[Spring-Summer 2017]

An interview by Carol Payne

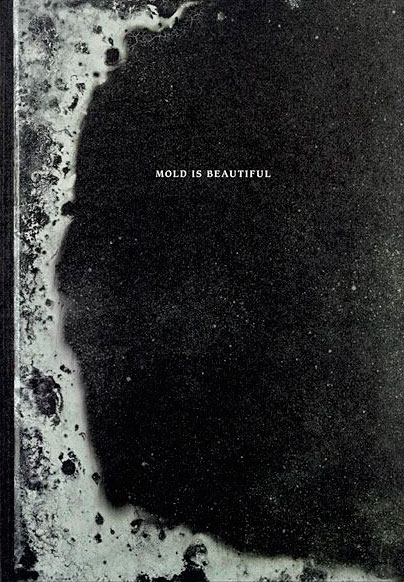

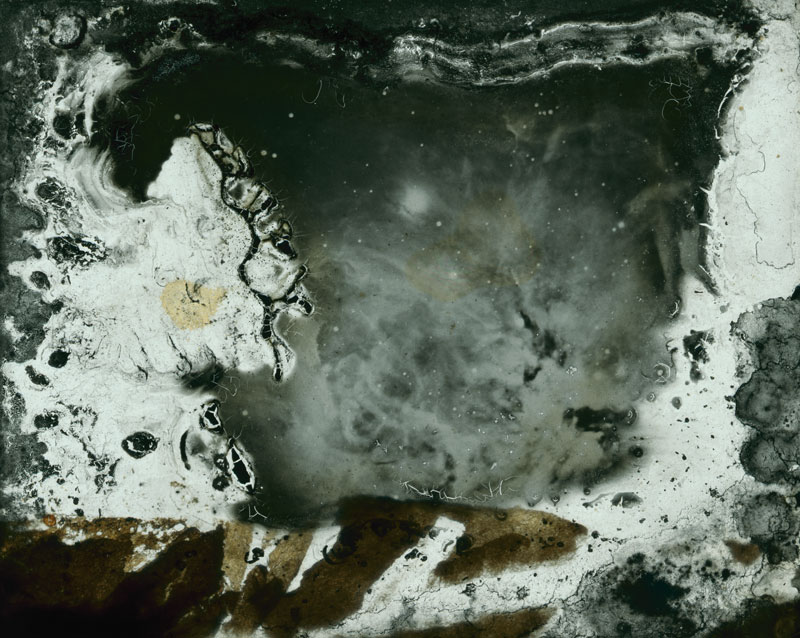

In late 2016, Luce Lebart was appointed the first director of the Canadian Photography Institute at the National Gallery of Canada. For the previous five years, she had been director of collections and curator at the Société Française de Photographie (SFP) in Paris, one of the oldest and most esteemed institutions devoted to photography in the world. At the SFP, and at other institutions, she has introduced innovative scholarship and exhibition practices, including bringing to light archival photographs and photographic objects and linking historical collections with issues in art and society today. As a historian of photography, Lebart is particularly interested in documentary and scientific photography and in photographic techniques and processes and their connections with contemporary art practices. Among her most recent publications are Lady Liberty (Éditions du Seuil, 2016) and Les Silences d’Atget (Éditions Textuel, 2016). She has organized exhibitions and published books on the work of Hippolyte Bayard (Tâches et Traces), on First World War photographer Léon Gimpel, on forensic photography (Crime Scenes), on historical photographs of Egypt (Souvenir du Sphinx), and on Brazilian photography from the 1950s and 1960s. In addition to her scholarly, curatorial, and archival work, Lebart loves to produce photobooks. Her most recent photobook, Mold is Beautiful, was published in 2015 by Poursuite editions in France.

In 2015, the National Gallery of Canada (NGC) announced the establishment of the Canadian Photography Institute (CPI)/Institut canadien de la photographie (ICP) in conjunction with David Thomson, a photography collector and chair of the Thomson Reuters Corporation, and Scotiabank. The CPI will encompass the NGC’s legacy collection (established in 1967 by then-curator James Borcoman), the holdings of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, and donations from the Globe and Mail photographic archive and the Archive of Modern Conflict, a collection of vernacular photographs held by Thomson. The CPI describes its mandate as developing “an accessible collection, active program, research hub, and digital portal for academic and public engagement.”

