By Jill Glessing

Outsiders: American Photography and Film, 1950s–1980s

Art Gallery of Ontario

Curators: Sophie Hackett and Jim Shedden

The title that brings together the wild and woolly works in Outsiders: American Photography and Film, 1950s–1980s1 is worthy of consideration. The word “outside” depends on its semiotic partner in crime – “inside.” As these conjoined descriptors ripple through the exhibition, however, their edges soften and make visible the shifting nature of what is accepted, praised, marginalized, and shunned.

That these “outsiders” – drag queens, druggies, and dispossessed – largely mediated through documentary photography and experimental film, now grace walls usually reserved for blockbuster shows signals a revolution, at least in the art world. The ever-increasing value of photography and film for art collectors suggests that the historical struggle of these once-lowly mechanical media is now over. Sparking across these works are the dialectical clashes that advanced social and art history, bringing them to their “inside” status today.

Two artists in particular – Diane Arbus and Garry Winogrand – pushed this process along when, in 1967, they shared exhibition space in MoMA’s New Documents. For curator John Szarkowski, their work indicated a shift away from social reform photography and the photo essay, popularized by the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and LIFE Magazine, respectively. Those potent earlier forms – at once humanistic and didactic – stirred social change, while at the same time providing mass media entertainment.

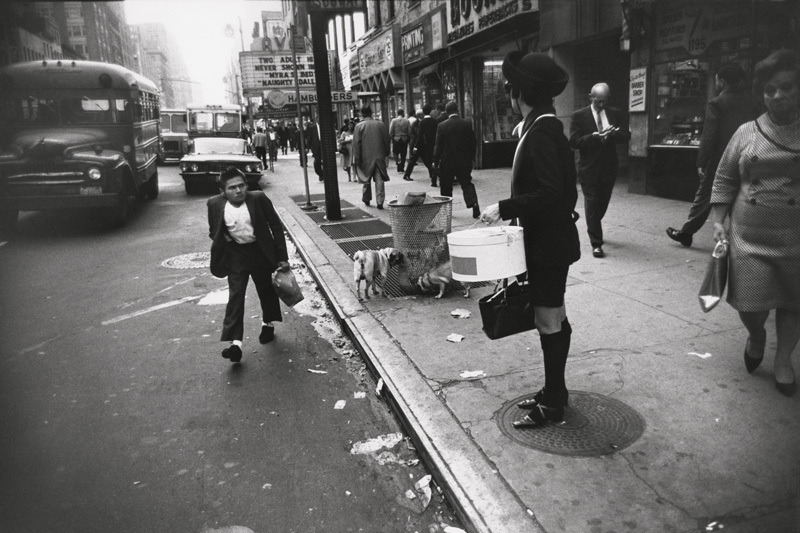

Tracking closer to European street photography, Sarkowski’s “new generation of documentary photographers” joined the tradition after Robert Frank cut critically into postwar American culture. Like his “decisive moment” precursor, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Garry Winogrand danced through crowds, but what he found and framed were not sweet slices of life, but social alienation and strife. Coming of age as America’s patina of prosperity was tarnishing, the new documentarians recorded the real world but did so to pursue their own personal obsessions in an increasingly strange world. Their marginalized subjects fascinate mainstream viewers, but their own motivations are equally interesting. The photographers’ entry into the documentary frame affirmed photography’s constructed nature and put a dent in its truth-value.

Like Winogrand, Diane Arbus sought subjects in her New York City environs. But, unlike Winogrand’s subjects, who seemed unaware of his hyperactive presence, the “freaks” that attracted Arbus’s alarmingly intense gaze looked right back at her. A Winogrand image here shows her in action, clutching a flower stem in her teeth – offered perhaps by the peacenik whom she’s intent on photographing.

Arbus’s solid compositions lend stability to her off-centre subjects. Lighting style fuels the Arbus mystery: in some images, harsh flash suggests a critical perspective; in others, light plays lovingly around her subjects. In Russian Midget Friends (1963), warm sidelight caresses the subjects’ cozy home. Another living-room scene is infused with angelic morning light: a middle-aged woman sits genteelly on the edge of a sofa while her husband fills his easy chair. They look perfectly normal, but for their lack of clothing.

The weird to which Arbus was drawn included giants, transvestites, saliva-soaked losers of Diaper Derbies, and uncanny twins. Her photographic acts might have been interrogations: How do you survive here? Can I join your exile? Her deep look at the young man settled in shady grass in Jack Dracula (1961) reveals a body laced with tattoos. But, she also produced the weird: the subject in Child with a toy hand grenade (1962) looks insane clutching his would-be explosive, but seems ordinary in the remaining frames of her contact sheet, also presented here.

Concluding Arbus’s section are photographs of her last subjects – residents in homes for the mentally disabled. Segregated at the farthest outposts of normality, they embody perfect freedom and joy. Struck by rich evening light, a group, costumed in nightgowns and pirate masks, walk hand in hand on a hillside.

