[November 29, 2022]

By Michel Hardy-Vallée

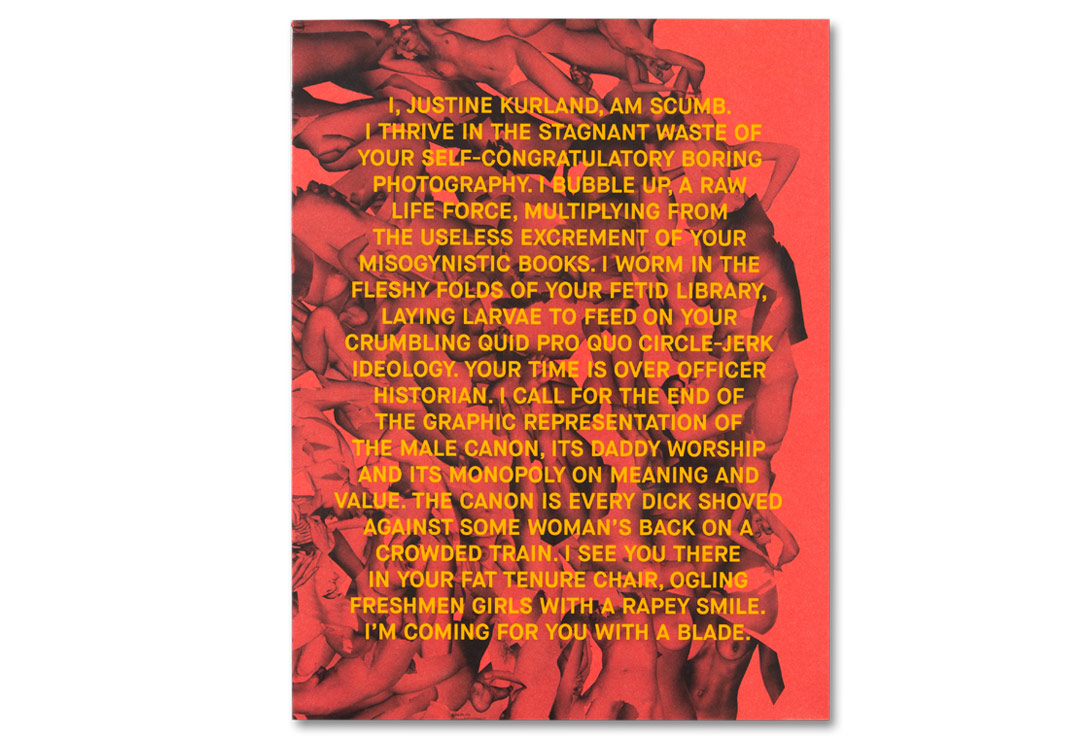

So, let’s review: Valerie Solanas wrote the radical feminist SCUM Manifesto (SCUM stands for Society for Cutting Up Men) in 1967 to protest how men were leading the world (to failure) and then shot Andy Warhol in 1968 because he was controlling her life and had, in her view, plagiarized a play that she had written. The exact facts probably don’t back up her version but, well, when it comes to celebrity, an eloquent lie is surely worth as much as a complicated truth. And now, let’s move on to Justine Kurland: after a catastrophic childhood, she began to travel. With her son. In reality, she began her road trips with a trailer, photographing marginal young people, and then got pregnant and eventually stopped travelling so much. Let’s start again: you’d have to be blind not to see that photography is a boys’ club. Most of the people I know who work in museums are women and most of the people whose works I’ve seen on museum walls are men. It’s a bit risky to take liberties with a work in a museum, but in a book? Why not? After all, books are a common consumer good; they are easily replaced.

