By Élène Tremblay

Curator Joan Fontcuberta’s idea of bringing together artists who explore the post-photographic condition for this edition of Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal is especially pertinent in light of William J. Mitchell’s The Reconfigured Eye, published in 1992.1 We have clearly entered an era in which, as Mitchell underlined, digital technology not only has challenged both the status of the photographic image as document and the belief in its veracity, but has also modified its modes of production and reception. The proliferation of images made by amateurs on cell phones and immediately shared on the Internet, image search capabilities, and copying and pasting have had impacts that have yet to be investigated. This state of affairs corresponds, as Fontcuberta notes, to a second rupture or digital revolution, provoked by the appearance of social networks and mobile technologies.

In the post-photographic era, we consume images no longer on paper, but on various types of screens. The image is electronic, luminous, quickly replaced by another in a whirlpool of images. They come to us organized no longer only by artist or theme, but also by our navigation habits, displayed by search-engine algorithms. Not only are amateur photographs proliferating, but new genres and practices are being created and old genres are reinvented: the self-portrait has become the selfie, with its repeated “duck faces”; the slide show, remote-control tourism via Google Street View and Google Earth; photographs of what one eats in restaurants; obituary pages on Facebook, and much more.

Fontcuberta rightly posits that this proliferation of images – their production, publication, and appropriation by one and all – throws into question the notions of artwork and artist, as well as the authority of “image experts,” critics, curators, and professors, as Web users create their own groupings of images in Flickr, Instagram, Pinterest, Google, Facebook, and YouTube. His proposition explores all of these questions and refers us, through a mirror effect, to the world of images that we create and consume today. Most of the practices that he has brought together involve documentation on and collection of images existing on the Internet that take account of, problematize, and challenge these new uses and forms of presentation of photography.

Postmodernism had already opened a breach with the originality of the artwork, the notion of the author, and the interiority of modernism. Appropriation, pastiche, and parody were among the main strategies adopted by artists in the face of marketization of images and art objects. The postmodern artist no longer produced original images, but borrowed images upon which to perform critical commentary. Today, artists, like the public, are navigators in a sea of online images. The Internet becomes their means of access to the world, and their search tools shape and orient this access. Given the high “appropriability”2 of Web content, borrowing is now one of the most easily executed gestures that Web surfers can perform.

Although many of the artists in the biennale choose to mimetically reproduce this overabundance and rapid circulation of images by proposing a dystopian vision of the situation, others are more interested in following how images displayed by Internet search engines are received and organized, while expressing a concern with preservation of these images and access to their content. I find the latter propositions more stimulating. I’m thinking of the works by Joachim Schmid, Erik Kessels, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, Roy Arden, Sean Snyder, and Paul Wong, as well as, for their ethnographic qualities, the projects by the collective After Faceb00k and Laia Abril.

All of those in the first group seem to make the same observation: there is a profusion, an overabundance, of images. Although this observation is just, it is a rather slim premise taken on its own. Artists choosing to limit themselves to it present images in uncountable, and sometimes opaque, masses that leave us at their threshold, without a truly significant way in. For instance, the hundreds of videos assembled by Christopher Baker in the form of a large multi-projection mural showing people addressing their webcams in Hello World! or: How I Learned to Stop Listening and Love the Noise (2008) do not give us access to these testimonials, as the sound track is miserly in this regard. Similarly, the assemblage by Hans Eijkelboom of images of hundreds of passers-by as a function of the similarity of what they are wearing seems insubstantial, as do the grids of images from the Internet and organized by similarities by Dina Kelberman, who imitates, without comment, the scrolling of results of image searches via a search engine.

The second group of artists do not limit themselves to performing simple mimetic work but reflect on the organization and nature of images on the Internet by using displacement strategies – transfers to other forms and media. For Schmid, this entails a return to printed books; for Kessels, to postcards; and for Broomberg and Chanarin, to paper, in the form of Bible pages on which they underline the text. Arden created a slide show accompanied by music, and Wong created rhythmic graphic animations. Finally, Snyder transferred images to multiple media; After Faceb00k, into an installation.