Providing insight into Arbus’s work is her statement “Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats.”2 About her final subjects Arbus wrote, “FINALLY what I’ve been searching for.”3

If Arbus is the deep soul of Outsiders, Winogrand occupies its chaotic centre. His black-and-white prints, most of them small, appear dwarfed in the largest gallery, an effect mitigated by their grid presentation, three rows high across a long wall. It was the AGO’s recent acquisition of 443 Winogrand prints that prompted this exhibition; offered here is a smorgasbord of about 100 images from the 20,000 rolls of film that the artist shot during his short lifetime.

Winogrand roamed the realms of high art and low street, capturing the masses and the famous, in parks, protests, banquet halls, and political scrums. His pictures catch those awkward exchanges between strangers in public space. In Central Park, New York (1971), the members of a nuclear family with cowboy-hatted boys stand in a row. Their entranced gaze seems to rest on a group of lounging hippies, who might look to them like visitors from another planet. Other pictures show the hippie-inflected fashions of socialites whose isolation remains intact even as they let loose at museum galas.

The alienation and absurdity of contemporary life seem most condensed in Winogrand’s Central Park Zoo pictures. Members of a family lean over a railing and stare down into a pool of water; just above the surface, a walrus’s sad face looks toward the viewer. In these lonely confrontations, lookers and looked-upon are aliens across impassable divides.

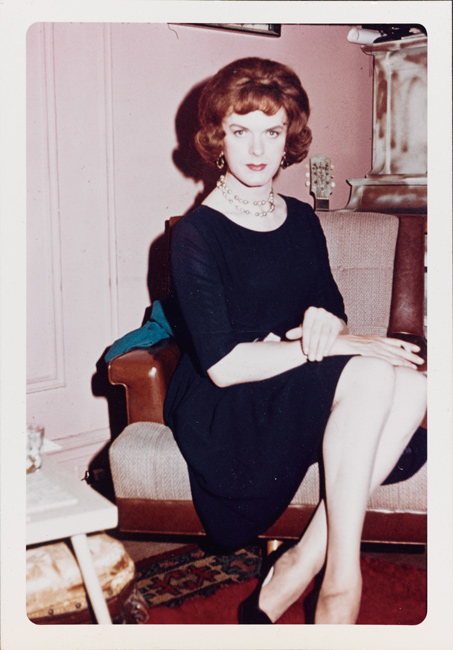

Adding further inspiration for Outsiders was another AGO acquisition – vernacular photographs taken of and by visitors at Casa Susana, an upstate New York resort where cross–dressers indulged safely in their fashion crimes. The snapshots are unique only in their greater attention to the magical details of dress that transform “he” into “she.”

Viewers become outsiders when they peek into Nan Goldin’s intimate world of parties, sex, and substance abuse during punk’s exuberance and AIDS-related decline. Her colour-saturated photographs – for example, the cover image of her book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1986), showing Nan and her gloomy boyfriend estranged on a bed awash in deep orange light – appear alongside her slide show of the same title. The thematically clustered images of friends living intensely pile into poignancy when paired with evocative period music. Goldin’s art invites voyeurs inside her nostalgia and loss.

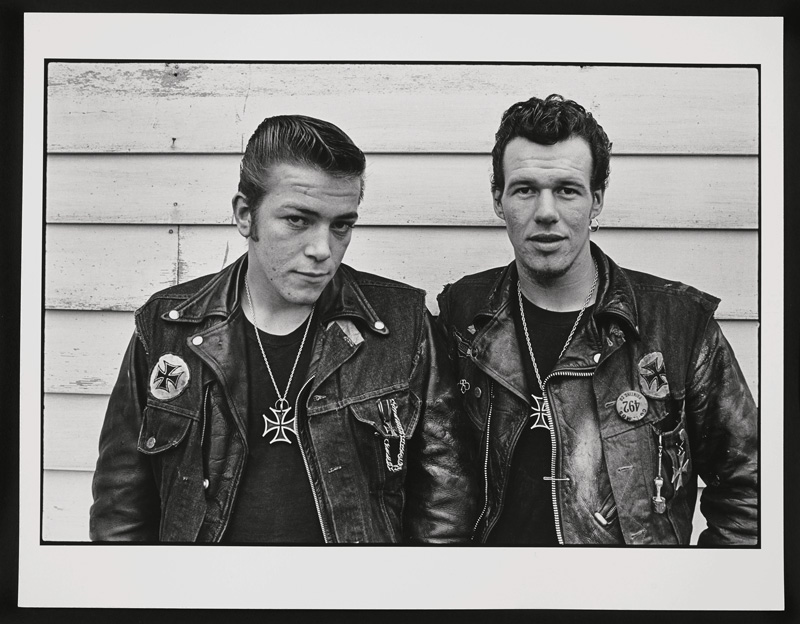

Along with other works here – Danny Lyon’s photographs of the Chicago Outlaw Motorcycle Club; Kenneth Anger’s deliciously subversive avant-garde film, Scorpio Rising (1964); the flickering filmic exuberance of Marie Menken’s Go! Go! Go! (1964) – the exhibition rings with the clatter of breaking boundaries.

2 Quoted in Frederick Gross, Diane Arbus’s 1960s: Auguries of Experience (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 133.

3 Wall text, Outsiders, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Sophie Hackett is associate curator of photography and Jim Shedden is manager of publishing at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Jill Glessing teaches at Ryerson University and writes on visual arts and culture.