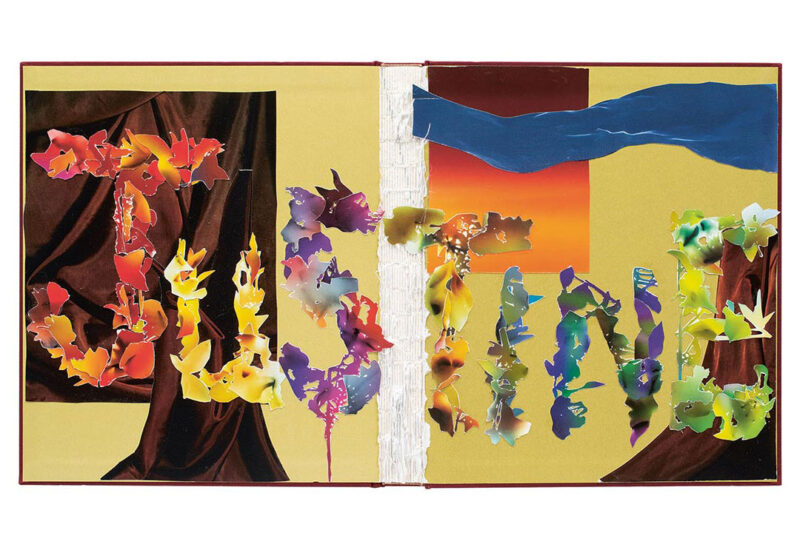

Justine Kurland, SCUMB Manifesto, London, MACK, 2022, 24.5 x 32 cm, perfect bound, offset lithography, 282 pp.

