[Winter 2020]

Par Erika Nimis

Dakar, a cosmopolitan capital city and crossroads on the Atlantic coast, open to all creative currents, has grown under the gaze of its photographers. An independent field of professional photography emerged in the 1990s, and the institution of the Mois de la Photo has contributed to legitimizing an increasingly engaged scene turned to creativity1 and permeable to international influences. In this essay on the photography scene in Dakar, I build on key moments that have marked its history since the nineteenth century.2

The Precursors. As it did in other West African coastal countries, commercial photography developed in Senegal in the late nineteenth century,3 in a colonial context, and was appropriated locally in the 1910s and 1920s. Recognized as the forerunner of Senegalese photography, Meïssa Gaye (1892–1993), having travelled around the country as an agent of the colonial administration, opened his own studio in 1945 in Saint-Louis, the capital of Senegal until 1957.

Considered the cradle of Senegalese photography, Saint-Louis (Ndar, in the national Senegalese language, Wolof) has continued to host the richest Senegalese photography collections, both private and institutional, of the first half of the twentieth century, some of which are accessible at the Centre de Recherches et de Documentation du Sénégal (CRDS) and at the Musée de la Photographie (MuPho), recently founded by collector, businessman, and patron of the arts Amadou Diaw. One of the most extensive collections in the country is that of Adama Sylla, a former curator at the CRDS museum and himself a photographer.4

