[Summer 2010]

by Claude Baillargeon

The Malcolmson collection

A passion for photography

Claude Baillargeon: Before you began to nurture your passion for photography, you were avid collectors of contemporary art, especially painting. What led you from one discipline to the other and from contemporary to historical works ?

Ann Malcolmson: In 1985 we moved to a smaller space, and so big paintings were no longer practical. While in New York, we saw early examples of photo-based art, like that of Craigie Horsfield. Although much of it was too big for us to manage, we became fascinated by the history of the pictures that lay behind this new interest in using photography as a basis for art.

Harry Malcolmson: We were also a product of the 1970s, the period when collecting historical photography originated with the development of an infrastructure of galleries, dealers, and auction houses. In Toronto, we were exposed to historical photography through Jane Corkin, who opened a photography space within the David Mirvish Gallery. I had a sense then that there was something in historical photography, which I could not yet identify, that we would come to find very attractive. The further involved we became, the more rewarded we were, and this confirmed the sense we had that there were wonderful things to discover.

AM: Harry also felt that we might be able to afford some excellent pieces of historical photography at a time when prices for contemporary art were rising sharply.

HM: That’s true, but first we had to confirm that this was a worthy and rewarding area. We started with the kind of apprehension that everyone has when thinking about collecting photographs.

CB: When did you first recognize that you had become photography collectors ?

HM: In 1990 or thereabouts, Jane Corkin had auctions at her gallery. On one such occasion, we were so taken by the wonderful range of works that we acquired about half of them. They were so beautiful and inexpensive. We just scooped them up. Having said that, the crossover from acquiring photographs to building a collection was when we decided to donate all of our non-photographic artworks.

(…) we aim to have representative works from all of the main phases of the history of photography.

AM: Even though we had a lot of paintings, we always did like works on paper very much. We were fairly quick to give our paintings to various institutions, but the works that we held onto the longest were works on paper, such as prints by Richard Hamilton, James Rosenquist, and Richard Serra. So that love of paper is something I’ve had throughout.

CB: What was the first major acquisition that confirmed your commitment to photography, and what made it irresistible ?

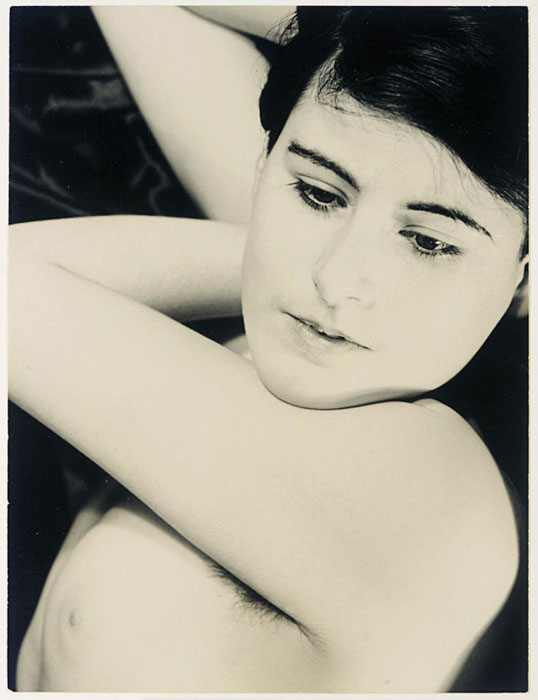

AM: I would say the untitled piece by Man Ray of the woman’s eyes that combines drawing and photography. That work had a mystery to it that was totally fascinating. It was and remains a mystery as to when it was done, why it was done, and what may have led Man Ray to touch it up in pencil. The history surrounding that work is something that has fascinated us for years. This was a major step in our collecting.

HM: For me, there was no eureka moment. The interest was part of a continuum. Since the 1960s, when I wrote art criticism, my personal aesthetic perspectives have been sustained. I view the shift to photography within our collecting process as simply an instance along that continuum.

CB: With so many images to choose from on the market, what criteria have you developed to guide your collecting ?

HM: One criterion is defined by the temporal parameters of the collection, which range from William Henry Fox Talbot to Robert Frank, though we allow ourselves the occasional “slippage” into contemporary photography. As we have a historical collection, we aim to have representative works from all of the main phases of the history of photography.

AM: Along with these guidelines, aesthetic excellence is the basic quality that we look for. Beyond that, there are issues of condition, paper quality, patina, and so on. The importance of specific figures within the history of the medium also informs our collecting, as do relationships among works.

CB: Private collections often evolve in unexpected ways. What fortuitous acquisitions have you made that later played pivotal roles in the growth of your collection ?

AM: One example would be Édouard Baldus’s Château of Princess Mathilde, Enghien (1854–55), which was among our first nineteenth-century acquisitions. To this day it remains one of my favourites. The fact that it was such an attractive and important photograph brought into greater focus our growing interest in French photography from the 1850s and 1860s.