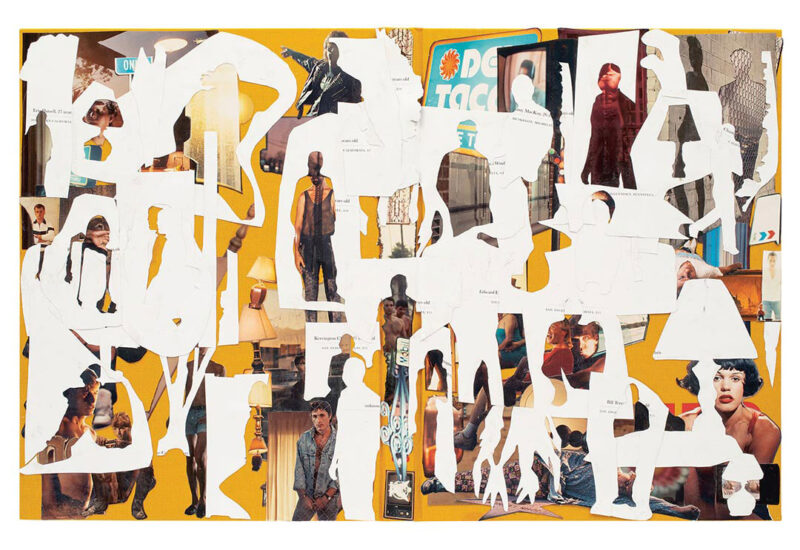

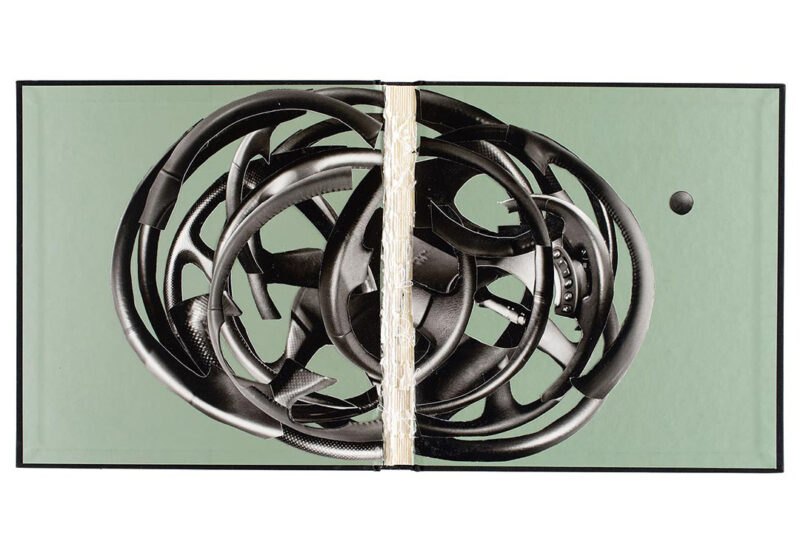

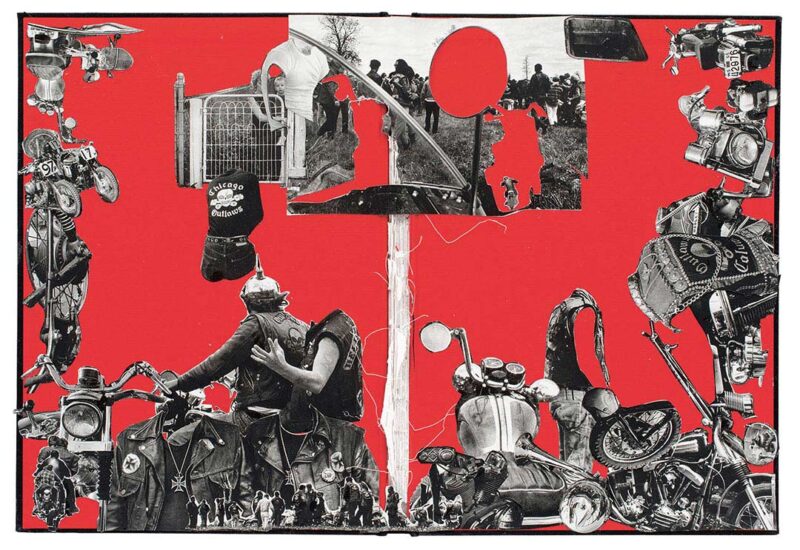

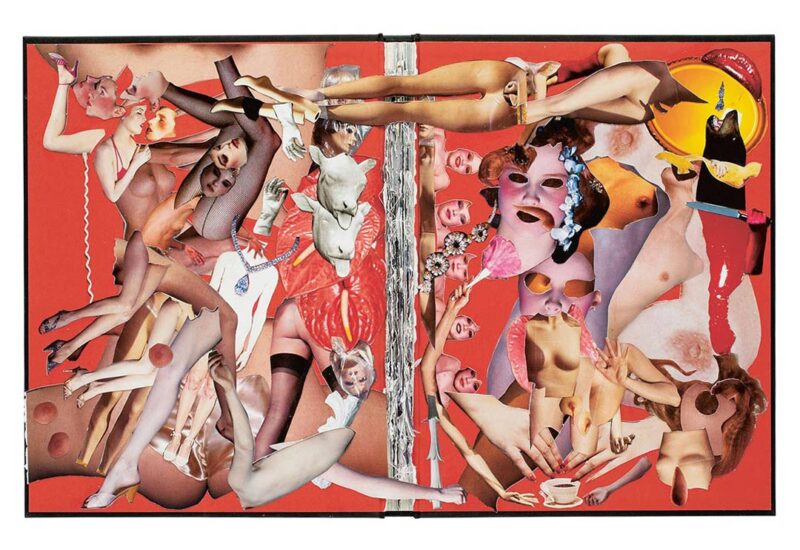

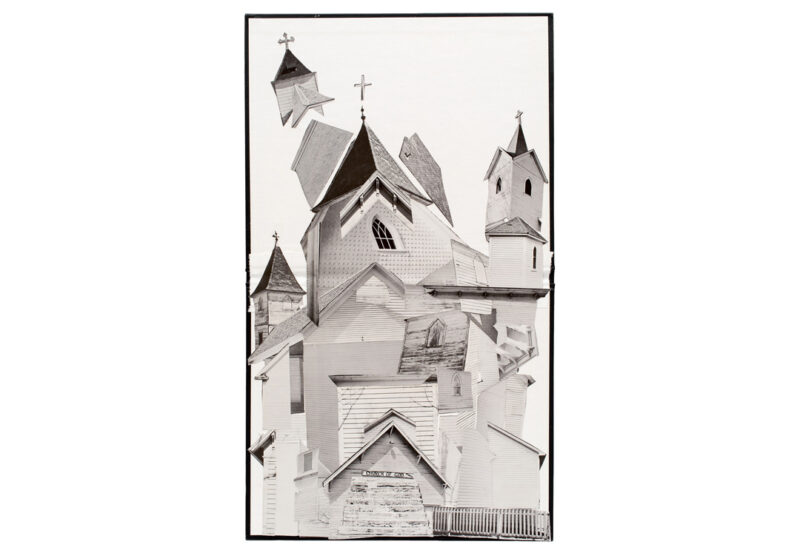

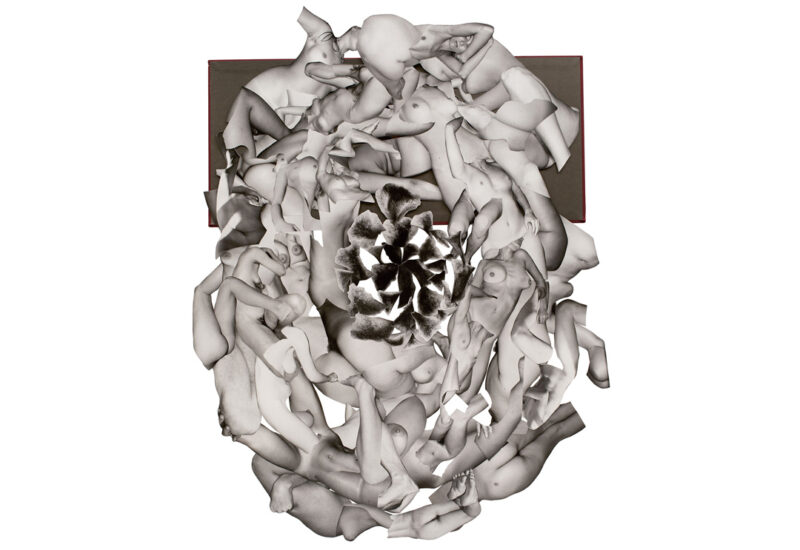

So, Kurland looks at her bookshelf and thinks of Solanas. Why not? There’s more than one way to cut men into pieces. She picks up her scissors and begins. She dismembers books, extracts fragments, sorts them, and then regroups them by affinity, as if she were editing a book of adages. A “cut-up” is a knife stabbed into copyright, a book prepared like John Cage’s pianos. It’s also a surrealistic juxtaposition, as in Max Ernst’s Une semaine de bonté or William Burroughs’s novels. If one cuts out all the pubic areas from the nudes in Lee Friedlander’s books (carefully reproduced in black-and-white three-plate offset printing, developed by Richard Benson), you end up with bushy shrubbery, almost a forest – a clear metaphor for the mania with hiding behind art to be a voyeur, a creepy old man, or possessive. What is Kurland’s most threatening act? Damaging books, targeting men photographers, fooling around with copyright, or not staying in her place? As a man (even if, in English, people sometimes assume the opposite when they pronounce my first name), I should feel threatened, but I don’t. The complacency and patriarchy that Kurland denounces belong just as much to those who called me a faggot in elementary school. I’ve never had patience for machismo, virility, and all the stupidities that keep men from being comfortable in their skin. Sexism, like racism, is a way of making people waste time. Collage can also become a political pastime.

