreal and schools in the United States. www.temastauffer.com