[Spring/Summer 2011]

by Dayna McLeod

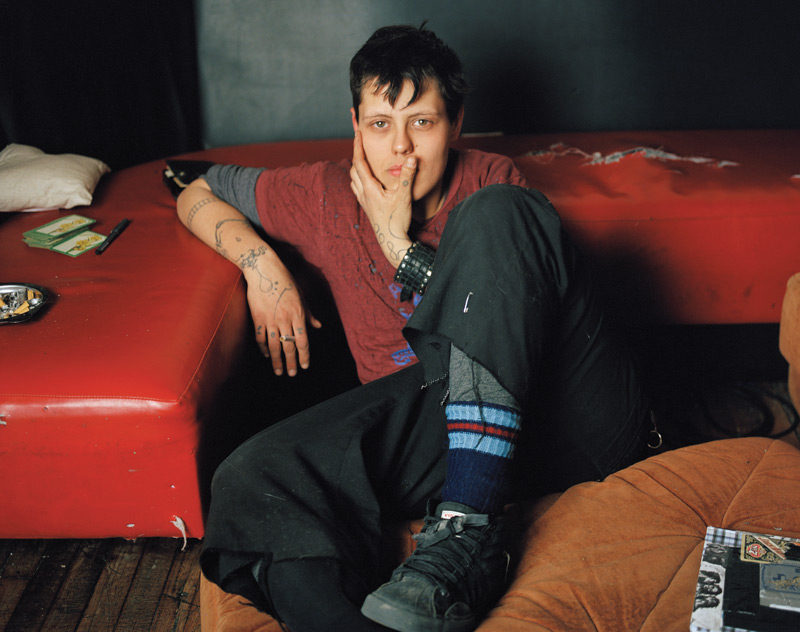

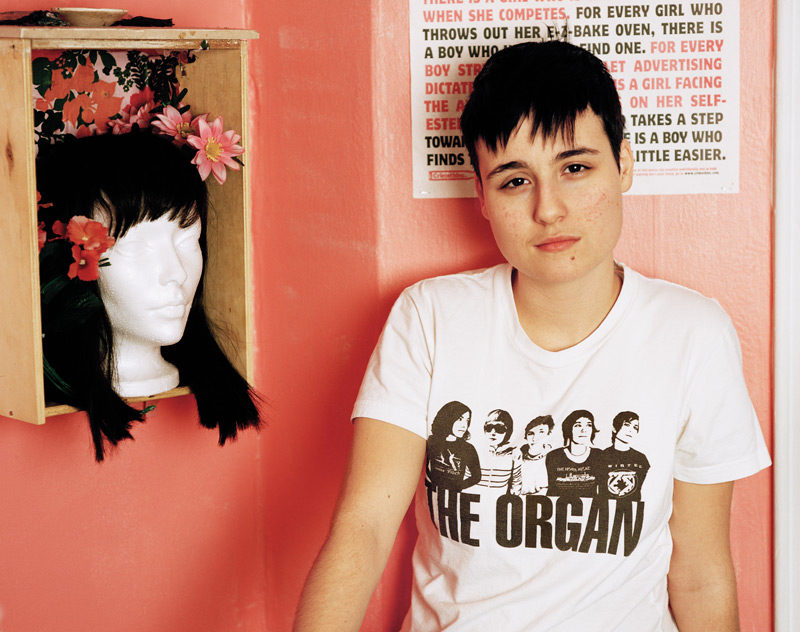

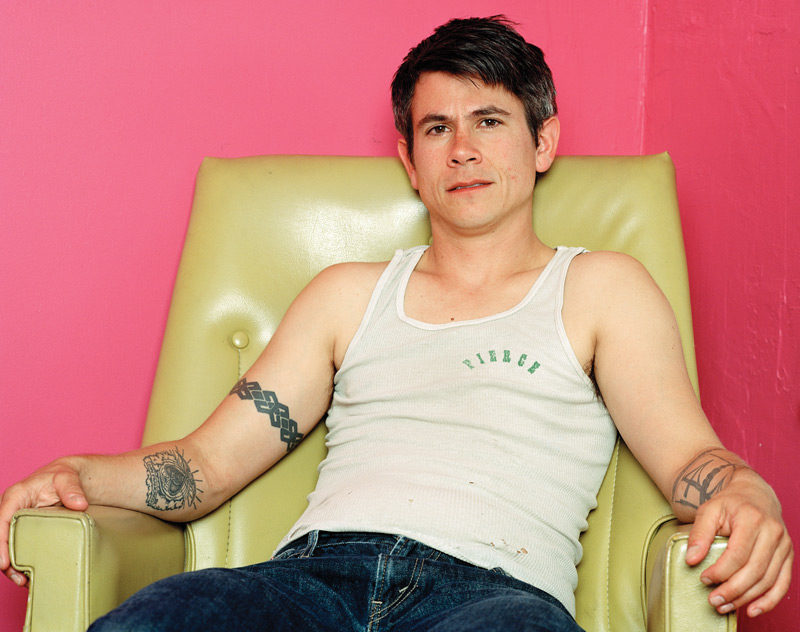

Vivid colours and rich, symbolic domestic detailing underscore the confident, self-possessed gazes of J J Levine’s subjects in their series Queer Portraits. An exploration of identity, gender politics, community, public vs. private, radical queer life, and deviant gender presentations, Queer Portraits confronts us with a group of subjects that ultimately reflect a portrait of the artist themselves. An intimate look at Levine’s community, this series plays with traditional portraiture, symbolism, composition, and non-normative gender presentations. Levine’s subjects are captured in their home environments; these domestic spaces speak secrets and volumes about the personality of each subject and Levine’s relationship with them by hinting at a coded symbolic order reminiscent of traditional portraiture. They use both vibrant and muted colours, line, shape, and pattern to frame an intimacy with their subjects for the viewer’s pleasure that is simultaneously complemented and complicated by their subjects’ unwavering gaze.

In Johnny Forever, Levine’s subject stares at the viewer in a casually confident pose filled with purpose. Dressed in gold leggings and a delicate cream-on-cream patterned blouse, Johnny Forever’s legs are tucked under their body on a plush gold couch, the left arm casually draped over it, the other arm holding their body upright in a firm posture. Gold chains and costume jewellery hang from the wall to the left of the subject as home decoration, and a black-and-white rectangular image behind the subject reinforces the shape and form of the photographic frame itself. As in other images within the Queer Portraits series, these kinds of details, including the comfy home environment, speak to the personality of the subject and symbolically represent the trusting, intimate relationship between subject and photographer because of their inherent meaning to both. Johnny Forever balances rich and warm gold tones that seem to radiate from the subject, drawing us further into the frame and into this relationship. Zoe is an emotionally charged portrait that features Levine’s subject with their dog as they stare defiantly at the viewer, while Nathan, Danielle, Hank, Aman, and Ej are portraits of subjects not self-consciously quoting or performing androgyny, masculinity, or femininity, but instead offering a broad spectrum of queer identity that represents the complex relationship that we have as viewers with coding and decoding non-normative gendered bodies that exist outside of a heteronormative matrix. By capturing and showing these intimate portraits, Levine makes the private public, exposing private queer space to the public sphere.