And so, I read Kurland’s book SCUMB Manifesto, and without realizing it I look for books that I know. Here, it’s Eggleston; there, it’s Frank, and then Clark, and somewhere else it’s Shore (or maybe Soth; they’re kind of alike). Even diCorcia. Although I had thought he was trying to say something else with his male prostitutes. Have I gone astray? Has the cut-up simply recontextualized the boys’ club? The essays in the book that explain the approach are spaced out regularly so that I can understand the message between the collages. The reproductions are irreproachably clear: there’s no moiré effect between the existing screen of the books from which the images were cut out and that of SCUMB Manifesto. There’s not even a single photographer’s name in the index, just the titles of the books from which Kurland cut. Then I reconsider the sliced-up books, and they all share a fixation on the object, the representation of things: here, there’s no Duane Michals, who works between two images. With Kurland there is grammatology and the desire to defeat the logos, the certainty that the photograph can show something, such as, for Friedlander, Madonna’s crotch. So, when I seek the photobook object, I find it in SCUMB Manifesto; Kurland leaves the imagination alone.

Kurland wants us to lighten up, à la Dada. Winogrand takes it for his status and she roasts Weston. Here, there are rage and humour at the same time, because laughing does not come from a position of comfort. Is the problem mainly American, as her sampling suggests? As long we confine ourselves to considering the history of American history to be “the history of photography,” the problem concerns us all. Translated by Käthe Roth

Michel Hardy-Vallée is a historian of photography and Visiting Scholar at the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art, Concordia University. His research is concerned with photography books, visual narration, interdisciplinary practices, and the archive, in the contexts of Quebec and Canada. He has published his work in History of Photography and through a number of edited collections and conference papers. He is currently working on a monograph about John Max.