[December 12, 2023]

By Louis Perreault

In 2019, the American artist and author Jenny Odell published the delectable book How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. Beyond its intriguing title, this dense essay deals with sociology, art, and ecology and contains fantastic opportunities to consider new ways of conceiving the world in which we live. In one chapter, Odell relates her discovery of atmospheric rivers, a meteorological phenomenon that consists of a corridor of humid air flowing north from the tropics over thousands of kilometres, bringing rain when the water vapour cools and condenses. She sees in this an example of the porosity of borders in what she calls bioregionalism – the study of the natural specificities of a territory – as unperceived phenomena, some of them from distant places, are constantly disrupting and transforming places. The daughter of a Philippine immigrant, she says, “I remember that not only is my mother an immigrant, but that there is something immigrant about the air I breathe, the water I drink, the carbon in my bones, and the thoughts in my mind.”1

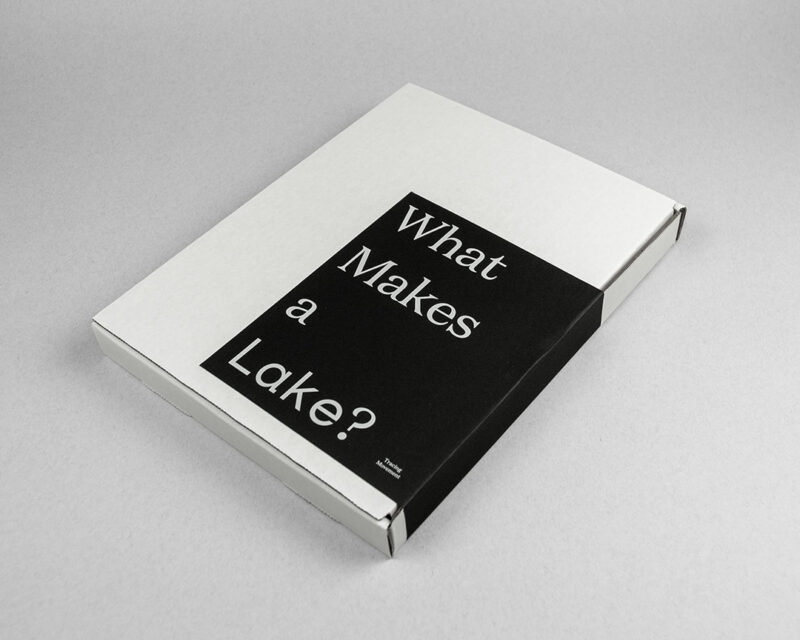

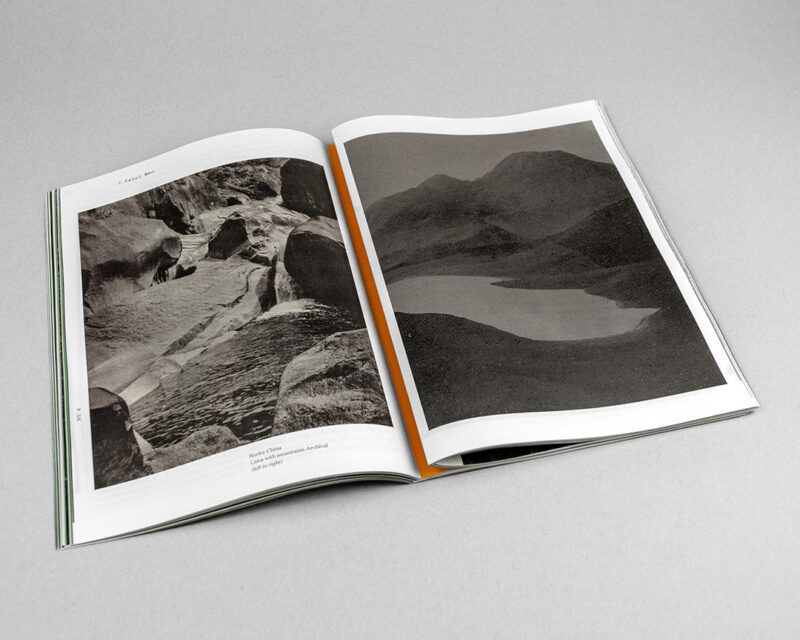

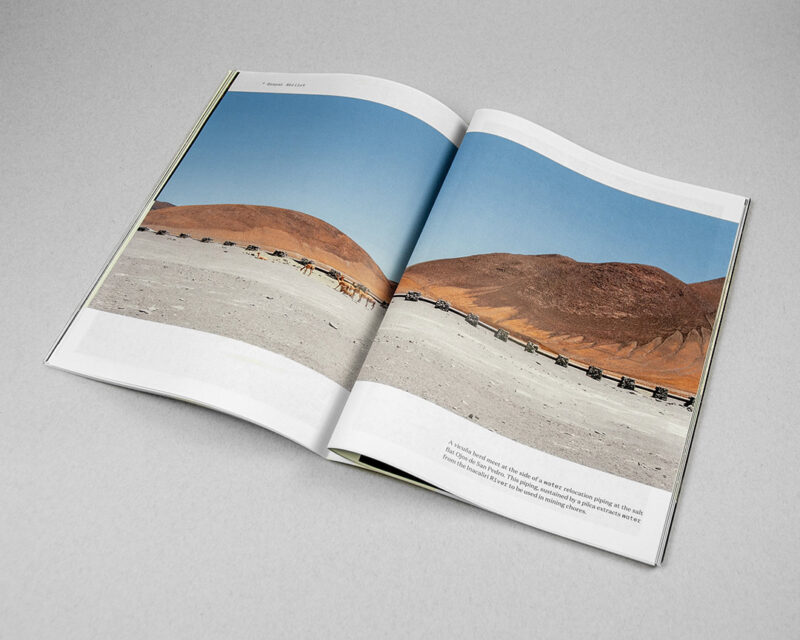

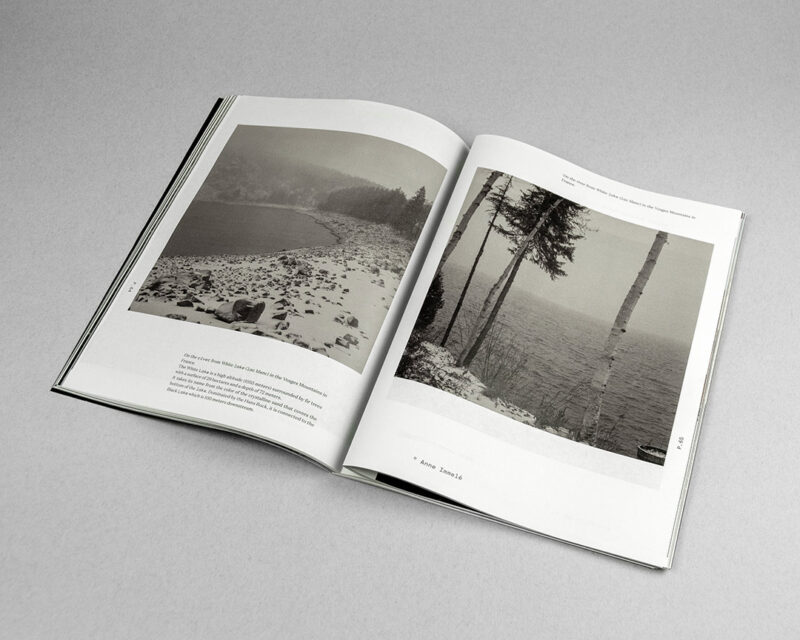

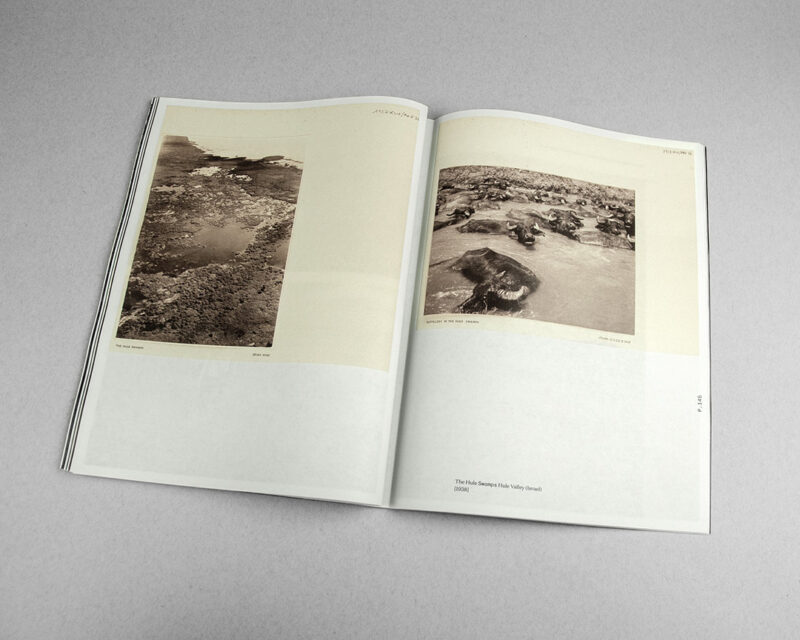

It was the premise of What Makes a Lake? Tracing Movement, published by Another Earth, that prompted me to read Odell’s book. In the introduction to What Makes a Lake?, an atypical publication (unbound, presented in a case with an imposing typographic design, assembling works by more than eighty artists), the instigators of the project – Abbey Meaker, Estefania Puerta, and Cristian Ordóñez – explore the many ways that lakes have been formed over the centuries. From volcanic eruptions that cause mountain peaks to collapse to natural dams that block rivers, to falling debris and landslides that transform valleys into basins, lakes, we are told, are created by multiple actions and circumstances. “A lake is what is left behind,” the authors write, “a response, an imprint, a historical document of what came before. While lakes communicate the past, they also represent the present health of the planet and its communities. In a sense, lakes keep time.”

We learn that when we study lakes we are forced to recognize the importance of the organisms that live in them, the minerals that form their shores, the birds that fly over them, the human beings who fish or swim in them, and all the memories and stories that continue to place them in the centre of scenes that we talk about. Thus, what was initially intended to be a project about Lake Champlain, near which two of the publication’s editors live, was transformed in a much broader investigation of the different ways of understanding lakes – from environmental, socio-historical, naturalist, personal, narrative, and other points of view. A call for contributions was launched on the editors’ social media, and an impressive quantity of photographs, archival documents and images, texts, poems, and essays were collected, leading to a broad and eclectic definition of what makes a lake.

