[Summer 2003]

March 13–April 21, 2003

Anyone looking for photographs at the fifth international Foto Biënnale Rotterdam (FBR), titled Experience, would have left the two main exhibition sites in a hurry. Photo aficionados would have had better luck at the many participating galleries and museums throughout the city that opted for more traditional exhibitions. Few still images were to be found at the Nederlands Foto Museum, the institution that organized the biennale, and at Las Palmas, a huge obsolete harbour warehouse, which is also the future home of the museum. Shown were not just the by-now-familiar border crossings between photograph and video, in works by Alfredo Jaar, Bill Viola, and Osamu Kanemura, among others, but there were also video-game machines, a marketing-research film, computer installations, and several displays that would not have been out of place in a technology trade fair. There was even a real-size reconstruction of the living room used in the reality TV series Big Brother, which originated in the Netherlands.

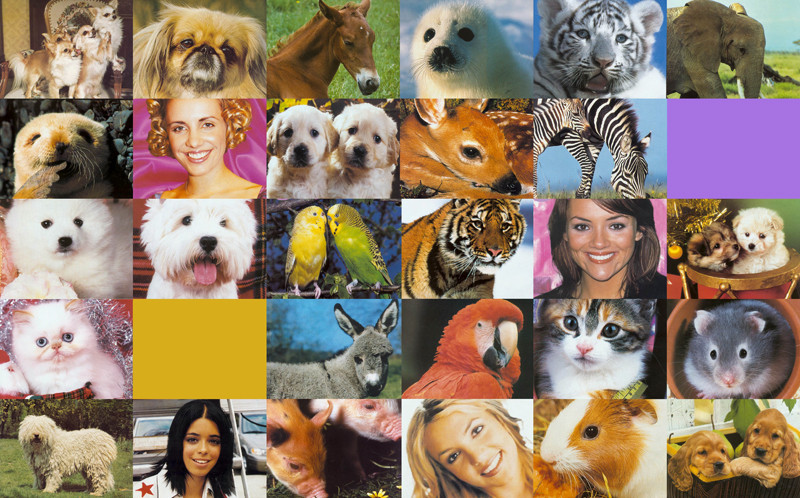

Curators Frits Gierstberg and Bas Vroege deliberately broke away from the tight categorization of a photo exhibition in order to place the still photographic image in the wider context of contemporary visual culture. They explained in their catalogue essay that the intent was to show how the flood of images that is created daily, whether for entertainment, information, surveillance, commercial, or aesthetic purposes, influences and shapes our thinking and behaviour. To cope with this overload, we are forced to develop a “mental filter” to sift out unwanted visual impressions. A “media rat race” ensues, in which advertisers, entertainers, and artists alike develop strategies to break through these filters in order to reach an audience. Experience reflected the image culture we live in by intermingling commercial products and services with art installations. “The similarities in strategy, concept and realization,” the curators wrote, “are often striking.”

Using the exhibition site as a flashpoint, Gierstberg and Vroege chose to use the FBR to open an interdisciplinary discussion on an important cultural issue in which photography is inextricably interwoven. Lectures, discussion groups, participatory events, and a publication formed an integral part of this investigation. Rather than illustrating theoretical ideas, the visual displays demonstrated the way in which our thinking and behaviour are influenced by images in a media-saturated society.

The bilingual (Dutch/English) catalogue, Experience, the Media Rat Race1, provided a clear curatorial essay as well as a number of critical papers on the relationship between media and reality. Some of these focus on ways in which new technology and media tap into people’s impossible desire to experience authentic reality. The media promise to make everything visible, and visibility becomes a substitute for experience. Francisco van Jole writes on reality TV and the disappearance of the story; Jennifer Cypher and Eric Higgs, on Disney’s Wilderness Lodge as an extreme model of presenting and selling constructed experiences. What is made visible is often an artificial reality, presented as authentic and largely tied to ideological and commercial interests. In his essay “Closed Circuits,” Timothy Druckrey warns of the insidious paranoia of an info sphere that strives for total control in a sheer transparent public realm in which every individual becomes a potential suspect.

