[Winter 1996-1997]

Centre international d’art contemporain de Montréal

October 5–November 24, 1996

How about a crash course in the history of the female nude in photography? How about replacing the female models with Adam himself? That, in a nutshell, is what Montreal photographer Chuck Samuels’s Before the Camera is about. Presented as part of CIAC’s 11th edition of Les Cent Jours d’art contemporain de Montréal, Samuels’s twelve colour and black-and-white photographs are faithful reconstructions of portraits of nude women, many of them familiar, by modern masters, such as Edward Weston, Man Ray, and Ralph Gibson—with the striking exception that Samuels has positioned his own body “before the camera.”

Although Samuels goes so far as to replicate the dimensions of the original prints, he also goes the whole nine yards with his concept of deconstructive inversion. The actual taking of the photographs has been left, for the most part, to women. This information is made obvious by the labels that identify the images. For instance, in the photograph where one might expect to see Natassia Kinski’s curves rivalling those of the boa constrictor winding around her naked body and gets a reclining Chuck Samuels with snake instead, the label reads: “After Avedon,” 1991, with Nellie Dahan.

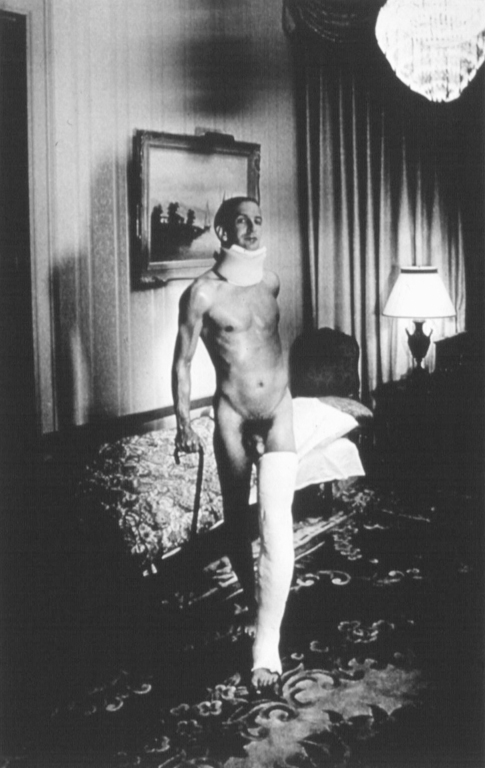

Clearly, Samuels’s photographs seek to heighten our awareness of representational voyeurism—more specifically, of how we have come to accept women’s bodies as objects of erotic consumption. Has he succeeded? Just imagine how you might feel looking at a portrait of a nude man leaning on a cane in an ostentatious living room staring down his nose at you, with a painted face, a neck brace, and polished toes protruding from a foot set into a cast that rides his right leg to his genitals (“After Newton,” 1991, with Sylvia Poirier). . . . Aroused? Not quite. At least not from a heterosexual viewpoint, plainly the main perspective at play in this exhibition, which proposes to undermine the long-standing tradition of objectification of the female body as practised by male photographers.

Although Samuels is not telling us anything we don’t already know, although his debt to feminist art theory and art practice of the late sixties and seventies is unmistakable, there is a satisfying efficiency in the way a simple gender inversion serves to make his point. Because a number of the images he parodies have been widely diffused, chances are that viewers will recollect at least one of the originals that are the objects of his travesty. Thus, viewers will be able to make the expected comparison and perhaps figure out what is so disturbing, or merely awkward—such as the naked man resting on his side and seen from the back, symbiotically basking in the innocence of the surrounding nature (“After Callahan,” 1990, with Cheryl Simon & Robert Milliken)—about these images that are all dressed up with nowhere to go.

Back to art history, whence, after all, Samuels is deriving his subject matter: he may be following the well-trodden path of women artists who question the politics of gender with regard to representational conventions, but how many male artists, one wonders, have previously addressed the issue? If absolute identification with the Other is just not possible, no matter how “uncomfortable” (in his words) the poses, at least Samuels has tried. However, since art is said to be asexual, let’s leave it at the effective simplicity with which Before the Camera offsets a salient aspect of our cultural legacy. To the point and explicitly visual; a rare and happy instance of “artistic social commentary.”