[Fall 2022]

Young Men at Risk

By Moyra Davey

Anything you feel you better be able to feel out loud.

– Kathleen Collins, in a workshop for students at Howard University, 1984

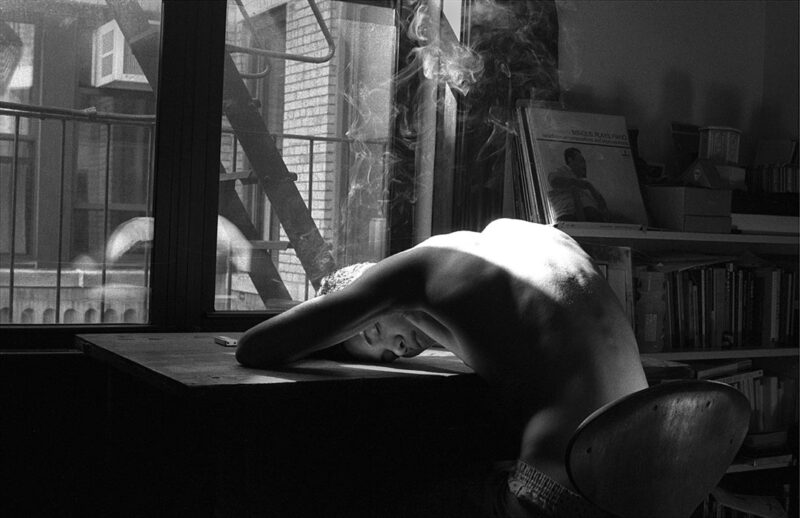

Kathleen Collins went on to say in that workshop, “Good work is dependent on detachment.” It is not obvious how to reconcile the distance between the latter truth and “feel[ing] [things] out loud,” but to my mind Justine Kurland comes very close, consistently operating on a level of de ant self-disclosure and expert mastery of craft. Each new production, especially her proliferation of books and zines, is an upping of the ante, and whether or not she knows and intends it, she is of the rare breed that makes art and “write[s] as if already dead.1”

One of the astonishing things about Justine’s monograph Highway Kind is that its maker “does it all,” parsing multiple canons and combining in one book genres that would normally be found as the province of multiple authors: freight trains, landscapes rural and urban, the road, family, children, animals, the snapshot, the staged, the reprised. All of this is captured “on the y” not with a hand-held 35 mm, but with a cumbersome and painstaking 4×5 camera and tripod.