Not every contributor to the catalogue appears convinced, however, that visibility as a substitute for experience is necessarily a bad thing. Arjen Mulder, in “Trance of Photography,” appears less critical of the image society. Mulder argues that we yearn not at all for an authentic experience, but for “a direct experience of something we are not,” a trance-like experience engendered by the indefinable other-worldliness that the media provide.

Gierstberg and Vroege abstain from a critical viewpoint as well. Their approach in the catalogue essay, as well as in the exhibition itself, is to provide a demonstration of the new media order, leaving critical judgment to the readers/visitors.

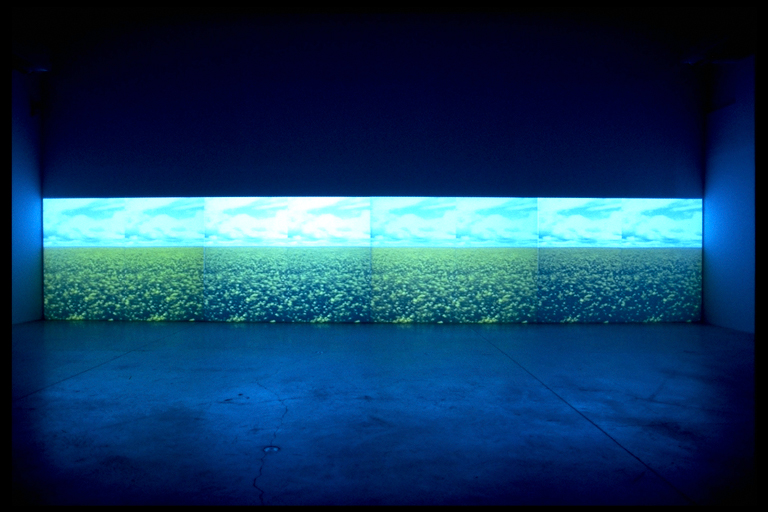

Of the several filter-busting strategies discussed by Gierstberg and Vroege, immersion is highlighted in the exhibition. The strategy of immersion is a way of creating a total “experience,” stage-managed events, through the creation of an enclosed environment in which one is shielded from competing imagery and impressions.

The exhibition design facilitated the immersion experience. F.A.T. (Fashion, Architecture, Taste), a London-based architecture collective, created functional plywood cubes for most of the contributors, while surrounding other works in transparent curtains. Upon entering each enclosure, the visitor is left with one particular installation, whether this was a showcase of Vodafone’s mobile phone advertising campaign, a montage of magnified one-second video-shots of Tokyo by Osamu Kanemura, or a single photograph by Rineke Dijkstra displayed in a white cube.

Gerald Van Der Kaap’s “chill terminal” Total Hoverty crystallized the immersion experience of the exhibition as a whole. When the visitor lay down on a bed and stuck her head in a vertical tube, she was treated to a stream of widely divergent, innocuous imagery that confounded any kind of meaning-making. Sights and sounds merely washed over the head caught in the image machine, providing an environment in which one could lose oneself and experience nothing but the media themselves. Gierstberg and Vroege identify this phenomenon as “looking without seeing” (p. 21). “Meaning,” appears to be an outdated concept left, according to them, to “the lost generation of ‘Barthesians’ – an audience searching for a deeper meaning or a ‘secret code’ which legitimizes the existence of the image” (p. 21).

Members of that lost generation (including myself) were bound to find Experience disturbing and rather depressing. The equivalence between commercial, entertaining, informational, and artistic enterprises that was demonstrated here upset a dearly held idea of a noble, subversive role for art. Thrown into the arena with all the other image makers, artists must compete to “subvert or overpower the ‘media-survival filter’ of the modern media-aware citizen” (p. 33). Experience suggested that only strategies can be subverted, and that meaning (or McLuhan’s “message,” if you will) is unavoidably sacrificed to the media. What is worse, when it comes to immersion, art may even have taught the commercial world a thing or two. After all, art exhibitions thrived in secluded white (and later, black) cubes long before the commercial world caught on to the power of this shielding strategy.

