[Winter 2005-2006]

Le mois de la photo à Montréal

September 8–October 10, 2005

Montreal’s biennial of photography marks its ninth edition this year under the artistic stewardship of Martha Langford, founding director and former chief curator of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography (1983–94).

It takes someone with Langford’s expertise to curate what has become a behemoth event, sprawling as it does across a large number of small and large art spaces in the city. With twenty-six individual shows and over fifty artists, the festival has become so big that it’s hard to assess what viewers actually get to see or which events they attend in a long list of openings, artists’ talks, and panels, as well as a two-day conference. Granted, the nature of festivals is such that they create amorphous and mobile audiences that are free to choose their focus, but it seems that Le Mois’s ambitions may need some curbing (for instance, this year a bus shuttled gallery goers between openings). Nevertheless, the festival’s endurance proves that it has the ability to mount such an extravagant enterprise. Its continued existence is assisted in great part by dedicated and capable staff, including administrative director Chuck Samuels, and sustained financial support, especially from provincial and municipal sources.

This year’s theme, “Image and Imagination,” is, as Langford suggests, a challenge to nay-sayers who refuse to accept that photography, regardless of the many crimes that can be attributed to its deceitful nature, continues to be about creativity, for both the artist and the viewer. This, she suggests, is a good and necessary thing. As artistic director, she has attempted to impose order and logic over the pluralism of formal strategies and subjects that threaten to undermine the integrity of the whole by devising a conceptual frame based on three sub-themes: “Sightlines into the Imagination,” “Mirroring Ourselves, Recasting Otherness,” and “Pictures as a Way of Shutting Our Eyes.” However, it’s unlikely that viewers heeded this attempt to structure their viewing experience; the conceptual ideal was too easily thwarted by circumstance – an expired spotlight or broken projector, a gallery that was a little too far away to bother with.

The conceptual depth and complexity of the overall thematic structure is perhaps best seen in the splendidly produced catalogue that accompanies the festival. The decision to go with an academic press suggests that Langford wanted a “book” rather than a “catalogue” (the academic turn is also revealed by the Ph.D. credentials attached to many of the participants’ names). The book concept likely explains why some of the writings do not directly relate to artists or works on display but instead serve as “theoretical guides” for the viewer. Langford’s own intellectually acute writings are interspersed among essays by internationally known writers such as Geoffrey Batchen and Ian Walker. In keeping with Le Mois’s tradition, the exhibition and catalogue give ample space to emerging and established artists and writers, both local and foreign.

In the past, the festival’s aspiration to international status has tended to cast the spotlight on European artists, so this year’s shift to the Australian scene is a welcome and significant achievement. Australia’s participation raises issues about relations between the “old” and “new” worlds. The most compelling works in this area of inquiry are the disconcerting still lifes by the Australian artist Destiny Deacon (uncomfortably paired with Evergon), whose brazen images attack the painful legacy of racial bigotry. Post-colonialist identity, and its critique, is also raised elsewhere at the festival, in the work of Matthew and Hulleah, and it is foregrounded in the group show Emanations. It seems a missed opportunity not to have addressed Canada’s own colonial past more directly, given the similarity in our two countries’ histories, although one can read curator Vincent Lavoie’s Primal Images in this context (but one wonders how many of Le Mois’s audience actually saw this museum show, given its hefty ticket price).

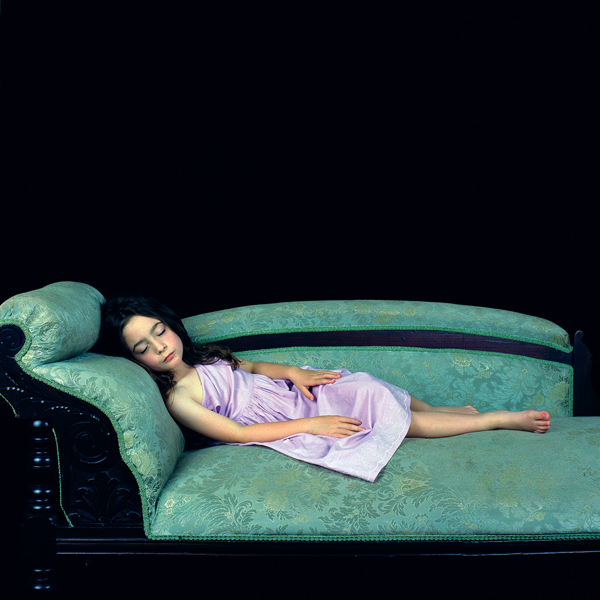

The subject of sexual violence underscores Deacon’s work and that of fellow Australian Tracey Moffatt in her exquisitely produced reveries of seduction. It is also in After Alice, a two-person show about children and predatory fantasy that includes the Australian Polixeni Papapetrou. The subject of sexual relations appears again most apparently in Karen Brett’s tightly framed, large-scale photographs of older couples’ blushing bodies, and even in Michael Snow’s colossal curtain-piece Powers of Two. Some deliver their intimate message by turning the camera on themselves, as seen in George Steeves’s searing photographs in the group show Little Histories (although in this context the impact of his work seems somehow reduced), and in Evergon’s little theatre of the self, similar to Steeves’s, created so that he may deliver a sage soliloquy on the nature of time and desire.