All of the images within Queer Portraits have a photographic truth to them; Levine’s subjects are living their bodies and fulfilling identities that are potentially marginalized and/or theatricalized within mainstream culture; within their own community, however, they simply are. Each portrait communicates an individual, but as a collection the images become a community, a potentially politicized representation of a radical queer community steeped in gender politics. Likewise, these portraits demon-strate an emotional connection between the subject and Levine as the photographer; there is an evident element of trust that is integral to each image and its strength as a portrait. Within this series, Levine brings the private queer life – not a secret, shameful life, but an often-marginalized expression of genders and sexualities within a mainstream context – to the public sphere. As Butler writes, “The subject who is ‘queered’ into public discourse through homophobic interpellations of various kinds takes up or cites that very term as the discursive basis for an opposition. This kind of citation will emerge as theatrical to the extent that it mimes and renders hyperbolic the discursive convention that it also reverses.”1 Within this general public sphere, the queer body is performed whether it likes it or not, whether it intends it or not, and Levine’s very act of composing, capturing, and collecting these images for general public consumption becomes a queer political action that emphasizes the visibility and presence of a queer community and its members within a public space. Queer visibility becomes both a political and a theatrical action because of the context of the display and the very queerness of the content. Queerness cannot escape spectacle in the public realm because heteronorma-tivity insists on its theatricality, while homonorma-tivity dismisses non-normative gendered bodies for its survival within this same public sphere. Homo-normativity “aim[s] at securing privilege for gender-normative gays and lesbians based on adherence to dominant cultural constructions of gender, and it diminishe[s] the scope of potential resistance to oppression.”2

… portraits of subjects not self-consciously quoting or performing androgyny, masculinity, or femininity, but instead offering a broad spectrum of queer identity …