But, as is the case with Jean Baudrillard’s scary tales of the “society of the spectacle,” Experience shows us a mirror of a plausible future in order to provoke pointed questions about where we are heading in the present. Is this really where our society is going? Have we traded our modernist myths of individuality and expression for this complete loss of self and agency? And has art definitely lost its capacity to counter the ideological forces of a consumer-driven society?

Experience was presented as a coherent cautionary tale of a dispirited society stuck in a visual moment in which nothing but the media themselves can be experienced. But as the catalogue provided contradictory points of view, so the exhibition itself allowed for contradictions from within: individual contributions tore at the seams of the tight curatorial package, adding a vital dynamic to the show. The tugging came primarily from works of art that used the flickering, shiny imagery as a strategy to connect to a life that is larger, more ancient than the life of new media and that is hardly containable within the immersive enclosures.

Viola’s “The Quintet of the Silent” (2000) is a video loop that shows a group of five men expressing horror, bewilderment, and surprise. At first it appears to be a still image, strongly reminiscent of early Renaissance paintings. Then, extremely slow movement is detected and the image becomes a tableau vivant, linking age-old ways of portraying human emotions with a medium of the present.

Bruce Mau’s “Stress,” a video installation created with André Lepecki and Kyo Maclear that was earlier seen at the Power Plant in Toronto, also injected history into the pervading sense of the present moment that Experience emphasized in the rest of the exhibition. In a brilliant montage of archival film and photo material, text and sound, “Stress” shows a history of inventions, war trauma, and technological experiments, such as the electrocution of Topsey the Elephant on Coney Island in 1903, that helped to shape the media society. While in the exhibition at large this society is shown as ahistorical, an inevitable, naturalized state of affairs, “Stress” provided the specific historical development that led to it.

The immersive environment that Experience created also filtered out the majority of the world population that is not wired for the image society. There is no suggestion, for example, that the clothing with built-in mobile phones and audio-players designed by Phillips and Nike would be experienced differently in a country where such things are bought and worn than in the poor countries where they are manufactured.

Only the work of Jaar broke with this Western ethnocentrism. The blindingly white light that filled a wall of his installation appeared at first to be a void, a space empty of images. As was explained in a accompanying text, this void referred to the absence of images of the 1994 Rwanda genocide in the Corbis photo archive acquired by Bill Gates. Almost imperceptibly at first, a portrait emerges from the light. It is the face of Caritas Namazuru, who was eighty-eight years old at the time the photograph was taken during the time of the genocide and who had just walked three hundred and six kilometres.

To me, the old Barthesian, Jaar’s photograph formed a punctum in the exhibition, an abrupt reminder of real feelings, individual suffering, and heroic survival that pierced through the flood of imagery of Experience and forged a connection with life outside the image. And so there remains, perhaps, a future for art.

The FBR’s remarkable lack of photographs appears to question the future of the photo biennale itself. Sprung from a tradition of showcasing artists who could be neatly categorized by nationality and/or medium, biennales seem better suited to times and places more tractable than our own. Few, if any, traditional artistic categories make sense in the globalized, computerized twenty-first century. Curators now have access to overwhelming artistic output from all corners of the world, while selection criteria are, at best, endlessly debatable. Too much art, too few standards: it seems a recipe for confusing and overwhelming exhibitions.

Cynics will say that it is nothing but tourist dollars and the inner logic of sequentially planned events that ensure the survival of such large international art events. But in recent years, the best of these exhibitions have forged a new investigative function for themselves that is more in keeping with the needs of our time. The fifth FBR made a valuable contribution to this trend.

1 Frits Gierstberg and Bas Vroege, eds., Experience, The Media Rat Race (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers/Nederlands fotomuseum 2003).