[Summer 2007]

Mining the aesthetic territory of the apocalyptic sublime, and addressing themes of loss, elegy, and memorialization. Black Maps, David Maisel’s aerial-photography project, captures the world of nature as it is being undone as a result of extensive intervention in the environment.

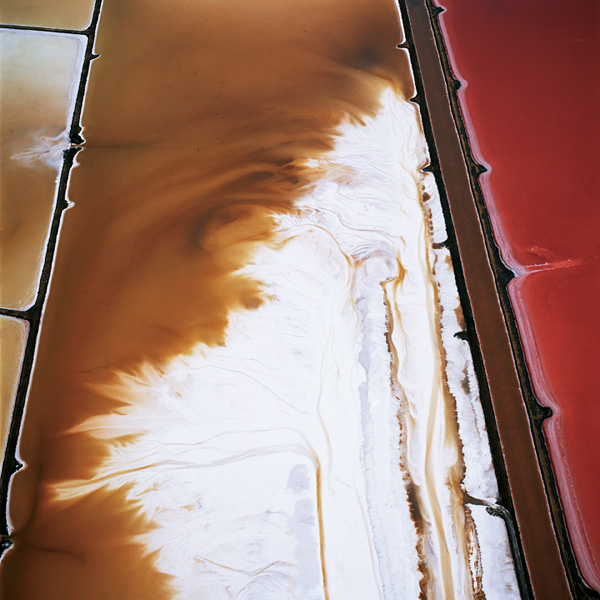

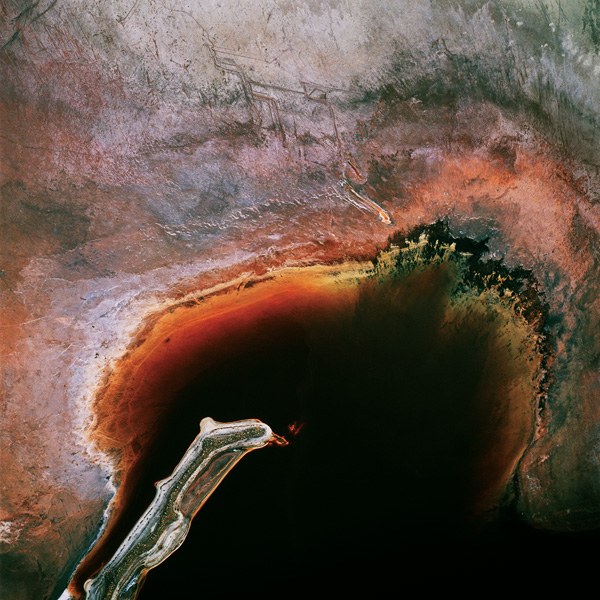

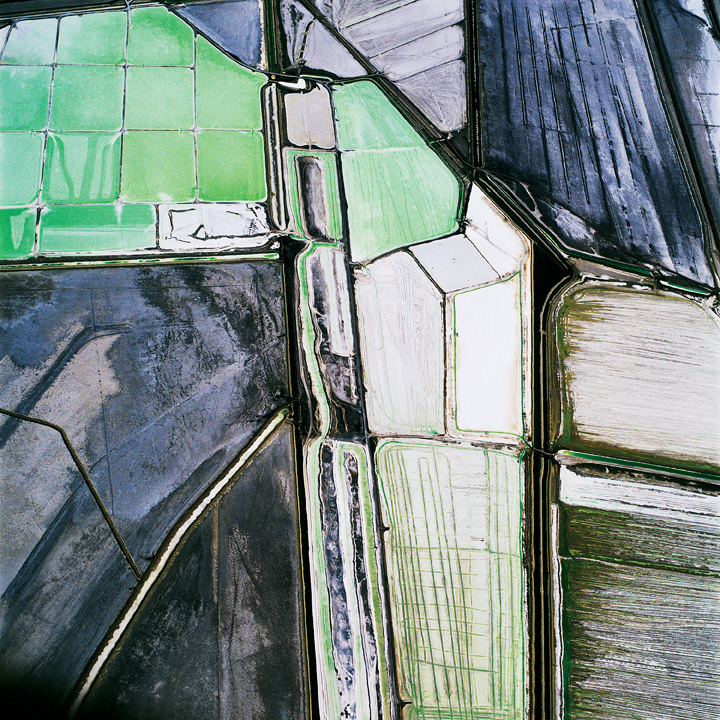

His images of these environmentally damaged sites, where the natural order has been eradicated, are both spectacular and horrifying. The Lake Project (2001–03) comprised images made near Owens Lake in California, which was drained and depleted in order to bring water to the desert city of Los Angeles, and which became an enormous environmental disaster in the process. Terminal Mirage (2003–05) uses aerial images made at the site of the Great Salt Lake as a means to explore both abstraction and, as the curator Anne Tucker has written about this series, “the disturbingly engaging duality between beauty and repulsion.”

