[Spring-Summer 2017]

By Colette Tougas

From July 19, 2016, to February 19, 2017, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts mounted an exhibition titled She Photographs, described in the press release as a “feminine echo” of the Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective at the museum in autumn 2016. More than simply an echo, this presentation of works by thirty female photographers, most of them Canadian, painted a strong and true portrait of more than a generation of artists (born between 1936 and 1982) in terms of subjects, concerns, and styles. Organized by Diane Charbonneau, curator of modern and contemporary decorative arts and photography at the MMFA, the selection of some seventy images was divided into sections that conferred coherence on the exhibition as a whole. I freely identified these sections as landscape, still life, environment, portrait, self-portrait, self-fiction, performance, documentary, seriality, daily life, identity, and the sublime.

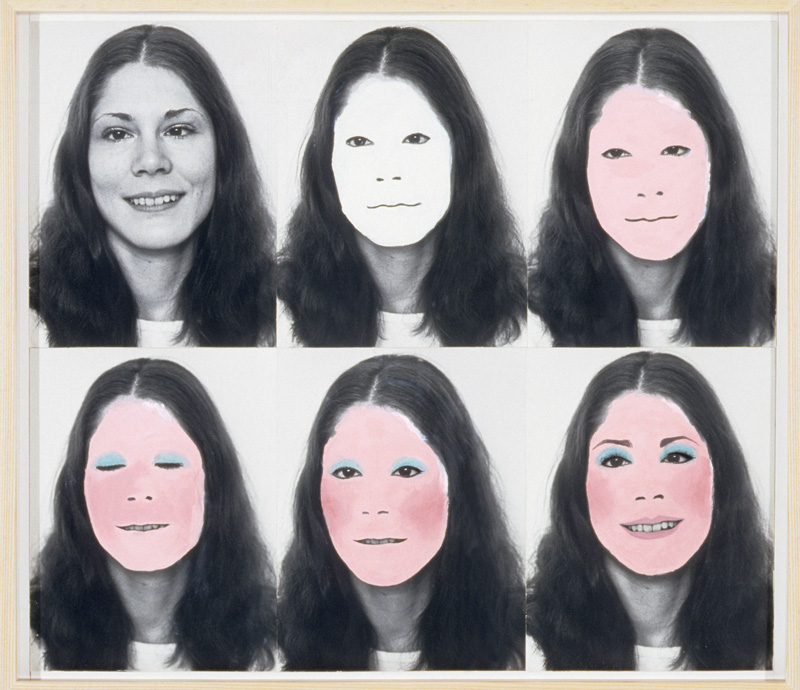

The oldest work in the show was Suzy Lake’s A Genuine Simulation of… no. 2 (1974); this piece offers a good example of performance-related art of the early 1970s, in which the artwork was based on a simple, repetitive approach – the reiteration of a motif, a gesture, an idea. Here, the point of departure is a “plain” black-and-white self-portrait, which is reprinted and “made up” in five ways to create five completely different expressions. Lake’s self-portraits were installed alongside an untitled self-portrait by Kiki Smith (1996), in which the artist appears with her torso nude and her face covered with what looks a clay mask that is similar to Lake’s second portrait – which refers to the neutral mime’s mask. On the same wall was a work by Janeita Eyre, Red Like Meat (2002), a double self-portrait that is disturbing both for its carnival-like makeup and for the subject evoked: a link between meat and human flesh. Also in this section were Shari Hatt’s nine headless self-portraits, Breast Wishes (1996), which gradually reveal, in a performative and serial deployment similar to Lake’s, the result of breast surgery. The subtext shared by these works is the notion of feminine identity, questioned visually through the mask and self-transformation, through criteria both personal and societal.

Nearby, a large diptych by Geneviève Cadieux, Ruby (1993), juxtaposes an enlargement of bright-red cancer cells and a tight framing of a woman’s nude back and grey hair. Aside from the confrontation between abstract-looking and figurative images, between a potentially devastating visual beauty and the body of a subject who may be suffering from the disease, the link created by the parallel placement of the two pictures encourages a reflection on the illusion and precariousness of beauty. This work opened the way to an entire wall devoted to documentary-type photographs; in turn, Julie Moos, Claire Beaugrand-Champagne, Clara Gutsche, Sarah Anne Johnston, Lorraine Gilbert, Catherine Opie, and Katy Grannan put us into contact with women, men, young people – tree planters, athletes, apprentice, contractor, soldiers, tattooed man and woman, red-haired girl – who represent “ordinary” people in their daily life. These works, dated from 1987 to 2012, continue the documentary tradition of depicting ordinary people, the middle class, even marginalized people, to give them a voice and crystallize their existence.