The works by these artists make it possible to reconnect the fragments disseminated in the current world of complexity and profusion by encouraging analysis of their content. For instance, Schmid organizes the most trivial images gathered from a search by keywords on the Internet and transfers them in a very interesting fashion into ninety-six small books. As a bulimic collector, an ironic visual anthropologist, he gathers his images on photo-sharing sites such as Flickr, puts them in order, and returns them to the public. Each book in the Other People’s Photographs collection bears a title describing the images that it contains – Black Bulls, Trophies, Airline Meals, Encounters, Food, Sunset, and so on; we can sense here a nod to Edward Ruscha’s famous book Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963). These themes reveal the habits and preferred subjects of today’s amateur photographers. Visitors are invited to consult these small books, arranged in alphabetical order on long tables, and discover what is hidden within their uniform grey covers. Books, today threatened by tablets and e-readers, regain their value here in the obvious pleasure that visitors take in leafing through them.

Kessels similarly collects and organizes found images. In the installation All Yours, dozens of postcard display racks occupy an entire gallery, making the space look like a store. Each display rack brings together images gleaned here and there, in flea markets, around a single theme: women in bathing suits at the beach, Dalmatian dogs, deer, and so on. Playful and rewarding for visitors, Kessels’s and Schmid’s projects complement each other.

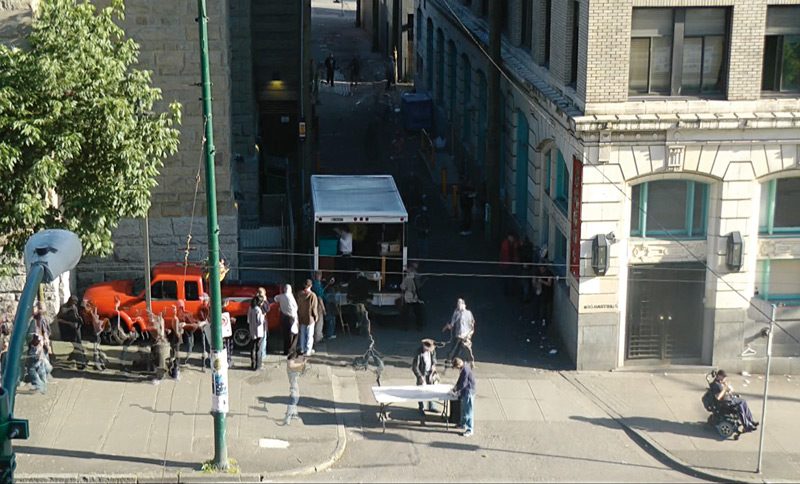

In Arden’s The World as Will and Representation – Archive 2007 (2007), the assemblage of heterogeneous images into themes takes the form of a digital slide show on a small screen; the slides scroll by to the regular beat of elevator music punctuated by brief piercing, repetitive passages. This music and the triviality of the images give an ironic tone to the artwork. The rate at which the slides display allows us to distinguish each of the 28,144 edifying images. The roots of such a project lie in the old-style slide show, which is revisited by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller in Road Trip, also presented in Le Mois de la Photo.

Although rapid, the jerky pace of the animated GIFs – the short animations that loop on Web sites – produced by Wong nevertheless allow for a reading of their varied content: self-portraits, architectures, urban views, colours, lines, screens. This is a creative appropriation of the form, peculiar to the Web, of the animated GIF to make original works that document the artist’s physical paths through the city and his virtual paths on the Internet. Their assembly in clusters, with short videos, produces a visually highly loaded ensemble that excites the gaze just as the Web may do.