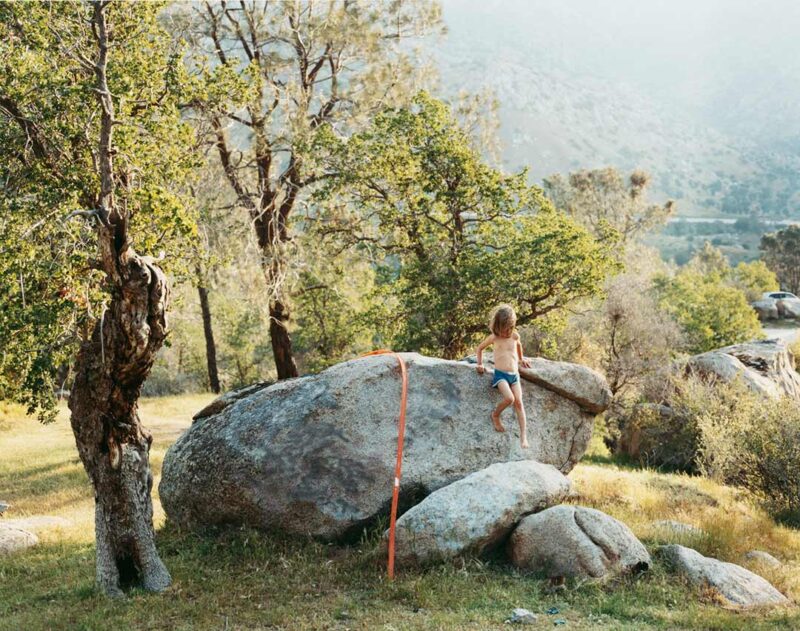

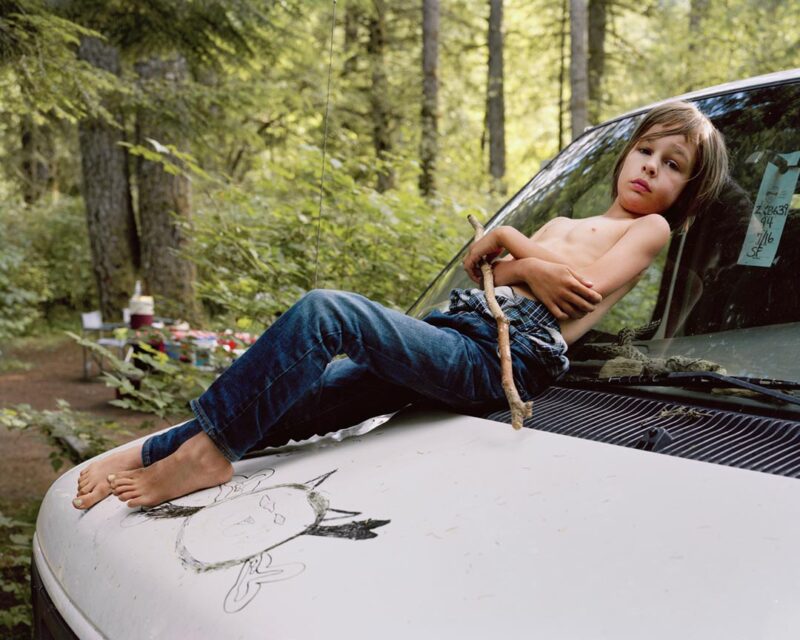

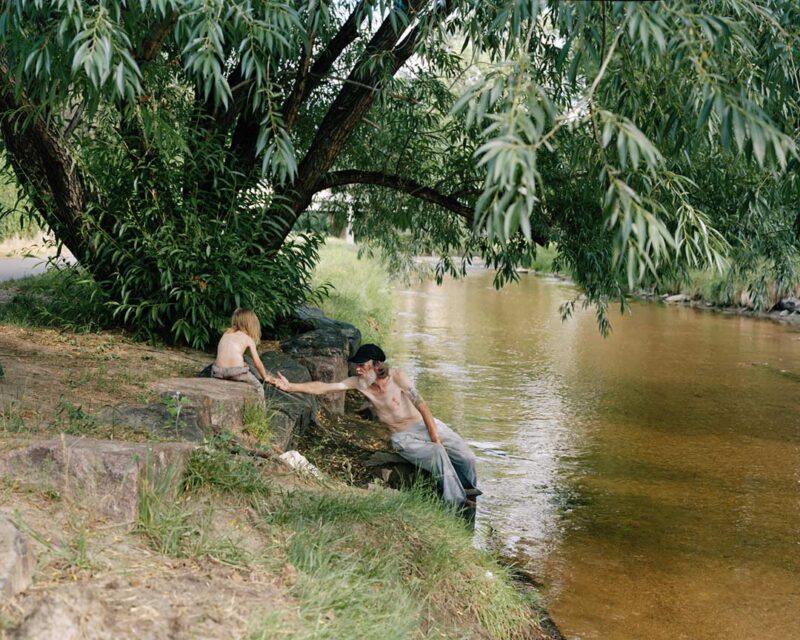

Only fifteen of the eighty-four plates in Highway Kind depict Justine’s young son, Casper, as a baby, a toddler, and finally a lithe young boy holding a pellet gun. Most of the photographs are of fraying, exurban America and its marginalized citizens, or of wide-open landscapes, or of freight trains snaking through desert or forest, toy-like. Yet Justine has penned a gripping narrative coda that focuses largely on Casper and their life together as road-trip companions over a decade, in a van that was both home and studio on wheels. She told me that she could make a PB&J while at the wheel; she loaded 4×5 lm at McDonalds; she carted around bins of Legos and toy trains and made a playroom for Casper at campsites and on riverbeds, and she installed Hot Wheels tracks on a lava bed in California.