CP: Can you tell us a bit about your accomplishments as director of collections at the Société française de photographie?

LL: I went to the SFP to take charge of the collection and manage the agency. My first success was to draw attention to the extraordinary wealth of the collection by inviting artists to create new works using the existing images for inspiration. At the time, I took as a model the pioneering approach of the Archive of Modern Conflict in London, whose publications reflected symbiotic relationships between the collection and artists. I was also able to obtain grants that made it possible to initiate the first mass digitization projects at the SFP; among other things, we digitized six thousand autochromes by artists in the collection. Digitizing the SFP’s very diverse collections was a thorny challenge, as the supports for the images ranged widely: Niépce’s heliographs, for example, had been made on tin plates; Daguerre’s daguerreotypes were on copper; the autochromes by the Lumière brothers included potato starch . . . It was extremely stimulating work, and the mechanisms and protocols for taking the shots were different each time. Ten images, however, resisted reproduction; they were heliochromes by Niépce de Saint-Victor, which had been stored since the nineteenth century in a sealed box bearing a label that said, “Do not open, disappears in light.” No light, no photograph – even digital. Nevertheless, we managed to digitize Hippolyte Bayard’s book of tests, made in 1839, even though the images, barely visible and not fixed, were very sensitive to light.

My greatest honour was certainly, just after I started in the position, to be asked by François Hébel, the director of Les Rencontres, and Rémy Fenzy, the director of the École nationale de photographie (where I had studied twenty years before), to organize a major exhibition during the Festival international de photographie d’Arles, and then to organize four more over the last five years. The SFP is a scholarly nonprofit organization with no space or budget for exhibitions, so if we wanted to do things, we had to invent them – find contacts, partners, publishers, and funding. I worked with incredible people from a wide variety of backgrounds, all connected by the same intense passion for photography.

My first exhibition at Arles, in fact, was titled The SFP collections. A laboratory for first time experiments, a project that I’d like to reprise. With the help of contributors and young volunteers, we opened the SFP’s boxes one by one, completed inventories, and digitized the pieces at the same time as we were preparing the exhibition. We were very lucky to be able to take advantage of the inventorying process to bring images out of the reserves and share them with a variety of publics!

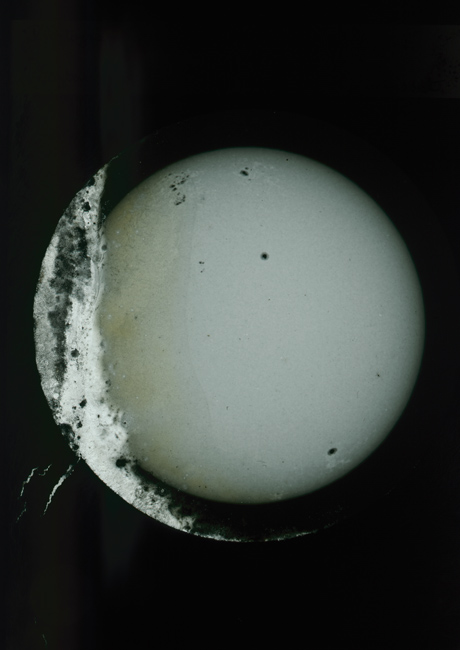

This exhibition became a sort of laboratory on photographic innovation. It enabled me to bring iconic images, such as Daguerre’s first daguerreotype, out of the shadows. It also afforded an opportunity to show old photographs not as yellowed images, antiques, but from the angle of their modernity. I am still completely fascinated by the immense creativity and innovativeness of the pioneers of the fixed image and by all of the formal, aesthetic, scientific, and technical inventions by early photographers. Through a succession of innovations, photography truly began to offer multiple and extremely changeable images. I was surprised to learn, for example, that Léon Foucault was only twenty-five years old when he produced the first microscopic daguerreotypes, in 1844! The same year, he also produced a daguerreotype of the solar spectrum that is exceptionally sublime: an image of light itself, on metal, with Barnett Newman– like bars, almost abstract. At the time, photography was in the full bloom of youth: every experiment was possible, and on every support! In the nineteenth century, photography was not in black and white – those tonalities were ushered in with the instantaneous processes using gelatin silver bromide – but could be in any colour, with pigmentary processes allowing for any attempt, every utopia . . .