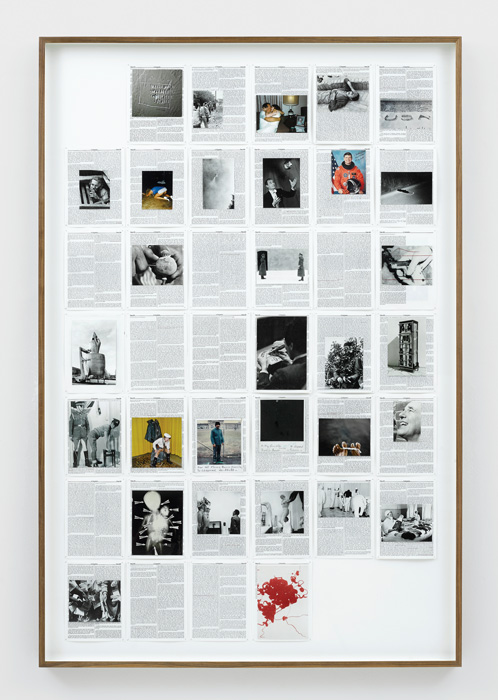

Broomberg and Chanarin have created an allegorical work in which found photographs dialogue with words underlined by hand in the Bible – underlining that is reminiscent of hyperlinks – somewhat similar to what Bertolt Brecht did in his annotated version. The violence of the biblical text associated with the violence of humans and their institutions – represented in photographs of catastrophes, war wounded, pornography, and humiliation practices – produces a wide-ranging portrait of power relations, past and present. Whereas catastrophes are constantly covered in the media and often seized upon in religious discourses, biblical themes such as sin, desire, and great calamities inflicted by God as collective punishment are brought into focus when placed in relation to images.

The critical and political position of hunting down ideological deviations and slippages is developed meticulously in Snyder’s analysis of the media, their discourses, and the economic forces that influence them. In his work Casio, Seiko, Sheraton, Toyota, Mars he flushes out brands and consumer products in the context of recent wars and conflicts and challenges the role of photojournalists, and in Aleatoric Collision (Sony Hacking Scandal) he points out Sony’s product placements in the film The Interview as well as the discourses of paranoia that accompanied them. In a similar register, Blain uses images of large demonstrations and popular uprisings in recent years to highlight, from mass movements and the anonymity of the crowd, the faces of individuals moved by anger and passion.

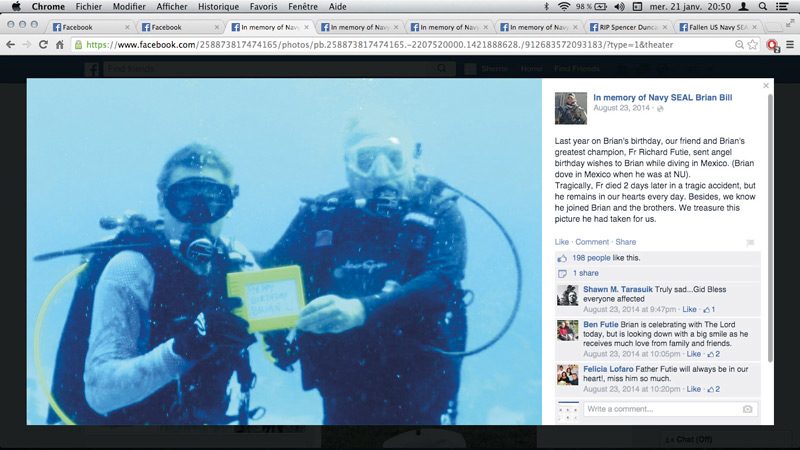

The collective After Faceb00k takes an ethnographic look at the Internet with its project À la douce mémoire <3, in which it documents a new memorial custom in the era of social networks: commemorative Facebook pages for deceased people – and pets. Through screen captures, the collective grabs pages featuring images of coffins, flowers, graves, balloons, and sometimes even cadavers, thus reviving the early-twentieth-century practice of post-mortem photography. The digital space for conservation of these pages is presented as a digital cemetery, with the servers becoming funerary steles in which are buried thousands of images disseminated on screens placed on the ceiling. In her series Thinspiration, Laia Abril also conducts ethnographic research – in her case, into the world of anorexics, by collecting the self-portraits of deliberately emaciated people published on the Internet.