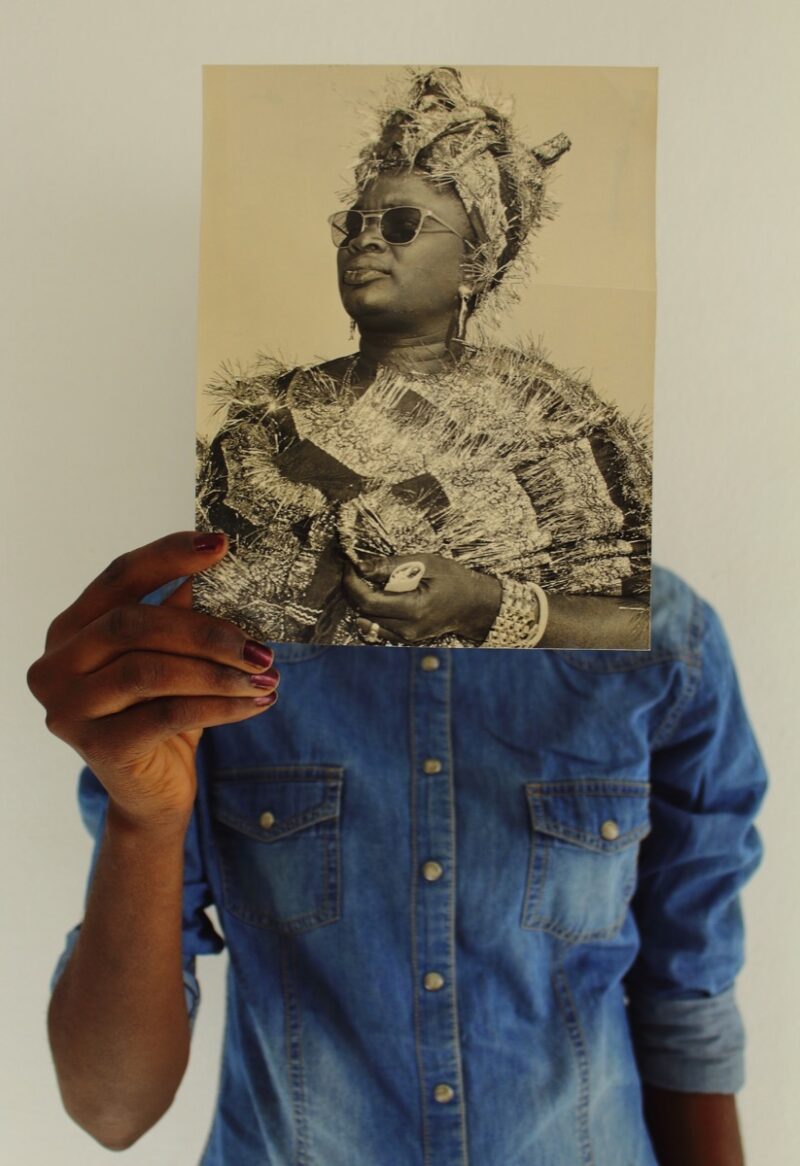

Let’s return to Dakar, today’s capital, where Médina, the African district of the city during the colonial period, today the “muse city” of artists (to use the [translation of the] title of a 2016 exhibition), was home to the city’s early Senegalese and African photographers. In 1943, Mama Casset (1908–92) opened his studio, African Photo, at the corner of Rue 35 and Avenue Blaise Diagne in Médina.5 As a child, Ibrahima Thiam (b. 1976) rummaged through the photography collection of his grandmother, a fabric dyer in Saint-Louis, and admired the pictures taken by Meïssa Gaye, Mama Casset, and many others. Now himself a photographer and collector, over the last few years he has developed a series, Portrait Vintage, through which he uses a simple and highly effective procedure to, as he put it, “reconstruct the collective memory, rethink photography old and contemporary, and make it a site of dialogue.”6

Similarly, Malick Welli (b. 1990), in his series Duet, which resulted from an artist residency in Saint-Louis, revisits the history of portrait photography in Senegal. This series was presented in late 2017 in the inaugural exhibition at MuPho, Songes d’hier, Rêveries du présent, alongside previously unpublished portraits of Saint-Louis women taken from the 1930s to the 1950s and works by eight other contemporary photographers, among them Laeila Adjovi, Malika Diagana, and Omar Victor Diop (including Diop’s famous self-portraits inspired by historical paintings that were recently presented at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts7). The “duet” presented here brings together two childhood friends, well known in the city, who pose sitting in front of a wall covered with portraits of the great marabouts of Senegal, but also, if we look closely, some notorious figures of colonial history – in short, a summary of Senegal’s political and religious history.

The 1990s: A Breach Opens. When Senegal gained independence, Léopold Sédar Senghor, the country’s president from 1960 to 1980 and a great lover of the arts, implemented an ambitious cultural policy that included the creation of art schools, museums, and cultural centres. The Festival mondial des arts nègres, organized in 1966, engendered the “Dakar School” art movement embodying Senghorian thinking.8 The Dakar School produced a generation of artists who soon felt constricted by the conception of art advocated by Senghor. In the wake of May 1968,9 some artists joined a protest art movement led by Issa Samba, known as Joe Ouakam (1945–2017), Laboratoire Agit’Art (founded in 1974), and Village des arts (in its early version, dissolved in 1983).10

At the time, photography was still usually viewed as the “humble servant to art,” as Beaudelaire famously put it, even though the young generation was sensing a shift in the wind. In the late 1980s, ten photographers were spending time at a photography club at the Centre culturel français. There, they began to organize, help each other out, and make their mark in the Dakar art scene. In 1990, this photographers’ collective put together the first Mois de la Photo de Dakar, with the support of the Centre culturel français, the local cultural press, filmmakers, visual artists, and Paris-based publisher Revue Noire. The event offered ten exhibitions, debates, screenings of films on photography, and a Young Talent composition – all this at a time when “the development of free media and deflation of national photography agencies [allowed for] the rise of independent professional photographers.”11 Boubacar Touré Mandémory, one of the instigators of the event, concluded, “We were able to make enough of an impression to have photography accepted as belonging to the visual arts in Senegal. A breach had just been opened as a prelude to the Rencontres de Bamako.”12

Mandémory and Bouna Médoune Sèye are two leading figures of the generation that opened that breach. An experienced photojournalist, Mandémory (b. 1956) participated in a number of pioneering projects, including, in the 2000s, the creation of the PanAfrican Press Agency (known as PanaPress). His style is recognized for his unusual camera angles, often at ground level, and his saturated colours; he is also fond of wide-angle and fish-eye lenses. He moved to Guédiawaye, a town outside Dakar, where he, like other early colleagues, trained the young generations, bringing them together in collective projects such as Regards sur la ville de Rufisque (2014–15). For more than twenty years, he has been photographing Guédiawaye, which is threatened by rising seas.