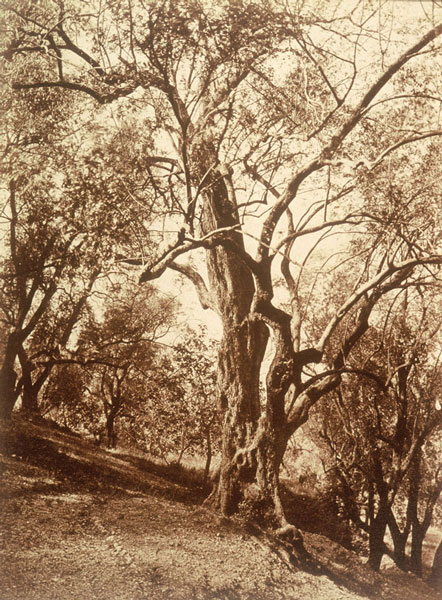

HM: Another early acquisition that proved influential was Auguste Salzmann’s Jaffa Gate, Jerusalem (1854), which is a remarkably modernist picture with its strong contrast of light and shade. At a time when photographs were mostly descriptive and documentary, Salzmann achieved an image with an aesthetic character that was closer to painting than to photography, and this anomaly resonated with my sensibility.

CB: What are some of the most distinctive threads that you have woven together over the years ?

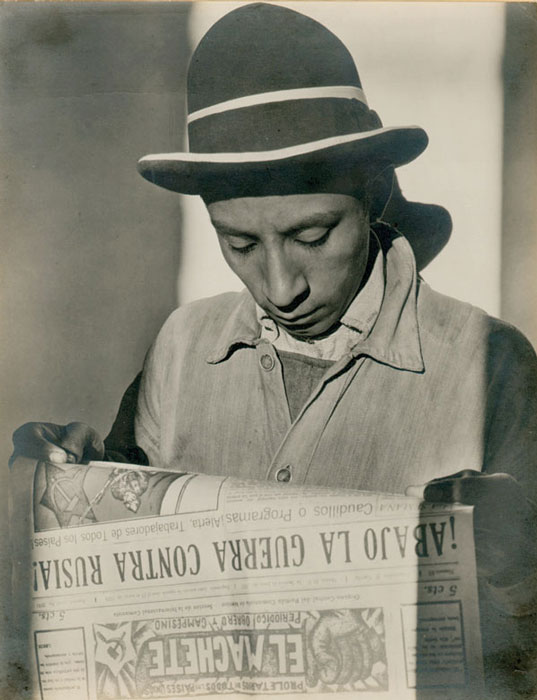

HM: One stream has been our interest in making substantial investments in the most historically important photographers, such as André Kertész, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Man Ray, Bill Brandt, Tina Modotti, and Robert Frank, for whom we have at least five significant images apiece.

AM: One thing I love in photographs is mystery, the je ne sais quoi that is perhaps most evident in surrealist works, but that can also be found in several other photographs that ask more questions than they answer. I like that quality of being invited to go into a photograph and explore what it’s asking.

CB: You have recently begun to acquire contemporary colour photographs by Canadian artists. What is driving this selective broadening of the collection beyond its historical core ?

AM: The contemporary work comes out of an interest in the relationship between what the contemporary artists are doing and what the historical photographers were doing. For instance, one of our works by Ian Wallace, Le Passage d’Enfer, Paris (2008), closely relates to our street photographs of Paris taken by Charles Marville in the 1860s. Similar relationships inform most of our contemporary acquisitions.

CB: Is this a new focus for the collection ?

HM: I don’t think so. It isn’t as if we are now seeking to buy contemporary photography. Our commitment to historical photography is as strong as it ever was.

CB: Since you collect as a couple, how do you negotiate each other’s aesthetic preferences ?

AM: What Harry brings to the mix is an experienced eye and a deep knowledge of art, whereas my contribution taps into a penchant for emotional response and greater sensitivity to print quality. During one of our visits to Paris, my persistence, despite Harry’s initial reluctance, led to the acquisition of an equine picture from the 1850s by Jean-Baptiste Frénet. As Harry knows, I was longing for this photograph not because of its subject, but because I love this salted-paper print for its tone, its textural quality, and the visual evidence of chemical remnants embedded in the very fabric of the image. In fact we have two salt prints of equines, this horse by Frénet and a donkey by Adrien Tournachon, both of which I love for their visual tactility.

HM: In the end, the Frénet picture did make for a wonderful surprise birthday present.

CB: With so few opportunities to view curated selections of your collection, did the recent showing at Presentation House Gallery make you see some aspects of it in a new light ?

HM: Frankly, the acclaim and enthusiasm took us aback and, because it was all on the walls, gave us a sense of what we have accomplished that would not otherwise be apparent to us. For one thing, we were amazed how many pictures there were and our reaction was “Good Lord, look how many there are.”

AM: My reaction was what a good job Helga Pakasaar had done in finding relationships that we had not previously found. That was really the fun part for me, because we’ve always been interested in the relationships from one work to another, but Helga brought out new ones.

Claude Baillargeon is an associate professor of art and art history at Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan. He received his PhD from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and his MFA from The School of the Art Institute, Chicago. His most recent curatorial projects include Revolutionizing Cultural Identity: Photography and the Changing Face of Immigration (2008) and Imaging a Shattering Earth: Contemporary Photography and the Environmental Debate (a five-venue travelling exhibition on view at the National Gallery of Canada in 2008).