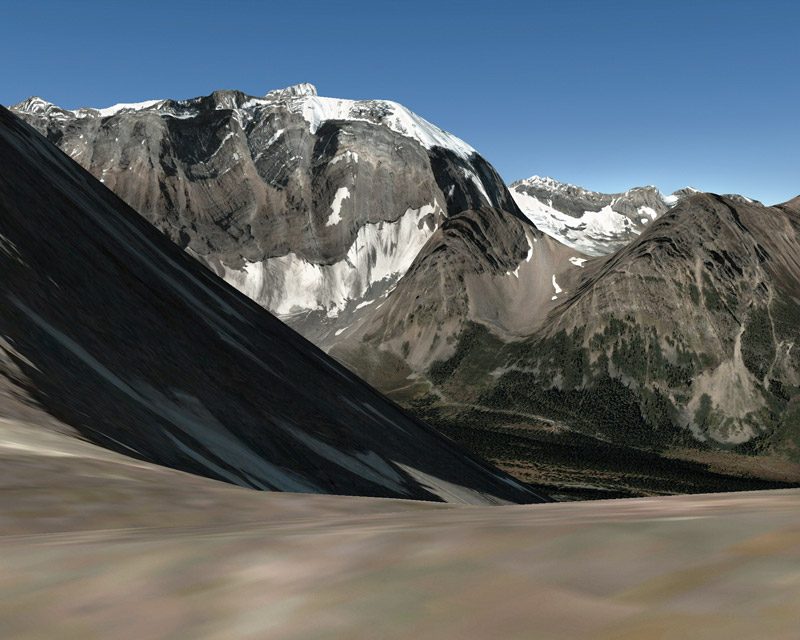

Among the few artists in the biennale who still produce original images – this low number being symptomatic of the post-photographic condition – two of them, Andreas Rutkauskas and Leandro Berra, study the comparison between photographs that they have made and images produced by software or via satellites. Rutkauskas’s works ask whether it is still necessary to leave home to discover the world when Google Earth enables us to visit distant sites – a question asked by all artists in this biennale who find their images on the Internet. In Virtually There, Rutkauskas compares images of the Rockies produced by Google Earth and those that he took of the same sites. The comparison is revealing, as the Google Earth images delete important details, reducing jagged relief features to straight lines and areas of shadow to dark masses. Beside them, Rutkauskas’s photographs appear rich and detailed.

The comparison made by Berra reveals the approximate nature of automated portraits made with Faces, a software package used by forensic police to reconstruct the faces of criminals from witness accounts. The artist diverts the software to a different use, that of the self-portrait. Having asked various people to reconstruct their own faces from memory and also having photographed them, Berra juxtaposes the two types of images. Major differences arise between the reality and the synthetic image produced by the software, and it is these differences – due no doubt to the individuals’ perceptions of themselves, but also to the limitations of the tool – that are of interest. In the work of both Rutkauskas and Berra, the reductive, crude nature of representations made by software and satellites, to which we are prepared to adapt, becomes obvious when placed next to the precision of photographs.

In short, this edition of Le Mois de la Photo and its curator add a new chapter to thought about the state of photography today. The central point that emerges from all of the exhibitions is the fundamental transformation in the mode of capturing images, which is based no longer on the photographer’s physical presence in situ, but on expert navigation of the Internet. As a consequence, the artistic gestures made are related mainly to appropriation, collection, and organization of found images, and works are produced through critical, systemic, allegorical, and ethnographic approaches. Visitors find significance in these overviews, which encourage a position of analysis and critical reception.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 See André Gunthert, “L’œuvre d’art à l’ère de son appropriabilité numérique,” Les carnets du BAL, no. 2 (October 2011): 136–49, http:// culturevisuelle.org/icones/2191.

Élène Tremblay has been an assistant professor in the Department of Art History and Cinema Studies at the Université de Montréal since 2011. She earned her master’s degree in visual arts from Concordia University in Montreal in 1996 and a doctorate in art studies and practice from the Université du Québec à Montréal in 2010. In 2013, Éditions Forum, in Udine, Italy, published her book L’insistance du regard sur le corps éprouvé. Pathos et contre-pathos.