The scale of Maisel’s prints, at up to 48 x 96 inches, serves to convey the seemingly limitless aspect of the sites from which they are made. The forms of environmental disquiet and degradation function on a metaphorical level, and the aerial perspective enables one to experience the landscape like a vast map of its undoing.

John K. Grande: The performance artist Tadeusz Kantor once wrote, referring to painting, “Space which retracts violently condenses form to dimensions of molecules to the limits of the Impossible. In this dreadful moment the speed of making decisions and of interventions constantly grazes risk.” Some of your aerial photographs are as abstract as a Richard Diebenkorn painting, beautiful and with an aesthetic that simply manifests nature’s own patterns, forms, encroachments, and there is that dynamic of space, and of speed, a macrocosm envisioned as if it were a fragment of a larger body perhaps.

David Maisel: The quote by Tadeusz Kantor links the body to the act of painting, and to being located within the space of painting itself. Photographing from the air is like that, exactly: I become a kind of disembodied eye, floating in a space-time continuum. Aerial photography interests me not as a method per se, but as a way to see the otherwise unusable and unimaginable, and as a way in which time and space can get strung together. From a moving plane or helicopter, naturally, I am never in the same place twice, so no image can be repeated – it is a stream of images and possible framings that is not unlike the stream of consciousness itself. Motion gets dissected and reanimated. It is kind of like an altered state – leaning out the window of a small plane, or leaning out the doorway of a helicopter, with the wind rushing, constant motion and sound, looking through the viewfinder of a camera, with the horizon obscured.

At many of the sites that I choose to photograph, there is a sense of the landscape as a body inflicted by various traumatic events. This is perhaps most clearly felt at Owens Lake, the site of The Lake Project. I was editing film from my first aerial shoot there when the Twin Towers were destroyed on 9–11. For me, the blood-red waters remaining in Owens Lake were, from that point forward’ linked to this moment in contemporary society, when thousands of human bodies had just been destroyed in a moment.

In The Lake Project, there is also the aspect of seeing the landscape photograph as a kind of autopsy. After I had been making aerial images at Owens Lake for several years, I realized that this alien landscape was sort of an analogue for my mother’s death – she had died during open-heart surgery after a routine procedure went awry. Despite, or because of, my conscious decisions as an artist interested in the environmental disaster being told through the story of Owens Lake, I was, unintentionally perhaps, processing her death and my own grief by making these images.

JKG: Do you intentionally set out to find forms, textures, colours, things that exist, that awaken a sense of something personal, but from the theatre of the world that is our Earth – so surprising in that it surpasses any art we would set out to create, and yet finds its parallels in our art, for art surpasses the informational, the didactic.

DM: Yes, I suppose that I do respond to certain kinds of visual splendours. I wouldn’t call it beauty, exactly, but rather a sense of dislocation – the unfamiliar, the threatening, the sense of beauty and terror combined – I suppose it is “the sublime,” really.

When I was in my twenties I was struck by a deep, obsessive desire to photograph copper mines. I spent hours poring over aeronautical maps and obscure mining publications, charting a way out of wherever I was. I took to the air, again and again, photographing from a small plane the display of copper-hued earth splayed out beneath me, in mines in Montana, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona. It seemed that in the repetitive acts of research and circling over these sites and exposing frame after frame of film, I absorbed the copper into my skin, into my blood. Copper gave me a reason; it posed me a challenge; it compelled me to act. Copper offered me a process of alchemical transmutation not unlike metallurgy itself, by which my own identity as an artist was forged.

All of the aerial images from Black Maps capture a wide-scale intervention by humanity in the landscape. From the aerial perspective I occupy, the views that I see of these zones, where human activity has replaced the natural order, are both beautiful and horrifying. But, there is also contained in these sites an ineffable sense that they correspond to interior psychological states. So, rendering the environmental impact of these zones in a deadpan, clinical, or didactic way has not interested me. I experience these tailings ponds and leaching fields as sites of horror that were reflective of something absolutely intrinsic to human nature. I am not attempting to make literal records of environmental degradation so much as I am seeking to reveal the landscape as an archetypal space of destruction and ruin that mirrors the darker corners of our consciousness.

