Object Relations

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

April 28 to July 31, 2016

Par Jill Glessing

A desire to produce and circulate images drove the invention of photography. Almost two centuries later, the dream verges on nightmare as archivists and image theorists scramble to find space and meaning for all the photographs that have been produced. It’s a good time for collectors. One of them – German artist Thomas Ruff – has, for nearly three decades now, been exploring the properties and potential of images made by others. The Art Gallery of Ontario exhibition Object Relations1 emphasizes Ruff’s role as artist-collector-curator.

Ruff’s appropriation and repurposing of photographs joins a tradition that developed alongside new technologies that facilitated the proliferation of mass-media images. Many engaging in the form – John Heartfield in the 1930s, the Situationists in the 1960s, and Barbara Kruger in the 1980s – sucked the potency out of found imagery to make hard political critiques. Others, less polemically, used it self-reflexively to explore the nature and history of the photographic medium. Ruff is among these. An eclectic mix of archival and reworked images – none originating in his own camera – engage with diverse media and genres across photographic history: science, photojournalism, industrial photography, and art – all now processed into “art.” Drawn from a much larger oeuvre that also explores pornography, landscape, architectural works, and portraits, the selection in this show exhibits the artist’s breadth and openness to diverse inspirations.

Ruff gained art-world recognition in 1986 for his large-scale, museum-friendly colour portraits of his Düsseldorf peers (Porträts). The work’s straight, typological approach makes clear that Ruff took the instruction of his teachers, Bernd and Hilla Becher, deeply to heart. But beneath the portraits’ realism lies the perverse tendency of resistance to authority: the evenly lit faces offer up every surface detail, yet their blank expressions bar any deeper access. The series was made in the wake of the “German Autumn,” when officials, roused by the Baader-Meinhof Group, were slipping toward a surveillance state and demanding photo ID at every turn. Beneath what might seem to be a student’s adoption of his professors’ straight style were critiques of both the aesthetic convention of realist transparency and, in showing all but telling nothing, the state panopticon. These contradictory currents persist through Ruff’s oeuvre: his documentary images line up behind the German Neue Sachlichkeit tradition, but his polymorphous play promiscuously challenges hierarchies of genre, media, and historical process and undermines the possibility of photographic “truth.”

Anchoring the centrality of archival materials for Ruff are pieces from his collection, including Étienne Léopold Trouvelot’s 1885 albumen print of an electrical charge and two stunning photograms made by Arthur Siegel in the 1940s. Examples of Ruff’s own 3-D digital photograms, inspired by Siegel’s, would have lent illustrative symmetry, but were surprisingly absent.