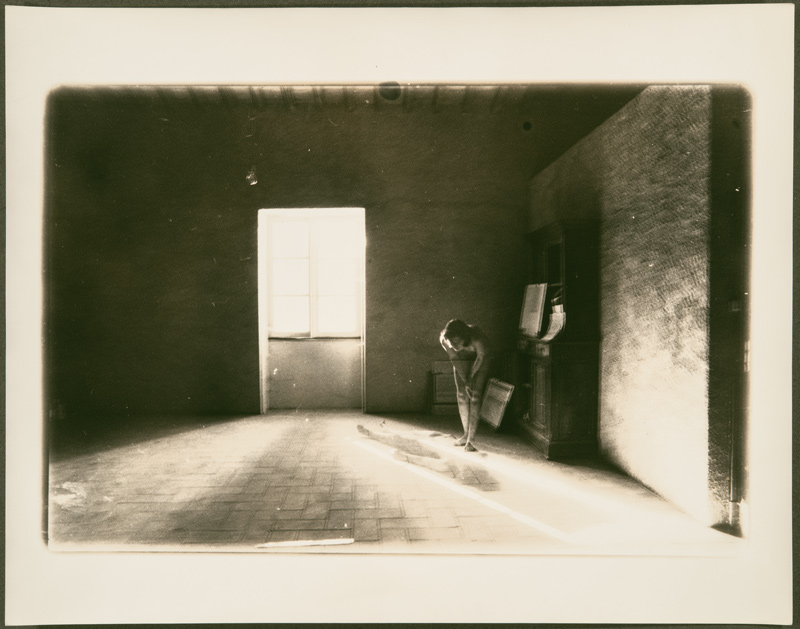

Also in an personal mood and hung on recessed walls, four black-and-white images by Éliane Excoffier were displayed alongside Alix Cléo Roubaud’s series Si quelque chose noir (1980). Excoffier’s first photograph, a female nude titled Obscures II (2004), was accompanied by three images from the series Kiev (2008), the title of which is taken from the Soviet-era camera used to take them. The camera itself is the object of the first photograph of the series, which is flanked by two female nudes, one taken from the front and the other from the back. On the other wall was Roubaud’s series, consisting of seven prints, the first one of which is text only. The other six images show a room that is empty, aside from a piece of furniture against a wall and a beam of light across the floor, in which appears the body of a nude woman, sometimes doubled, sometimes in multiples – all of them ghosts haunting this deserted space. Both artists have exploited and manipulated black-and-white photographic images, either to create an antiquated eroticism, close to the sublime, or to speak of both disappearance and persistence.

Another section of the exhibition focused on a different aspect of daily life, articulated around intimacy, couples, coupling. Interrupted conjugal dialogue (Cadieux); couple in the middle of lovemaking (Andrea Szilasi), after lovemaking (Nan Goldin), and (perhaps) before lovemaking (Justine Kurland); anxious female soliloquy (Raymonde April); men and/or women (Alix Cléo Roubaud), and bedrooms during travel (Gutsche) were the subjects. Out of all of these works, dating from 1980 to 2003, emanates a strange state of stillness, a close examination of communication and the incommunicable, merging and separating, exchange and anxiety, before and after. In the 1980s, these subjects (which still have currency) were favoured by women artists inspired by feminist struggles and feminists’ denunciation of the patriarchy and machismo.

In another grouping, the two youngest artists in the exhibition were brought together both physically and through their interest in the interaction between humans and their environment. #4 Brise glace (2016), a black-and-white photograph by Jacynthe Carrier, shows a figure pushing on a boulder or a block of ice, an action that seems to refer to the myth of Sisyphus. Beside this work, two photographs, also black and white, by Maryse Goudreau, from the series Manifestation pour une mémoire des quais (2011), stand out for their old-fashioned look resulting from the artist’s use of a nineteenth-century camera and process that give her images a feeling of temporal precariousness that matches the subject addressed: the loss of open points of view of nature. On an angle with the preceding wall, Barbara Steinman was represented with a study for the installation Day and Night (1989); this serial work is composed of four images showing what appears to be a barefoot, homeless man in different positions, apparently trying to sleep. Beside this work was Sorel Cohen’s The Shape of a Gesture (1977), a photomontage of seven self-portraits of the artist waving a piece of yellow fabric – thus literally illustrating the title of the work. The works by Steinman and Cohen, although distanced in time, are deployed in a similar mode, that of performance and series, but they differ in their tone: the former portrays a social concern, whereas the latter bespeaks essentially formal research.