The exhibition also displayed the first 3D images, made in Algeria by Ducos du Hauron in the early 1890s. I was happy that this find enabled me to offer a sort of archaeology of the digital. I love these connections. For us, 3D is linked to an American imaginary: 3D films, special effects. So it’s fascinating to discover – by wearing glasses that are more or less the same as those used today – that the earliest 3D images were of Berber women, mosques, rooftops, and the Casbah. And in this exhibition we also presented the first remotely transmitted images (transmitted by radio waves), dating from 1907, including pictures of the Pope. Of course, the Catholic Church always closely monitored all issues related to data communication and transmission.

It was just as exciting to discover the people behind these inventions and how they helped – or didn’t – to build their future. The first albumen photograph on glass was made by Niépce de Saint-Victor, Niépce’s cousin. He signed his name, in enormous letters, on the frame of the image. Sometimes on the backs of images, and sometimes in sealed envelopes, were notes on patents. In fact, all of these innovations had major industrial and financial implications based on obtaining and applying such patents. And that’s not to mention that these inventions were part of history, leaving a legacy to posterity.

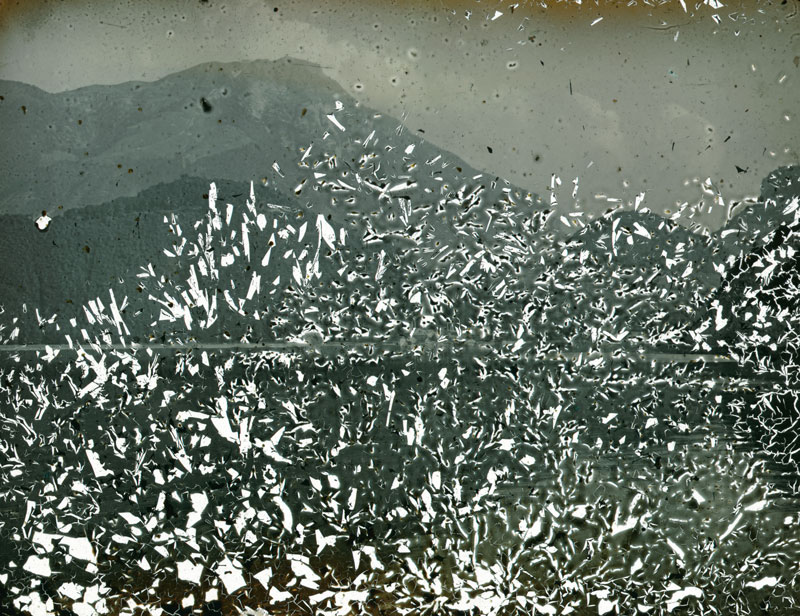

We also found documents relating to a very interesting case from the point of view of reception of such innovations. A German applicant, a certain Mr. Bertchold, had submitted a project to a competition, funded by the Duc de Luynes and judged by the SFP, aiming to encourage research on the development of permanent photography processes. Bertchold’s entry was rejected on the basis of summary arguments. Thirty years later, it turned out that he had invented a screen system, a sort of pre-offset, that had become fundamental for photomechanical printing and all nineteenth-century printing processes. On display in the exhibition were images that had been “rejected” or, rather, had “gone unnoticed,” alongside the reasons for their rejection. Finally, the exhibition provided an opportunity to highlight the beauty of the tests and the aesthetic of trials and errors.

CP: You have written a great deal about the history of photography. How would you characterize your general approach to historical studies of photography? And your interest in interdisciplinarity in relation to the history of photography?

LL: I would say that my interest in a transversal and interdisciplinary approach to photography and its history is related to the fact that I am very engaged with connections among things, people, communities, and bodies of knowledge, but also with change, with things that move and make us question ourselves.

I’ve always been fascinated by family pictures, but also by anonymous photographs and by scientific and documentary images – all of those images that were produced primarily with no artistic intentions and yet have aesthetic qualities. I always keep in mind how malleable photography is, how easily it has changed status over the years depending on who is looking at it, and how vernacular practices as much as artists’ practices have modelled our vision and imaginations. I will say that the question of imaginations is central to my approach to images. Bringing together and organizing an anthology of essays on Atget was an amazing experience in this respect. After Atget’s death, all of these authors collectively contributed to making and finally forging his authorship. This question of authorship has been woven throughout the history of this photographer’s reception. Was he an artisan or an artist – or both? A producer or an author – or both? The contributors to this anthology discuss at length the permeability of these notions. In fact, photography questions art and also challenges the very notion of the artist. It takes no account of categories and forces us to revise them, to think differently.

