[Winter 1993]

by Claire Gravel

For a quarter of a century has been relentlessly photographing the same set of landscapes, all of whose horizons include the St. Lawrence River. At first glance, it seems that these untamed locales in contrast to the mere simulacrum that is every work of art reaffirm the permanence of the world.

In the early sixties, Michel Hébert drew and painted from photographs, going with the prevailing current of hyperrealism. His experience at L’école des Beaux-arts de Québec would be a decisive time for his study of photography. A preference for working with the intensity of values won out over tones.

Michel Hébert’s first works were notable for his fineness of penciling that imitated the grain of the model photograph. Later, we would see photomontages where his symbolic structuring of elements remained responsive to the nature/culture antinomy of the intellectual investigations of the time.

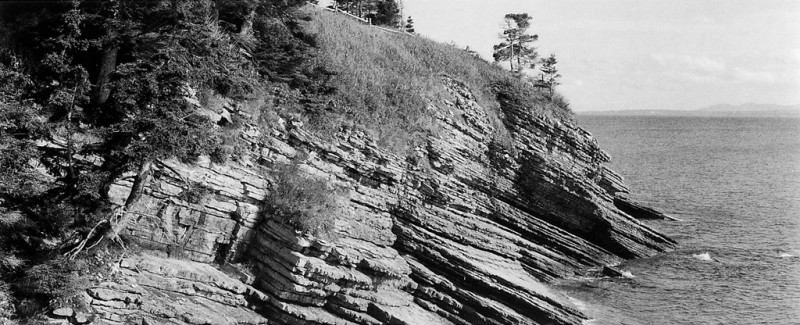

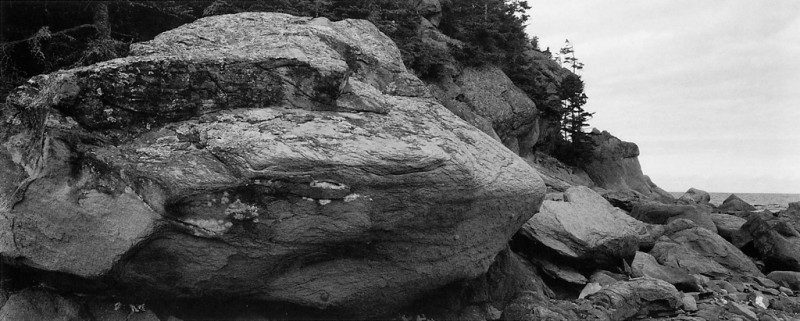

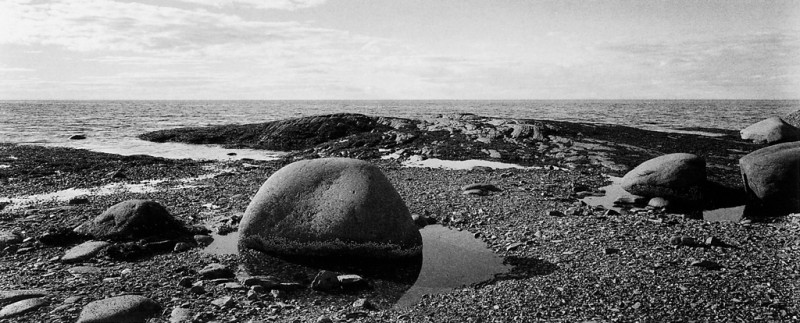

In 1968, one drawing presented a cut-out view of reality through the viewfinder of a 2 1/4×2 1/4 inch camera: the focus is fixed on the landscape, leaving the people a blur. This “trompe l’oeil” reveals a struggle between his subjects and in the end, human bodies would be banished from his views and the landscape itself magnified through very meticulous cropping, leaving only a incredible visual remainder where all the subtle shades of grey unfold moments of splendour that our eyes pass over without seeing as this phosphorescence of luminous particles and these awkward panoramic views conspire to flatten all contrasts. No more overwhelming blacks or whites, but greys that whisper; the lustres of pearls; an infinite plasticity of modulations and textures. That which is near appears far; the panoramic elongation intensifies the strangeness of the scenic model of the views because the narrowing of the point of view and the cropping during printing create a more “abstract” vision. Something becomes lost. The image shines from within — stronger yet than what was lost and it attains the quintessence of scenic portrayal; this loss bespeaks the origin and its inscription in a mythical “other-world” where the perceptions of the photographer and the viewer meet. Michel Hébert rightly speaks of “show images” that draw us in and carry us off.