I’d known Justine’s work for over fifteen years, but I had never met her until the frigid winter night, sometime around 2006, when she approached me on a street corner in Chinatown, her old pea coat open to the elements, and launched, with barely an introduction but with spirited intensity, into taking issue with something I’d written. I don’t remember what it was, but I’m sure she was right.

“Excepting the occasional rueful aside, my mother made a point not to speak about her children, and like her I’ve been circumspect .”2 What are recent models for a parent writing about a child? I can’t think of too many that are sustained and free of the vanity impulse – Masha Gessen on her son’s addiction to opioids; Maggie Nelson and Harry Dodge, who write about their offspring with humour and detachment and engaging tenderness, giving the feeling that they are dashing off missive with barely time to catch their breath.

As author Nancy Huston has pointed out, fiction and motherhood are often at odds: novels traffic in danger and adventure, while mater seeks to nurture and protect. Auto-fiction or essayistic writing about one’s progeny is a risky business as well, with the joint pitfalls of immodesty and invasion of privacy.

In explaining the function of captions, I believe we are extending our medium.

– Dorothea Lange

The final plate in Highway Kind, just before Justine’s narrative about Casper, is an image of a weathered young man gripping a soda can, in a gesture almost of supplication, and gazing off into the distance. It reminds me of a Jeff Wall setup, it could be staged or not, it doesn’t matter. What is interesting to ponder is the extent to which Justine was in pursuit of the image and her investment in the look of the young man, given the photograph’s extraordinary title, What Casper Might Look Like if He Grew Up to Be a Junkie in Tacoma, and its placement in the book – it is the last of the big, titled plates coming just before Justine’s text, itself interspersed with more casual shots of Casper on the road from babyhood to grown child. It is also the only title in the book that is not strictly descriptive and deadpan.

I’d venture to say that most mothers, even though we might have our doubts, would not, out of superstition, go so far as to spell out this type of speculative destiny for our progeny. But this is an example of Kurland’s audacity, her willingness to speak candidly, both in words, and in images, of things as they are: raw and not glossed over.

We’re very different people. He’s a sneakerhead, a hyperbeast, video games, a car head. I’m learning a lot about shoes. We don’t have any shared interests… we’re so close without being close at all.

– Ocean Vuong, speaking about his younger brother

Frances Stark referred to her young son as an aesthete and used this to justify her crossing boundaries of “inappropriateness” (her love of Dance Hall, for instance), and I suspect that Casper, judging from his quick repartee as recounted by Justine in her road-tripping memoir, has something of that obsessive quality as well. My son, whom I’ve written about sparingly, is closer in type to the half-brother described by the poet Ocean Vuong. B knew at an early age that he did not want to be like his artist-parents; by all appearances he fell far from the tree.

Over half the plates in Highway Kind feature cars, most of them old school, many junked and rusting, many being worked on by young men, their limbs protruding from under the chassis. There are close-ups of motors and tires and decorative rims and paint jobs, and a shattered windshield with a gapping, jagged cavity titled Death Seat.

In late summer of 2021, B began driving to work in a used wagon; it was a stick shift, which he’d only just learned to operate. Barely a few weeks had gone by in the new car before he crossed the median on a country road and ploughed into a heavy dump truck pulling a trailer.

We’d been on a beach in Provincetown and came home to phones exploding with text messages and voicemails, from a county sheriff and a woman who lived near the dangerous curve where the vehicles collided. I could hear B talking in the background, he was conscious, but my partner, J, rightly gauging the severity of the injuries, jumped in the car and drove the six hours to the hospital in Middletown, NY.

Some hours later, a trauma nurse called and delivered an optimistic prognosis: B was out of surgery and awake. Meanwhile J, still on the road, was calling me on the other line. I switched over and told him the good news. Except that he’d just spoken with the surgeon, and it was more complicated, there’d been extenuating circumstances. Two neck vertebrae were fractured; a craniotomy had been performed to relieve a life-threatening epidural hematoma. If he hadn’t been own to hospital he might not have survived.

When I arrived the following day, B was heavily sedated but extremely lucid, and there were things he wanted to immediately get off his chest. He was getting pain meds every hour on demand, and when he overheard me whispering to the nurse, he said, “Mom, don’t interfere, I’ve got all these holes in my body. It’s Fentanyl o’clock.” I kept my mouth shut, but in a notebook I transcribed verbatim his conversation with J, in which they both referred to me as a vampire.