Others have also chosen to focus on themselves. Diane Borsato’s witty and intelligent performance-based work seamlessly fuses conceptual strategies with personal narrative. What could easily have failed succeeds because the formal strength of her work lies in its deceptive simplicity. Borsato’s lightness of being contrasts with Raphael Goldchain’s disturbingly beautiful false portraits in the group show Trading Places. Using himself as model, he has created large-format portraits that trace a fractured family past. Like nervous visitors approaching a casket, we are plunged into the images’ velvety, morbid depths. Alain Bublex’s monumental Glooscap, a city he has invented along with its history and archival record, evokes similar elegiac sentiments. The magnitude of Bublex’s confabulation is impressive even as it reveals the melancholic delusion at its heart: the impossible search for “home.” Donigan Cumming’s mammoth painted collages present another astonishing universe, peopled by hundreds of familiar faces from the gene pool that is his own photographic archive. Others looking back at us are what we encounter as well in Gabor Szilasi’s collaborative project Les Impatients, a unique project within the festival’s essentially individualist approach to artmaking.

That we perpetually struggle to orient ourselves in a landscape that grows increasingly foreign is the subject of several artists’ works, from the urban encounters in Neverlands, Digs in the Zone, and Catherine Bodmer’s muddy scenes to the phenomenological studies of urban spaces by Denis Farley in the two-person show JimÆ and the digital panorama of Ramona Ramcholand’s global odyssey. Perhaps no work captures the sense of postmodern vertigo as much as Lynn Marsh’s dizzying but immensely satisfying video installation Crater.

As in the past, this year’s festival includes a fair sampling of new-media work. While Carollee Schneemann’s complex of moving displays seems overproduced and Marc Audette’s eerily luminous screens are too cramped in their space, Adad Hannah’s setup of projectors (almost an installation piece on their own) progressively dislodges fictive layers of the photographic real in Cuba Still (Remake). Two recent video pieces by Michael Snow produce the kind of perceptual dislocation that we expect from “new media,” which, the thematic retrospective Windows tells us, is really an old idea to Snow. Langford’s attention to this artist (a coup for the festival) stems from her longstanding admiration of his work and her fascination with his use of windows as formal and conceptual tropes in his production. The Snow show Windows finds its complement in Iain Baxter&. This gem of a show, curated by Mare-Josée Jean, is an overview of Baxter’s interdisciplinary career, which, like Snow’s, emerged out of the singularly innovative and productive period that we call “’60s art.”

Another amusing and “instructive” show is Little Histories of Modern Art. With eight artists, it is the largest of the shows and, as its title indicates, is presented as an abbreviated lesson on postmodernist photography. It includes Colwyn Griffth’s fastfood-scapes, Jakub Dolejs’s slick parodies of academic painting, and Holly King’s intoxicating facsimiles of nature, among others. David Hylinsky’s solo show Rosebud, a parable about corporate greed and misaligned mythologies, greets us before we arrive at Little Histories. Langford’s declaration that a “liberation in the sensorium” of photographic practice is underway is certainly reflected in the range of approaches present in Little Histories and elsewhere at the festival. However, of the group shows, Trading Places appears the most cohesive, due in part to its accommodating space and the generous number of works allowed to each of the four artists. The show explores the parodic in contemporary practice through works such as Anna Matthew’s restaging of Edward Curtis photographs, although the award for funniest, most biting satire in the entire festival must go to Michael Ensminger, whose work is also in this show. Les Revenants, a group show about ghosts, the dead, and other ineffable types, seems, in comparison, to be an anomalous assortment of images; too few in a too dim space, they don’t manage to produce a coherent collective message. In contrast, Oil and Water is crowded even with only three participants (Michael Flomen’s work deserved to stand alone). There are other shows that don’t seem to gel, such as the previously mentioned Emanations, in which the artworks are forced into awkward spaces, and the ParkeHarrisons’ From The Architect’s Brother, which was shown in a space so off the beaten track that one questions the reason for its inclusion.

There are endless ways to imagine an ideal photography festival, but given the realities of such an undertaking Martha Langford and her team have done an outstanding job; they have been professional in their organization and ambitious in their reach. This year’s Le Mois de la Photo has ventured into new territory by introducing Australian photography, taking on more museological projects (Snow, Baxter, and Primal Images), and producing a superb catalogue, all the while maintaining its commitment to the Montreal community of artists, viewers, and spaces to which it owes its start.

Anna Carlevaris lives and works in Montreal.