JKG: How did you choose to get into aerial topographical photography of water, mountains, the land? These works suggest a growing consciousness or awareness that photography can extend to or encourage among its audience.

DM: Working from the air allows me to see things that are secret. The deconstructed landscapes of strip mines, cyanide leaching fields, tailings ponds, and drained lake beds seem to me to be the contemplative gardens of our time; they are like subterranean dream worlds demanding to be brought into the light of day. I think of my pictures not simply as documents of these blighted sites, but as poetic renderings that might somehow reflect back the human psyche that made them.

I first experienced aerial photography when, as an undergraduate at Princeton University in the mid-1980s, I accompanied my photography instructor, Emmet Gowin, on a photographic expedition to the volcano Mount St. Helens. The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens was the deadliest and most destructive volcanic event in the history of the United States. St. Helens released energy equivalent to 350 megatons of dynamite, or 27,000 atomic blasts over Hiroshima, or seven times more than the strongest atomic bomb ever built and tested. What struck me at the time was the sense that the clear-cutting of forests by the timber industry was a destructive force on a par with that of the volcano; it seemed absolutely biblical in scale.

DM: Years ago, when I began my project on open-pit mining in the American West, I was photographing exclusively in black and white. But the colours at many of these sites were really so seductively gorgeous and so awful, simultaneously. I realized that their meaning and potency were transmitted through that unearthly, magnificent colour, and so I began to consciously work with that palette. The aerial view and the scale of these prints (up to 48″ x 48″) and the colour combine to heighten our sense of what it is we are witnessing visually.

The themes of seduction and betrayal inform my thinking and my work in a number of ways. We’re constantly seduced in our daily lives by whatever it is that is new, shiny, the next consumer object to be desired – the suv, the iPod, the widescreen tv. And I include myself here, quite readily. And I think we’re betrayed by these desires, and these objects, because they can’t, they don’t, really satisfy us existentially, they just create more longing. Simultaneously, we betray the environment as we thresh through it and use it up in a vacant effort to fill those endless longings that cannot be quelled. We are complicit in the destruction of these zones. The seduction yields the betrayal.

JKG: When you first photographed Smithson’s Spiral Jetty at Great Salt Lake in Utah and captured the environmental changes taking place, ongoing since Smithson originally made the piece, you must have sensed that you were capturing change in process, a slow change that few of us are aware of as we go about our daily lives.

DM: I look at landscape from a conceptual point of view – it has fuelled my pervading interest in the work of Robert Smithson and Gordon Matta-Clark, two artists who explored the undoing of things, the endgame, the absent, the void. I’m drawn to aspects of the sublime, and to a certain kind of visceral horror, and in a sense I am using my landscape imagery in order to get to that feeling, as much as or even more than I am documenting a specific open-pit mine or cyanide leaching field or clear-cut forest (and I’ll readily admit that my work may not hold up very well from a documentary standpoint). In Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, the landscape is a sort of existential landscape, a place that Becket might have invented. There is a sense of being threatened, but also of being more alive.

In Terminal Mirage, a body of work inspired by Smithson’s writings on the Great Salt Lake, I’ve sought out gridded sites around the periphery of the lake – among the thousands of acres of evaporation ponds, amidst the military zone of the Tooele Army Depot that houses and burns expired chemical weapons. There is no scale reference in the images, and the “facts” of the photographs become instead a series of dizzying tropes. Terminal Mirage is also concerned with the limits of rational mapping. The grids of evaporation ponds are a kind of architecture that transgresses, a labyrinth laid endlessly over the surface of the lake and its shoreline. The project Terminal Mirage gets its name from the fact that the Great Salt Lake is, indeed, a terminal lake, with no natural outlets. The claustrophobic, no-exit, existentialist aspect of this fact sparked my curiosity. And the word “mirage” seems to describe the entire hallucinatory quality of the expanse of the Great Salt Lake, the unflinching light that illuminates it and that is reflected from its surface, and the manner in which this body of work questions the nature of sight and perception.

JKG: There is a photographic tradition of capturing the American frontier that extends back into the nineteenth century, established by Carleton Watkins and William Henry Jackson, for instance. Our frontier is now one that involves transgression, transformation, and disruption of environments. Do you believe photography is linked to its own traditions, or does it go beyond the traditions that it has evolved out of?