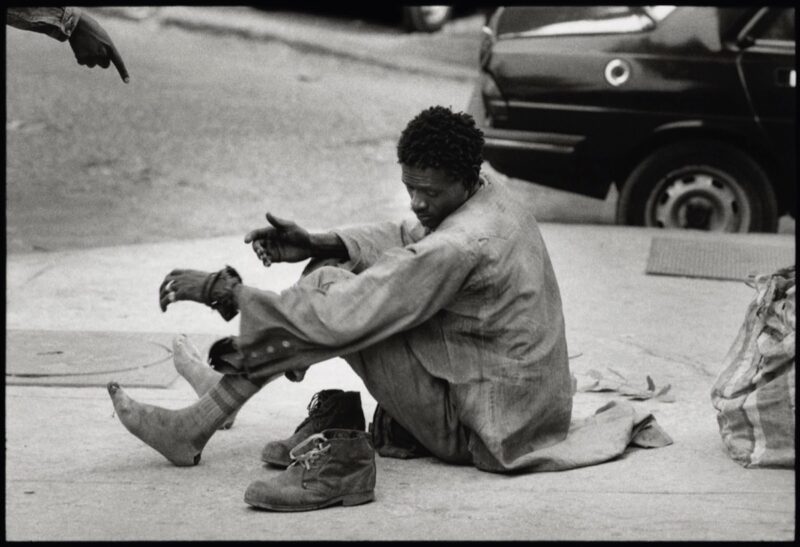

Sèye (1956–2017), a member of Laboratoire Agit’Art, was first interested in photography (trained in France), and then transitioned to moving images and explored other art forms, such as painting and poetry. Freed by the philosophy of the “laborantins,” he paid particular attention to social outcasts and made his name with his series on the “mad people and rejects living on the sidewalks of Dakar.”13 In late summer 1993, he was in artist residency at La Chambre Blanche, in Quebec City.

In the wake of Le Mois de la Photo de Dakar (which had several editions up to 2000), in late 1994, Les Rencontres de Bamako, the first biennale in Africa devoted entirely to photography, was launched. A few photographers from Le Mois de la Photo de Dakar, including Mandémory, Sèye, Djibril Sy, and Moussa M’Baye, also had works exhibited at this event.

Elise Fitte-Duval (b. 1967), a Martinican based in Dakar since 2001, was also on the program for the first edition of Les Rencontres de Bamako, in the Off section organized by Revue Noire.14 She has since been a regular presence at Les Rencontres, as she won the Prix Casa Africa in 2011 and participated again in the Off in 2019. A documentary photographer, she works on social resistance with regard to environmental challenges and political issues. Her latest series, White Elephants, presented recently in Spain, shows the consequences of implementation of the Plan Sénégal Émergent on people in Bargny, outside of Dakar, who live essentially from farming and fishing and are in a precarious position given urban development.

Social and Engaged Photography. Dakar is now “on the map,” so much so that celebrated art critic and exhibition curator Okwui Enwezor (recently deceased) made sure to visit while he was organizing the exhibition Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contem porary African Photography.15 This was how work by photojournalist Mamadou Gomis (b. 1976) came to be exhibited at the International Centre of Photography in New York in 2006. A selection of pages from his portfolio Arrêt sur image, published at the time in a Dakar daily, was presented in a showcase. Five years later, Gomis and Koyo Kouoh, then director of the Raw Material Company centre in Dakar, initiated a magnificent project for a group exhibition and publication (with the support of the German embassy) on the “Senegalese spring,” during which thousands of Senegalese went into the streets to demand the resignation of the country’s president, Abdoulaye Wade, who wanted to amend the constitution so he could run for a third mandate (2011–12). In the end, nineteen photographers spontaneously joined the project, produced in the effervescence and urgency of the moment, a historic turning point for Senegalese democracy.16 Like his older colleagues who wanted to transmit their experience of the profession to new generations, Gomis founded the Fédération africaine sur l’art photographique in Dakar in early 2018 to “bring together artists from here and elsewhere.”

Another pillar for young photographers, whom she welcomed into her space, Waru Studio,17 Fatou Kandé Senghor (b. 1971) studied in France and then returned to Senegal, where she struggled to establish herself as a director and producer in the male-dominated world of photography and film. In 2006, her work was presented in Snap Judgments. Considering herself a “photojournalist of society,”18 she is currently thinking about the difficulty of transmitting cultural values to young people in an all-digital era. She is also preparing a television series on hip-hop in Senegal.19 By night, she has photographed the sleeping city – and the stacks of furnishings intended for use by retailers, on the edge of the Sandaga covered market,20 closed for renovation and perhaps soon to be demolished. And the retailers will find themselves on the city’s sidewalks.

