Prefix Institute of Contemporary Art in partnership with A Space Gallery,

Toronto May–July, 2015

By Blake Fitzpatrick

The rupturing effects of global change – as epitomized recently by news stories about migrants in over-crowded boats, with bodies on deck, in the hull, and in the sea – come to roost at the local level, where the risks of globalization are most exposed but also potentially transformed through acts of resistance. Artist Yto Barrada works in Tangier, Morocco, a city located on the North African coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, what Barrada calls “a jumping-off place”1 in the global flow of the dispossessed travelling north from Africa to Europe. Barrada’s exhibition Beaux Gestes, presented by the Prefix Institute of Contemporary Art and A Space Gallery in Toronto during the Scotiabank Contact Photography Festival, interprets the effects of modernization and the global economy on locality. In her photographic and video work, Barrada turns her camera to the vernacular, finding in vacant lots, playgrounds, palm trees, and the indigenous botany of the region a range of subjects with which to invent a visual “grammar of Tangier.”2 She pays quiet attention to the local and, in solidarity with the indigenous, draws our attention to minor sites of resistance in a transitional geopolitical landscape.

In this dual-venue exhibition, a mix of video installations, photographs, and posters combine to produce a parallel depiction of a city that is itself composed of fragments, loosely associated pieces, and contradictions. As Hamza Walker writes in the issue of Prefix Photo that accompanies the exhibition, “Barrada’s images, as much as they are about a place, are also a portrait of a condition.”3

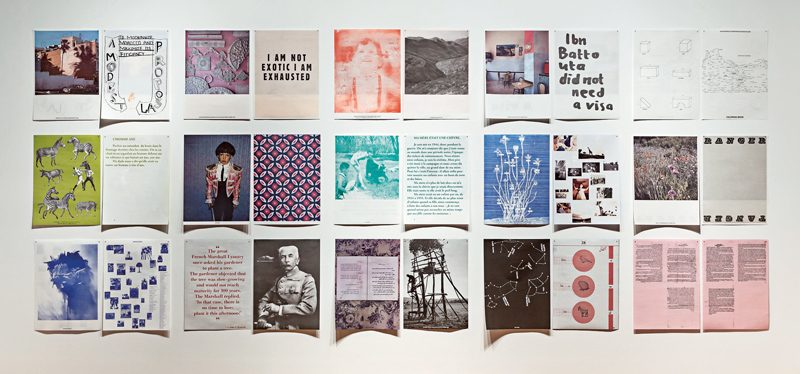

The range of image modes evident at Prefix included a film transferred to video, Hand-Me-Downs (2011); a single colour photograph, Sheep Market Day, Val Fleuri (2007); and a series of fifteen posters titled A Modest Proposal (2010). Childlike in execution, the posters reference the region in an idiosyncratic collection of maps, photographs, and encyclopedic entries of local flora and fauna. A hand-drawn title poster proclaiming “A Modest Proposal to Modernize Morocco and Maximize Its Efficiency” satirically comments upon and undermines notions of progress that are driving an increasingly privatized and internationalized country at odds with the traditional market economy depicted in the nearby documentary photograph, Sheep Market Day. In this component of the exhibition, intelligently curated by Scott McLeod and Vicky Moufawad-Paul, the juxtaposition of these works extends a critical dialogue between various images of the region and diverse media forms.

The aforementioned Hand-Me-Downs (2011) is a filmic installation of narrated footage from the 1950 to the 1970s drawn from the Cinémémoire, a Marseille-based archive of amateur films from former French colonies. Barrada’s reference to the hand-medown speaks not only of clothes passed down from one generation to the next but of family stories passed down as well. In a playful way, the work quotes the autobiographic conventions of home movies and the film essay as fifteen numbered chapters unfold, held together by Barrada’s voiceover. In a voice of recollection, informed by her mother’s childhood and connected to a series of darkly humorous, even sardonic episodes, unverifiable stories of familial events are tied to disparate film fragments from a colonial past. As viewers, we seek to find a connection between word and image, a desire that Barrada both loosely fulfils and confounds. Perhaps what is revealed in this piece is not only our vulnerability to the seduction of cinematic narration but a provoked failure within the form to build an illusionistic whole out of the isolated fragments of contemporary life as cast apart by colonial history.

The component of the exhibition at A Space Gallery included Playground (2010), a three-channel 16 mm film transferred to video; images from the photographic series Iris Tingitana (2007); and Beaux Gestes (2009), a three-minute single-channel 16 mm film transferred to video. Playground (2010) is a silent, twenty-one-minute video installation that unfolds across three screens, depicting a compendium of quotidian acts in transitional spaces. The choice of a multi-channel projection is important as it calls for a type of ambient spectatorship, not directed to a particular image in time. Here, children play in a make-shift playground; anonymous bodies on green grass are suspended in sleep; men dig in the soil to plant seedlings; and sheep graze in fields that are dotted with the vivid blue of wild irises framed by construction sites and concrete buildings. An eerie quietude hangs over the work, as the loss of sound and the depiction of filmic devices, including the film gage and scratched emulsion, draw a parallel between an obsolescent recording technology and the transformation of the local in a landscape earmarked for redevelopment. Barrada refuses viewers the comfort of nostalgia, insisting that we regard the traces of the indigenous as survivors in a politically charged landscape. These tensions are apparent in the photographic series Iris Tingitana (2007), in which deceptively ambiguous photographs are composed specifically to direct attention to what might next be lost. The focus is on the iris as one of Tangier’s native plants: the flower is seen in pastoral fields as well as in unregulated spaces, rooted next to roadways and housing projects, holding on at the edge of encroaching urbanization. As symbol, the iris is a witness to change, its survival an act of resistance.

Botany and what Barrada calls “strategies of resistance”4 mix most explicitly in Beaux Gestes (2009). The piece begins with an aerial shot of the city and the patchwork of vacant lots that rim its perimeter. At ground level, a group of men attend to a palm tree with a deep cut at its base. The cut has been intentionally inflicted on the tree by a developer, who is unable to build on the land while the tree is alive. The men are engaged in an act of preservation aimed at staving off the ravages of urban development. The act is one of resistance, and it parallels the work of the camera in putting a halt on time. Acts of resistance are often hopeful gestures. In this case, the hope is that change can be negotiated, that the process can be slowed, and that the tree as witness will survive.

2 Ibid.

3 Hamza Walker, “Beaux Gestes: On the Photographs of Yto Barrada,” Prefix Photo, no. 31 (May 2015): 48.

4 Barrada and Higgie, “Talking Pictures.”

Blake Fitzpatrick is a photographer, curator, and writer and a professor in the School of Image Arts at Ryerson University. His research interests include the photographic representation of the nuclear era, visual responses to contemporary militarism, and the history, memory, and mobility of the Berlin Wall. His curatorial projects examine the representation of war and conflict in documentary photography, and his writings and visual works have been published and exhibited in Canada and Europe.