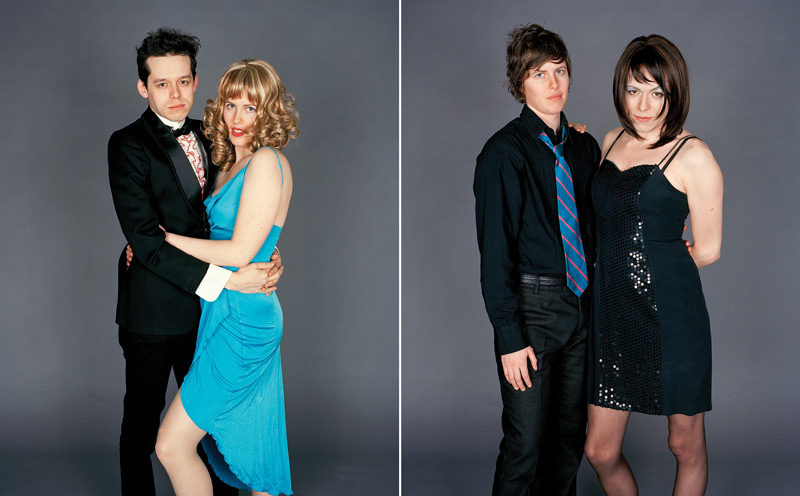

While the images in Queer Portraits rely on photographic truth, Switch and Alone Time question the authenticity of the photographic image through its manipulation. These series capitalize on heterosexual constructions of gender identity and quote masculine and feminine codes of performativity to challenge our participation in and acceptance of heteronormative culture, behaviour, and spectacle. Alone Time twins a single subject into a gendered binary pair within an intimate home setting – kitchen, bathroom, bedroom, living room – and capitalizes on heterosexual stereotypes of domestic nesting. Switch also features “heterosexual” couples, only this time, their images are captured in the convention of prom photography. Subjects are dressed to the nines in formal evening wear; they happily project binary masculine/feminine roles of gender stereotypes, playfully posing with their arms around each other, smiles beaming as they engage in the obvious codes of this heterosexual ritual. At first glance, Levine’s diptychs picture two separate couples. Upon closer inspection, however, we see that these images are not of four different people, but of two people who are performing gender stereotypes. Twice. And it is this dual performance, this seamless performativity of each role, that delights and confuses the viewer. Which role is authentic? Which gender role is the “real” subject? This performance disrupts the heteronormative spectacle and calls into question the very construction of masculine and feminine identities and their traditional binary scripts in which “‘normal’ and ‘heterosexual’ are understood as synonymous”3 as well as their reliance on extreme codes of what constitutes feminine and masculine. Sequins, sparkles, chintz, satin, high-maintenance hairdos, and make-up dress the feminine, while sombre suits, ties, and slicked-back hair dress the masculine in Switch. Alone Time also reflects a traditional binary code of dress that emphasizes masculine and feminine stereotypes. But the success of Levine’s couples’ performativity in both Switch and Alone Time is not merely cosmetic; their heterosexual passing is also coded through posture, gesture, and attitude. While Levine’s subjects’ drag reveals the cracks in heteronormative assumptions and privilege in which “het[erosexual] culture thinks of itself as the elemental form of human association, as the very model of intergender relations, as the indivisible basis of all community, and as the means of reproduction without which society wouldn’t exist,”4 these portraits are further complicated within a homonormative structure. Levine’s subjects’ gender performa-tivity disrupts homonormative biases of identity and essentialist views of what constitutes a queer body. Why are these non-gender-normative bodies rele-gated to heterosexual disguise? The answer lies between the lines, in the form of yet more questions: Why perform heterosexuality at all, and why does heterosexuality need a costume? Once we, as viewers, recognize these gender performances as performance, we become stuck in a comparative loop contained within each image, scrutinizing and analyzing every aspect of dress, attitude, and presentation, unravelling these costumes and their affects until our gaze is reflected back to us in the ultimate social mirror, leading us to question our own participation in binary gender construction, heteronormative behaviour, and homonormative exclusivity.

2 Susan Stryker, “Transgender History, Homonormativity, and Disciplinarity,” Radical History Review, 100 (Winter 2008), 147.

3 Dennis Sumara and Brent Davis, “Interrupting Heteronormativity: Toward a Queer Curriculum,” Curriculum Inquiry, Vol. 29 No. 2 (1999), 202.

4 Michael Warner, Fear Of A Queer Planet: Queer Politics and Social Theory

(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), xxi.

JJ Levine is a Montreal-based artist who works in intimate portraiture. In 2008, Levine completed a BFA in photography at Concordia University, with a minor in interdisciplinary studies in sexuality from a fine arts perspective. Levine’s photography explores issues surrounding gender, sexuality, self-identity, and queer space. Two of Levine’s recent bodies of work, Queer Portraits and Switch, have been exhibited at artist-run centres and commercial galleries across Canada, the United States, and Europe. Levine’s art practice balances a political agenda with a strong formal aesthetic. www.jjlevine.com

Dayna McLeod is a freelance writer who has written extensively on art and art practices. She is also a video and performance artist whose work has shown internationally, and she created and manages 52 Pick-Up (www.52pickupvideos.com), a video Web site where participants make one video a week for an entire year.