A second series by Cohen was hung a little farther on. Titled The Wounds of Experience (1995–96), this work is composed of nine prints with subtitles. For each of them, the artist photographed a psychoanalyst’s office with couch, pillow, armchair, carpet, and sometimes exotic objects. Under each image appear keywords – “Loneliness,” “Psychic Suffering,” “Infantile Trauma,” and “Sexual Inhibition,” for example. Here, too, there is the sense of a certain form of action, or performance, that described by the statement, despite the absence of the real bodies of the patient and the psychiatrist. Even though we know that great suffering is expressed in these offices, they nevertheless give off a reassuring, peaceful ambience, even including culturally stimulating symbols.

Nearby, we were confronted with the material remains of life in two works by Spring Hurlbut, taken from the series Deuil (2005). In Scarlett #1, a ruler is positioned under twenty small bones arranged by size; in Scarlett #2, the needle of a scale, on which is placed a bag of ashes labelled “1994 – Vancouver Crematoria 262,” indicates a weight of about thirty grams. This is what remains of a human body after incineration: a few small bones and dust. On the other hand, on the neighbouring wall, four portraits from the series Personnes âgées, produced by Claire Beaugrand-Champagne between 1973 and 1978, offered a sensitive and touching vision of old age, highlighting the diverse daily lives of elderly people and the testimonial value of their experience. Cadieux’s photograph Sans titre (Main) (1997) closed the section; this black-and-white image of a middleaged woman’s bare forearm could also be seen as a landscape or a still life.

Farther on, five works actually represented the still-life genre. Two photographs by Laura Letinsky, taken from the series I did not remember I had forgotten (2003), fit within the pictorial tradition of depiction of foods, flowers, and vegetables, except in this case the subject is table scraps – a subtle commentary on consumer society. Nearby were Carol Marino’s 1981 photographs Homegrown Sunflower, No. 1 and Erotic Iris, No. 9, black-and-white still lifes whose lucidity is reminiscent of the inventory of plant forms produced by Karl Blossfeldt in the early twentieth century. Finally, Excoffier’s blackand-white photograph titled Game (2012) shows white feathers twirling on a black background composed of twenty-four rectangles that, with the play on words of its title, evokes as much game birds as a game – more precisely, the surface or game board on which one plays. This grouping speaks to the continuity of the still life and the various issues to which it may lend its form.

The exhibition continued with a section that proposed what could be considered variations on the idea of “landscape.” First was Sylvie Readman’s black-and-white diptych Échappée (1999), with one image showing a winter landscape crossed by a road in the middle of which is a figure, and the other composed of a close-up shot of, or even in, a snow-covered evergreen. The diaphanous light, the pictorial material, and the blurry quality of the work naturally led to the following black-and-white image by Angela Grauerholz, Basel (1986), in which water advancing toward us between two rows of houses has the fluid viscosity of paint. In Refuge (2002–05), Isabelle Hayeur presents a dilapidated passageway between two buildings, with debris in the foreground, toward which a figure in the far back of the image is moving – a contemporary and desolate version of landscape whose title evokes the idea of homelessness. Marnie Weber’s collage of magazine illustrations, Jardin de pierre (2001), offered a counterweight to the preceding image, with its procession of female figures, swans, a Greek temple, and a reproduction of Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss. Holly King’s Forest of Enchantment (1999) is also a constructed landscape, not in the form of collage but resulting from meticulous assemblage by the artist, whose approach tends toward the sublime, the fantastic, and the illusory.

Finally, on two isolated walls were two photographs by Grauerholz, each being a variation on a theme and a material favoured by the artist: light. In the older one, Mozart Room (1993), an empty room is bathed in light pouring in through a huge window and reflected in a mirror, all in sepia tones. From the image emanates an almost metaphysical presence – Mozart’s, one might surmise. In the second work, Light Well (2014), it is the geometric structure of a staircase and the baroque print of the carpeting that dominate as much as the source of the light in the “well”; indeed, as if by inversion, the light strangely emanates from the lower floors and not from the ceiling, as we might expect. And so, what is this mysterious light source that literally inhabits the staircase and its banister, giving them shape? Could it be the spirit of photography?

As someone who has been observing the contemporary-art scene since the 1970s, I had a pleasant sense of revisiting the past at She Photographs, as memories were roused by the rediscovery of certain artists and their works, assisted by the intelligent and sensitive groupings and the subtle nods, which brought back memories of many vernissages and discussions. In this sense, this exhibition is a true retrospective of photographic approaches that have marked, and continue to mark, the Montreal scene and others and which have opened the way to issues and techniques marking the conditions of current practice. Considering that most of the works came from the MMFA’s collection, the exhibition deserved praise. Translated by Käthe Roth

Colette Tougas works in various capacities in the contemporary-art field. She is the author of essays on art and of works of fiction.