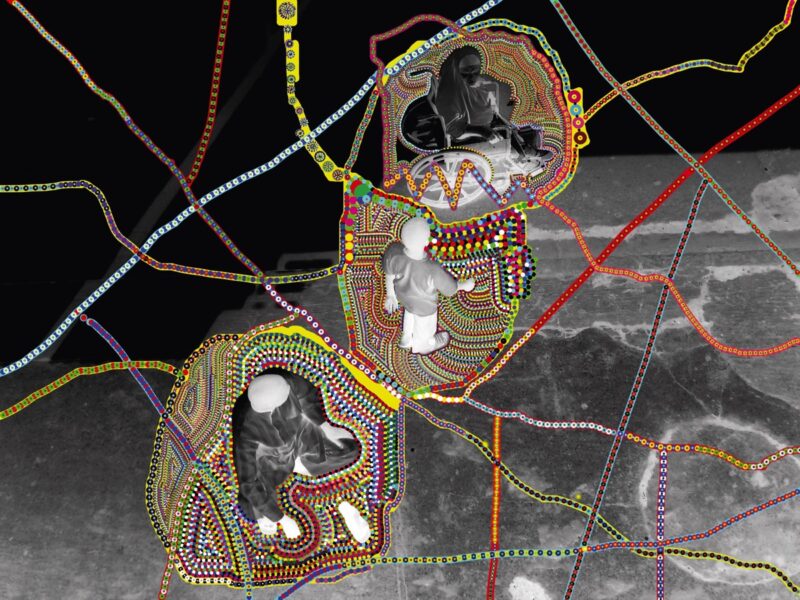

The Sidewalks of Dakar. Photographing the street, the passersby, the merchants, the congestion – in short, daily life in the city – is irresistible for Dakar photographers. Each adopts an approach adapted to the place, the moment, or the subject that reveals an intimate knowledge of and attachment to the city. Babacar Traoré, known as Doli (b. 1984), from Laboratoire Agit’Art, draws his inspiration from life in his neighbourhood, Médina. In a series of photographs taken from his balcony then reworked with graphic tools, he sidesteps the documentary use of photography to explore, with other codes, the “shared urban project” in Médina. In this series, L’homme dans son environnement, the subjects are defined by networks of colour or dots that trace their movements, their energy, and the coloured aura surrounding them. Doli says that he uses this blurring of the subject to respect its image and the codes ruling his society.21

A member of the young generation of versatile photographers, Baba Diedhiou (b. 1991) traded his soccer shoes, following an accident, for a camera and has since been documenting a Senegalese society grappling with social problems amplified by globalization. In 2018, he and visual artist Khéraba Traoré formed a duo called KhéraBaba to combine photography and drawing. They have developed a technique, “typic graphic,” in which they modify photographs with materials as diverse as pastels, charcoal, colour pencils, and press clippings. Parcours du combattant addresses the painful theme of talibé children who walk the streets of Dakar, forced to beg.

This stroll through the streets of Dakar concludes with Mabeye Deme (b. 1979), the only photographer discussed here who is not based in Dakar. That said, he visits several times a year and draws his inspiration from the city, He, too, has found a highly poetic process for capturing life in the neighbourhoods without being noticed. In Wallbeuti. L’envers du décor, he exploits the visual potential of tarps that are hung in the middle of streets during religious and family ceremonies. The fabric of the tarps, with their worn texture and folds, attenuates the colours and softens the realism of the scenes that he captures live, making them timeless, almost hieratic.

Since the breach was opened, in the 1990s, Dakar photographers have forged their path in complete independence, as their international exposure has shown. And that is precisely their strength. Translated by Käthe Roth

[See the printed or digital version of the magazine for the complete article. On sale throughout Canada until June 12, 2020, and online through our boutique.]

2 The idea for this essay comes, in part, from my short yet stimulating experiences in Dakar during two artist residencies (funded by the CALQ) in 2018 (at RAW Material Company) and 2019 (at Village des Arts).

3 Patricia Hickling, “Bonnevide: Photographie des Colonies: Early Studio Photography in Senegal,” Visual Anthropology 27, no. 4 (2014): 339–61.