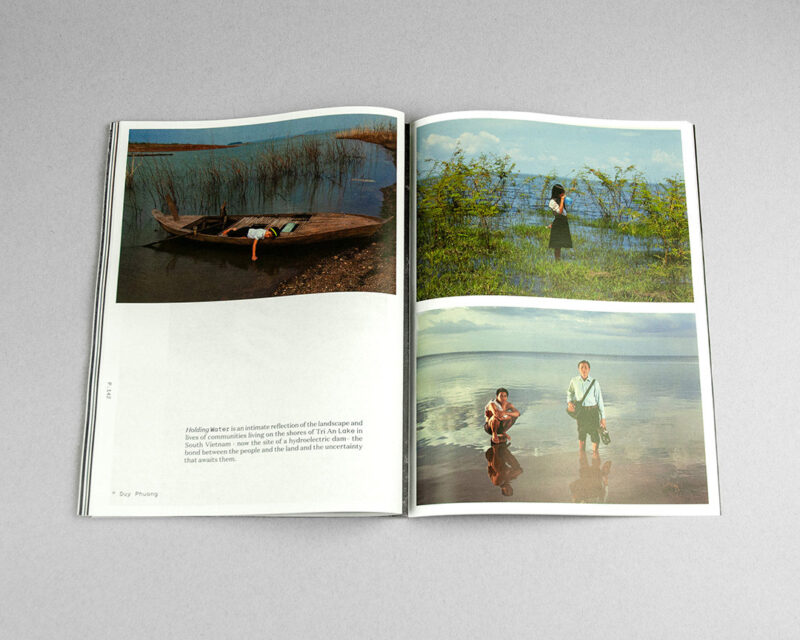

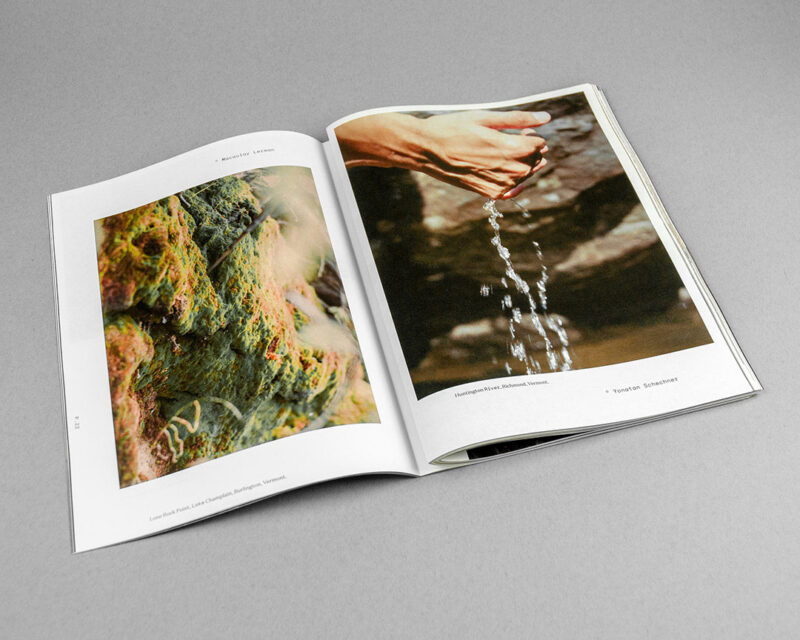

The book offers stories, photographs, and information about watercourses in many world regions. Some of what we read is poetic, some marked by the tragedy of global warming, but overall we are struck by the contributors’ sense of wonderment about the natural world. The poet Roman Gioglio expresses his sadness about the evaporation of waters that were precious to him (“the last lap from the final wind-struck ripple / bellies up onto the ice / and sighs out the sorrows of the entire world, / freezing into a position /that looks more like praise”), and the author Koan Brink dives into memories of Lake Michigan through an archival photograph that shows her grandmother, with her two sons, swimming there for the last time before moving to the prairies of Iowa. Surprised to discover the “residence time” of particles living in water, Brink is amazed to touch “a pool of 99-year-old particles.” Here, the lake is a vector of imagination as much as a source of knowledge, just as it is the visual material for this content-rich and reflection-inducing publication.

The book goes beyond raising awareness of the richness represented by water in all its forms, from the smallest stream to the vastest ocean; it provides a space for deep contemplation on the very definition of that which we name in any study of nature. It allows us to recognize the interrelationships among various phenomena, both “natural” and social. Like Odell appreciating atmospheric rivers, the authors, artists, and editors of the book embark upon a path that breaks down the essentialist borders of the world. Odell, for her part, continues her thoughts: “An ecological understanding allows us to identify ‘things’ – rain, cloud, river – at the same time that it reminds us that these identities are fluid … When we really get down to it, all we can really point to is a series of flows and relationships that sometimes intersect and hold together long enough to be a ‘cloud.’”2 All we have to do is replace the last word and we would have the beginning of an answer to the question What makes a lake? Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Ibid., 151.

Louis Perreault lives and works in Montreal. His practice is deployed within his personal photographic projects and in publishing projects to which he contributes through Éditions du Renard, which he founded in 2012. He teaches photography at Cégep André-Laurendeau and is a regular contributor to Ciel variable, for which he reviews recently published photobooks.