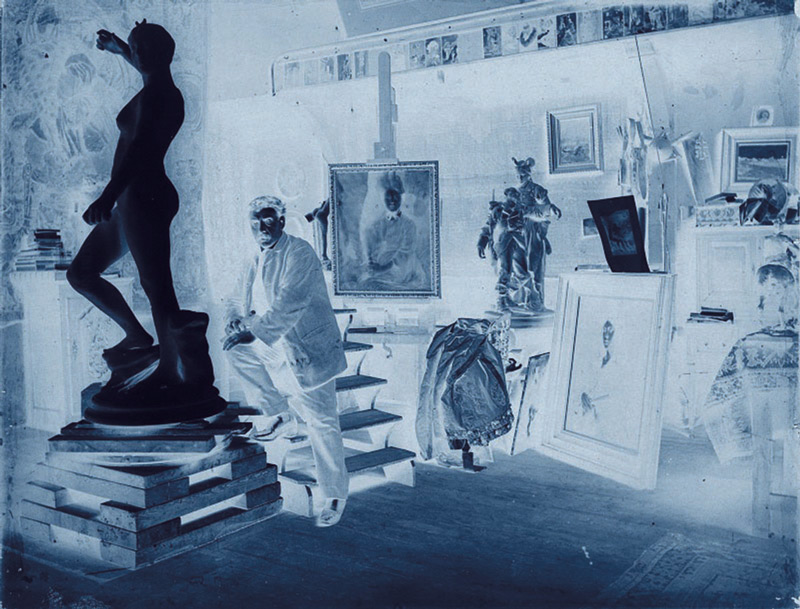

Most conceptually intriguing were digitally produced negatives based on historical photographs from Ruff’s series negative (2014–16): one group based on Étienne-Jules Marey’s chronophotographs, from the AGO vaults, and another on late-nineteenth-century prints of artists in their studios, from Ruff’s collection. Accentuating Ruff’s wanton disregard for purity of process and genre (by intertwining science, photography, and art) are their smaller size – diverging from large-format presentation, almost standard now for contemporary photographic art, a phenomenon that Ruff himself helped establish – and their blue tones that suggest the historical cyanotype process. Inspiring these works, Ruff explained during an exhibition tour, was his daughter’s unfamiliarity with what had been the master of almost all photographs since 1835 – the negative. Ruff asks us to reconsider this primal technology, either in nostalgic tribute or, for the first time, as a unique aesthetic object in its own right.

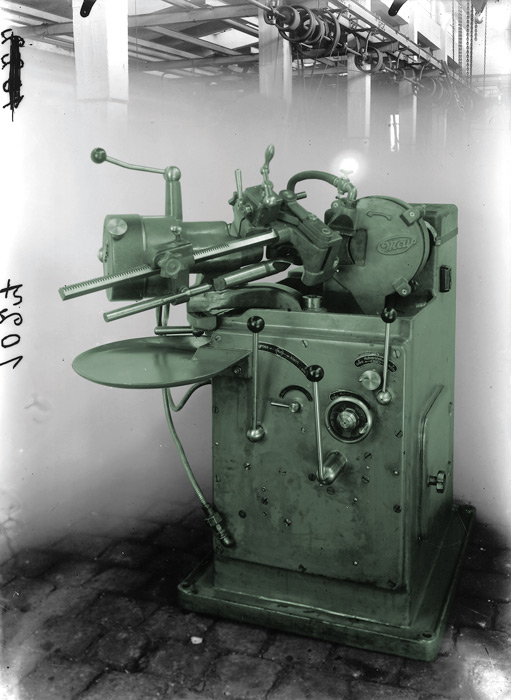

In addition to antiquated image technologies, Maschinen (2003) explores outmoded industrial processes. Ruff’s collection of historical glass-plate negatives of factory equipment had been made for reproduction in advertising catalogues. The machines, too large to move to studios to be photographed, were instead isolated from their factory environments by sheets of white fabric that was then airbrushed to a gauzy, ghostly haze. Further delineated by Ruff with colour, the lowly behemoths – appearing as strange beasts from an earlier time or alien monsters – are here made grand through their large-format presentation. Clearly resonant with the Bechers’ typologies of obsolete industrial infrastructure, their influence is undercut by Ruff’s playful obstruction of authenticity.

The four images from Ruff’s latest series, Press++ (2015), based on archival press images made originally for news media, entered the artist’s collection via eBay. Once published on disposable newsprint, they are here transformed into monumental displays, both by their massive enlargement and by the choice of subject – masculine conquests, both military and astronomical, showing soldiers in battle, astronauts landing, and the equipment they play with. The once-discrete fronts and backs of the photographs are conjoined, making a dense image-text palimpsest of signs: the original photograph, the coloured lines marking out the edited version, and a nest of textual information – labels, catalogue numbers, and directions for use.

A more diminutive collection of rephotographed newspaper images is encased in a long vitrine in the centre of a third gallery (Zeitungsfotos, 1991). Ruff had clipped the originals from newspapers earlier; revisiting them years later, he found that, bereft of their contexts, they were incomprehensible.

The exhibition is beautifully installed overall, but the final room slips into the realm of stunning. It is, no doubt, the four elegant, vertical frames holding deep black skies sparkling with celestial bodies that brings it there. Sterne (1989) was the work that first led Ruff into territories of appropriation.

With a keen interest in astronomy, but acknowledging his inability to photograph it properly, Ruff purchased telescopic negatives from the European Southern Observatory in Chile, which he digitally edited. Unlike Ruff’s other series – for example, Nudes (2012) and jpegs (2004–07), which were obviously distorted through pixilation or softening – the manipulation here is imperceptible, thereby advancing his work deeper into the slippery terrain of appropriation.

Ruff’s Object Relations offers an intricate and beautiful foray through the history of photographic image making, asking us to consider existential questions about the presentation, mobility, and meaning of this frighteningly omnipresent medium.

Jill Glessing teaches at Ryerson University and writes on visual arts and culture.