[Summer 2002]

Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001, 241 p.

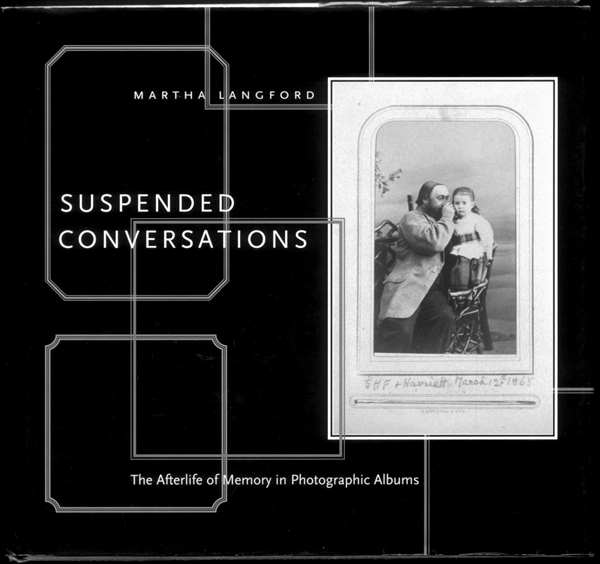

Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums is a remarkable book. Distinguished not only by its range and depth, but by the passionate commitment of its researcher, the publication concludes a ten-year investigation into the oral dimensions of amateur photography. Primarily concerned with the historical analysis of amateur photographic albums, the study encompasses many related themes: the social aspects of collection, leisure activities in Victorian and Edwardian society, changing ideas of family, the beginnings of automobility, colonialism, postcolonialism, and, of course, the memorial function of photography. Most significantly, Suspended Conversations examines the personal album with reference to Canadian historical artifacts: Examples are drawn from the Notman Photographic Archives at the McCord Museum of Canadian History. The book thus also elaborates a social history of Canadian photographic practice, told via the accounts of individual citizens.

The project evolved from an encounter with an anonymous album found in the museum. “Poring over the album for clues to its origins,” Langford writes, “one is struck by the irony of a direct equivalence between intimacy and loss.” Where once the pictures pasted in its pages were so familiar to its compiler that there was no need to annotate them, in the museum the names, dates, places, and stories that once animated them had become lost to time; abandonment had quieted them. Langford sought to find an analytic method that would reactivate them.

The book’s thesis builds upon the singular but significant observation that the album is a vehicle for an “oral-photographic performance.” Storytelling is the raison d’être of this private historical form. As such, Langford argues, the production of amateur photographs and photograph albums has a closer affinity to oral traditions than to literary production, with which they have, more typically, been aligned. Since writing requires close adherence to the rules of language – to cultural norms and social regulations – literary expression is said to reflect collective values. Speech, on the other hand, represents the interpretation of the rules of language by the individual.

Given the more egalitarian nature of oral expression, Langford’s literature survey reveals a surprising predisposition within cultural studies to the textual model. Coincidentally, the amateur photograph is read as an expression of dominant ideals. As Langford notes, “Most references to personal albums in photographic literature and works of art tend to replace the personal with the collective.” Pierre Bourdieu’s Un art moyen (1965) set the tone of recent scholarship early on: “All the unique experiences that give the individual memory the particularity of a secret are banished from” the family album.

Langford advocates a composite approach, combining textual analysis with a method that she describes as “recitation.” On the one hand, we “read” the album: annotating, interpreting, and comparing available information. On the other, we consider how the album’s author may have already interpreted this information in his or her compilation. The oral-photographic framework seeks out the mnemonic structures that ease oral expression, characteristics that also define individual identity. Expressive patterns of inclusion, association, and presentation in the compilation are compared to the repeated themes, associations, and turns of phrase that give character to individual speech.

Langford’s overarching objective is to tease out the specific expressions of individual users of the album from the generalizing tendencies of its conventional forms. Hence, the study observes the tensions at play between the governing “idea of an album” and its actual application. The book includes a series of chapters devoted to the four principal album types – collections, memoirs, travelogues, and family histories – and an extended analysis of one album that combines the features of all. This is the heart of the study, and, not coincidentally, the album that initially inspired its research. Exhaustive in its attention to details, Langford’s dedicated “reading” of “‘Photographs’ 1916–1945” is transformative. The few snippets of textual information available in the album – names, dates, backgrounds, signage, and a single newspaper clipping – are metamorphosed into a thorough and extremely touching account of the lives shared by two unmarried, motherless sisters who summered in Sainte-Adèle and enjoyed the occasional picnic in the countryside with relatives and friends.

It’s the oral “recitation,” however, that sets this study apart. True to her word, Langford reanimates the conversation meant to be inspired by the album, but suspended by time. Giving voice to the original compiler, the author stands in for her. As a faithful guide, she points to the images that would seem to have mattered most: Times, places, and faces repeat themselves, stages are set and reset, characters emerge and return. That Langford was touched by the affection and compassion between the sisters is wholly apparent. The kind and character of the language she uses to reprise their stories is equal to these expressions and inspires them in kind.

It bears repeating that this is a remarkable book.