I can imagine that this accusation is something Justine might have had to contend with as well, thinking of the accounts in her writing of Casper becoming more and more disaffected with the process of being photographed, of all the ways he found to conceal his face, of needing to be bribed in order to consent to a picture.

J and I cared for B at home in the weeks following the stay in ICU. There is a photo of B outside the house, staples forming a giant question mark on the side of his head and across his forehead. He has the quasi-saintly look of a char- acter from a Dostoevsky novel.

A scarred and palsied young man in a collar and a Tacoma drug user stand before a camera and consent to be recorded. Most of the human subjects in Highway Kind are boys and men. And it is no coincidence that all the progeny in those written chronicles by Kurland, Nelson, Dodge, Gessen, and Stark – and my own story – involve young men left at risk, to one degree or another, or at least falling behind. The blame for this should not fall squarely on the mothers; it is a societal issue, ongoing for several decades, and an unspoken subtext of Highway Kind. I’d wager it is a theme that Justine will return to, when the moment is right to “feel it out loud.”

2 Moyra Davey, “Mothers,” exhibition pamphlet for You’re a nice guy to let me hold you like this, (London: greengrassi, 2015).

A Nice Guy

By Justine Kurland

I don’t see why the love between a mother and son should be any different from other kinds of love. Why we shouldn’t be allowed to stop loving each other. Why we shouldn’t be allowed to break up. I don’t see why we shouldn’t stop giving a shit, once and for all, about love, or so-called love, love in all its forms, even that one.

— Constance Debré, Love Me Tender

In her essay Mothers, Moyra Davey describes a scene in which her seventeen-year-old son B., slightly high, sits in her lap. Anyone who has had or was once an American teenager will recognize this as an extraordinary act of affection. She remembers telling him, “You’re a nice guy to let me hold you like this.” My son Casper, now seventeen, hasn’t spoken to me since he moved in with his father more than two years ago. I wanted Moyra to write about Highway Kind because I connected Casper, as-if-dead, to B.’s near-death crash last summer. I have a million reasons that it’s not my fault, but of course it is. How could all his anger and unhappiness not be on me? I wondered if Moyra felt this responsibility too, even for an accident.

I recall her description in Notes on Photography & Accident: “Flip[ping] through hundreds of contact sheets of my baby, wondering how I could have possibly taken so many pictures of him in the first few years of his life (a veritable compulsion is how it strikes me now). Still, these were the images I wanted to look at, pore over, scrutinize.” Later in the essay she considers “the contingency or sign that might allow us to read in the photographic record… a foretelling of [a] tragic end.”

If Casper sees himself in my scenes, might it be with a premonition of dread for something that will have already happened?

As Andrea Dworkin has put it, though women face different degrees of crisis, all possess a “primary emergency,” a “ first identity, the one which brings with it as part of its definition death.” Alice Notley has written that women are born dead. This goes double for any mother who prepares her son to blame her for his fate and prepares herself to accept his blame.

Born in 1969 in New York State, near Canada’s frontier, Justine Kurland is known for her utopian photographs of landscapes and the fringe communities, both real and imagined, that inhabit them. Her images reveal the double-edged nature of the American dream and navigate, as she has said about her most celebrated series, Girl Pictures (1997–2002), “the spectrum between the perfect and the real.” Her work has been exhibited extensively in the United States and abroad and is in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the International Center of Photography, and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, among other institutions. www.justinekurland.com

Moyra Davey’s work comprises the fields of photography, video, and writing. She is the author of Index Cards (2020), co-author of Davey-Hujar: The Shabbiness of Beauty (2021), and editor of Mother Reader: Essential Writings on Motherhood (2001). Davey’s work is held in major public collections, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; and Tate Modern, London. She is a 2020 John S. Guggenheim Fellow and a 2022 recipient of the Governor General’s Award.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 121 – WANDERINGS ]

[ Complete article, in digital version, available here: Justine Kurland, Highway Kind (A Love Story) — Moyra Davey, Young Men at Risk ]