In The Anti-panoramic we seem to be looking down from a great altitude at nature, when in reality the opposite is true: we are grazing a terrain of fissures and algae engorged from the last tide.

Before the endlessly-receding view of layers of ice in Of Piled Ice, we can no longer recognize where we are in this crystallized view of contradictory movements that transform the river into plas-tery layers.

Hébert acknowledges the influence of Edward Weston and of an American photographic style of the forties wherein the images of clouds, fragments of boulders and of the Mojave desert share the same direct, “puristic” and patient approach to nature.

“One must feel definitely, fully, before the exposure,” Weston wrote, and Hébert also speaks of an intuitive approach, of photographs that are the product of an introspection, of locales chosen because of a certain feeling.

Though he uses the 4×5 inch format, Hébert picks out his images with the aid of a cardboard mask attached to the ground glass that restores the panoramic format. This mask is similar to eyewear worn by the Inuit in winter. The image area of the cut-out is recreated in the darkroom.

There is definitely a construction of reality. This reality is not so “crude”: the “representational structure” that Victor Burgin describes in Thinking Photography is endowed with a performative character, a romantic stylization.

The very act of framing is, of course, a relic of his pictorial composition. For the last three years, Michel Hébert has been trying to recreate a sense of wholeness with his panoramas. The paradox of the reduction effected by the cropping breathes new life and the awareness of the universal into this totality born of the fragment.

Hébert frames his image even before it is fixed on the film; the image must submit to a structuring of reality before its recording. The head-to-head struggle that takes place once again in the darkroom serves to redouble the creative act and to reinforce the impression of a deliberate work.

On top of the “motif” dear to painters, the virtual picture (with the mask) has transformed the physical taking of the picture into an act of thought. Next, the framing puts back the memory of these “different” images, restores a vision of the “that was,” that wasn’t “that.”

Hébert is committed to bringing back the modulation of the photographic greys, the absence of the shadow and the light this decisive moment where the dullest scenery becomes breathtaking. He undertakes the reconstruction of the forgotten image, the chosen image before the image the rediscovery of the original place.

“I keep coming back to the same places,” says the artist. “[The] Forillon [park in the Gaspé region] is invested with an atmosphere that for me is a point of reference. The Gaspeseans have lived under very harsh conditions there; the rigours of the climate of the Bas-St-Laurent area are twice as severe there. The [St. Lawrence] river is a sea in this area. [When] there isn’t a breath of wind… you feel the rumbling of the waves, their sounds.”

“The pebbles are heavily-worn pieces of cliff-face. The winds move in every conceivable way; the temperature changes from one hour to the next.”

Always going back, always changing. Michel Hébert’s recent works are in the fashion of the landscapes of rock and the silence that they depict: shimmering imprints frozen for eternity in the silver salts.

Michel Hébert has been teaching for many years at the Collège d’enseignement général et professionnel de Matane in Eastern Quebec. His images reveal a profound capacity for observation and are the result of his great meticulousness in producing them. Since 1967 the artist has shown his work in numerous solo and group exhibitions. His work was recently seen in September, 1993 in one of the exhibitions presented as part of the le Mois de la Photo à Montréal event Hébert is a specialist in photographic sensitometry and the Zone System, and in addition to his creative work and his teaching he is currently working on a treatise expounding upon these two important techniques of contemporary photography.

A professor of art history, critic, and curator of present-day art, Claire Gravel holds a doctorate in aesthetics from the Université de Paris-X (1984). She has published numerous articles about photography in the Montreal daily Le Devoir (1987-1991), as well as in specialized magazines (Flash Art, Les Herbes Rouges, and Vie des arts).