CP: How do you plan to transpose this experience and knowledge into your new mandate? What are your main challenges and objectives as director of the CPI?

LL: One of the most important objectives of the CPI is to share its images and collections with as broad a public as possible, while maintaining an intense relationship with Canadian and international photographic communities.

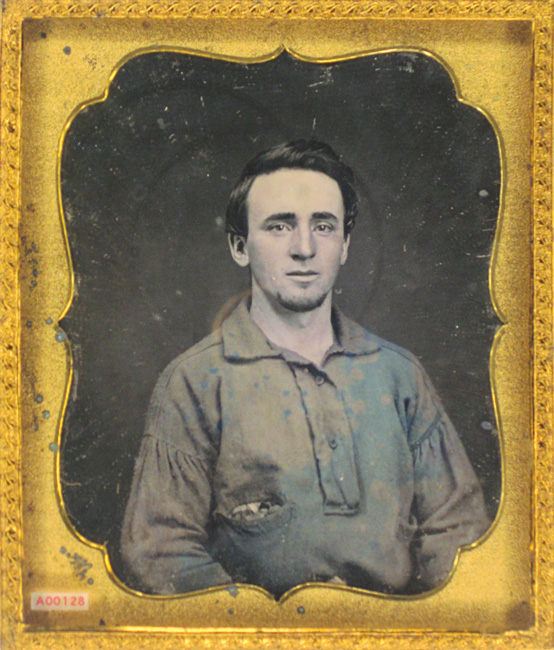

Such sharing takes place, of course, through exhibitions and publications, but also by digitizing documents and putting them online. Currently, the CPI is well positioned to meet these long-term challenges, as its creation was supported by major financial contributions from Scotiabank. The CPI also benefited from the contribution by the founder of the Archive of Modern Conflict, who has already offered unbelievable donations such as the well-known Origins of Photography collection, which we are currently in the process of digitizing.

It seems essential to me that we work with young people. Ottawa is a university city and, and so there is an interesting pool of researchers. But it is also important that many other people “encounter” our collections. To this end, we offer research grants and regularly organize visits behind the scenes, as well as numerous educational activities and activities for families and school groups. The CPI wants to encourage young historians and exhibition curators, and to invite artists to work with the collections. In this perspective, we have inaugurated the PhotoLab, a small space for more experimental exhibitions and staunchly collaborative approaches involving students and partners from different communities of photography research in the country, as well as independent associations. The idea is to involve and integrate contributions from all kinds of sources and, in a way, to bring gazes together.

The fundamental idea is to contribute to the development of an image culture. More than writing, the reading of images is also something that is learned!

CP: Does the CPI aim to become an increasingly international organization, with collaborations abroad – especially in Europe?

LL: The CPI will continue to circulate its exhibitions in Canada and abroad, but we are definitely encouraging collaborations. Whether they are exhibitions, conferences, or books, we want to work with others, share our collections and ideas, and come up with new joint projects.

I am particularly interested in developing projects beyond the CPI’s walls. For the upcoming edition of the Contact Festival in Toronto, next month, we are mounting an exhibition in the St. Patrick subway station in Toronto titled Canada in Kodachrome. We won’t stop at Canada’s borders, as we’ll be developing projects with various countries. We want to open up to all continents. However, our expertise is, of course, Canadian photography and its history. We have just inaugurated the CPI’s third major exhibition, with curator Andrea Kunard: a mosaic of 120 works from the collection recounting forty years of photography in Canada.

Translated by Käthe Roth

Our thanks to Marie-Maxime De Andrade for transcribing the French version of this interview.

Carol Payne, a historian of photography, is an associate professor of art history at Carleton University. She is the author of The Official Picture: The National Film Board of Canada’s Still Photography Division and the Image of Canada, 1941-1971 (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2013) and co-editor, with Andrea Kunard, of TheCultural Work of Photography in Canada (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2011). https://carleton.ca/arthistory/people/payne-carol/