4 Adama Sylla, “Collectionner, documenter,” interview conducted by Bärbel Küster in Saint-Louis on June 22, 2014, http://dakar-bamako-photo.eu/fr/adama-sylla. html. The website of the “Photographie et Oralité. Dialogues à Bamako, Dakar et ailleurs” project (http://dakar-bamako-photo.eu/fr) gives a closer look at the work of most of the photographers discussed in this essay. Also on that website is an interesting essay by Babacar Mbaye Diop, “Pratiques photographiques contemporaines au Sénégal,” http:// dakar-bamako-photo.eu/fr/babacar-mbaye-diop.html.

5 Mama Casset et les précurseurs de la photographie au Sénégal (Paris: Éditions Revue Noire, collection Soleil, 1994).

6 Email exchange with the author. See also Aïcha Diallo, in conversation with Ibrahima Thiam, “One way to reignite this collective memory,” C&, May 2014, https://www.contemporaryand.com/fr/magazines/one-way-to-reignite-this-collective-memory (our translation).

7 In the exhibition From Africa to America: Facetoface Picasso, Past and Present, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, May 12 to September 16, 2018.

8 Marie-Hélène L’Heureux, “La négritude et l’esthétique de Léopold Sédar Senghor dans les œuvres de l’École de Dakar,” master’s thesis, UQAM, 2009, https://archipel.uqam.ca/2162/1/ M10943.pdf.

9 Omar Gueye, “Mai 1968 au Sénégal,” Socio 10 (2018), http://journals. openedition.org/socio/3144.

10 Elizabeth Harney, In Senghor’s Shadow: Art Politics, and the Avantgarde in Senegal, 1960–1995 (Durham, NC, and London, UK: Duke University Press, 2004).

11 N’Goné Fall, “Boubacar Touré Madémory,” in Contact Zone, exhibition catalogue (Bamako: Musée National du Mali, 2007), 104 (our translation).

12 “Boubacar Touré Mandémory: Militant Photographer and Urban Senegalese Colorist,” The Leica Camera Blog, January 22, 2015, https://www.leica-camera.blog/2015/01/22/boubacartoure-mandemory-militant-photographer-and-urban-senegalese-colorist (our translation). 13 Bouna Médoune Sèye, Trottoirs de Dakar (Paris: éditions Revue Noire, collection Soleil, 1994), back cover (our translation).

14 Érika Nimis, “Rencontres de Bamako – Retour sur la première édition – 1994,” Fotota (blog), January 15, 2019, https://fotota. hypotheses.org/6797.

15 Okwui Enwezor (ed.), Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography (Göttingen: Steidl, 2006). The exhibition toured in North America, including to the National Gallery of Canada, in Ottawa, in late 2007 to early 2008.

16 Koyo Kouoh (ed.), Chronique d’une révolte. Photographies d’une saison de protestation (Dakar and Berlin: Raw Material Company and Haus der Kulturen der Welt, 2012).

17 Founded in 2001, Waru Studio hosts screenings, events, and very lively encounters, such as that for the Fédération africaine sur l’art photographique, in which I participated, in April 2019.

18 Virginie Ehonian, “Fatou Kandé Senghor. En quête d’identité/Fatou Kandé Senghor: A Search for identity,” IAM–Intense Art Magazine, no. 2 (2016): 28–29.

19 Fatou Kandé Senghor, Wala Bok: Une histoire orale du hip hop au Sénégal/An Oral Histor y of Hip Hop in Senegal (Dakar: Amalion Publishing, 2015).

20 “Sénégal: des commerçants opposés au projet du marché Sandaga,” Rfi, September 23, 2019, http://w w w.rfi.fr/afrique/20190923-senegal-projet-marche-sandaga.

21 Portfolio sent by the artist to the author. See also Robin Riskin, “Imagined Realities for the Digital City,” framework5, September 26, 2012, https://framework5.wordpress. com/2012/09/26/imagined-realities-for-the-digital-city/.

Erika Nimis is a photographer, Africa historian, and associate professor in the art history department at the Université du Québec à Montréal. She is the author of three books on the history of photography in West Africa (including one drawn from her doctoral dissertation: Photographes d’Afrique de l’Ouest. L’expérience yoruba [Paris: Karthala, 2005]). She contributes to a number of magazines and founded, with Marian Nur Goni, a blog devoted to photography in Africa: fotota.hypotheses.org/.