DM: I’m motivated by the notion of discovering and revealing sites that might otherwise remain unknown or unseen. In this way, there is a continuity between the nineteenth-century exploratory photographers and my work. However, my photographs are intended to be reflective of some sort of internal psychological state as much as they are documents of a particular site. And, I consider myself a visual artist first and foremost – as opposed, perhaps, to a photojournalist or a documentarian. I’m most interested in making images that have a kind of depth-charge, that have a certain poetic or metaphoric impact visually.

JKG: Ultimately your work exposes the consciousness inherent to all human activity, and it does so by documenting landscapes in transition, much as the New Topographics photographers did, but with a less antagonistic approach, as if to say, the situation exists, let’s be aware of it, and start to work at improving the land, with the distance and wisdom that we obtain from knowledge.

DM: I think that is a generous view. I recall feeling when I first viewed works from the work dubbed “New Topographics” that there was a kind of tonelessness to many of the images. Now, though, when I look at those photographs, I feel a kind of silent scream building in them.

I don’t think that my work is positing any happy endings! I don’t really think that we, the human race, have much of a place left on this planet. If you think about it from a geological perspective (as Smithson might have), we are just a flicker of light that vanishes almost instantly. So, perhaps we might obtain some knowledge or wisdom about land use and abuse from my work (or that of other photographers), though I think we humans and our fragile little history have a place in the cosmos, but perhaps it is a smaller place than we might like to imagine. We still tend to think in a geocentric way – doesn’t the universe revolve around us? – and the answer is, no, it does not.

JKG: The Lake Project pieces are al-encompassing overviews and we read them almost as if they were parts of an organism. These macro-viewed images resemble the micro-view subjects we might see in the cameras now used in medicine. When we are informed of the actual reasons for the colourations and textures – pollution, algae growth, etc. – the subject that we potentially read as beautiful, for all its aesthetic and transparent beauty, becomes unsettling, for there is a basic antagonism between our reading of the work as a visual phenomenon and our knowledge of the somewhat less measurable, invisible causes for these effects. Can you comment?

DM: Owens Lake, the locus of the Lake Project images, is the site of a former 150-square-mile lake on the east side of the Sierra Mountains. If you know the movie Chinatown, then you are familiar with the history of the demise of this lake. Beginning in 1913, the Owens River was diverted into the Owens Valley Aqueduct, to bring water to the fledgling desert city of Los Angeles. By 1926, the lake was essentially deconstructed, leaving vast, exposed mineral deposits and salt flats. Once the water was gone, high winds that sweep through the valley would dislodge microscopic particles from the dry lakebed, creating carcinogenic dust storms. In fact, the lakebed has become the highest source of particulate-matter pollution in the United States, emitting 300,000 tons of arsenic, cadmium, chromium, chlorine, and sulphur a year. The concentration of minerals in what little water remains in Owens Lake is so artificially high that blooms of microscopic bacterial organisms result, staining the remaining water a deep, bloody red.

While I was engaged with this project in 2001–02, the epa and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, urged on by the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District, began transforming the region yet again. In an effort to reduce the toxic dust storms, a large area of the lakebed has been turned into a flood zone. It is infinitely complex, like the Lost City of Atlantis rising from the floor of the lakebed. In fact, after I’d completed this project, I got down onto the surface of the lakebed, and was able to gain access to the control room centre that maintains and measures the salinity and relative moisture from the 60,000 miles of irrigation drip tubing that criss-crosses the flood zone. There, on their computer screens, were these familiar shapes of the flood zone that they image with remote aerial photography and satellite mapping. Everything in this landscape is mediated – it is the most replicant landscape I can imagine.

The antagonism you sense – between the surface beauty of the images and the disturbing content that underlies them – is one of the reasons the pictures are compelling. They don’t give answers, per se; they don’t tell you what to think or feel. In this regard, perhaps they work more like contemporary painting than photography. I’m coming to the somewhat terrifying conclusion, rather belatedly perhaps, that my work is really about representations of modern-day, man-made holocausts. Of course, representations of holocaust and apocalypse have been part of the history of art for centuries. What distinguishes this age from earlier artistic renderings is that the means for accomplishing the destruction of the self and the world is no longer in the realm of prophetic mythology. The human species has been technologically capable of destroying itself for decades.

David Maisel (New York, 1961) is a photographer and visual artist based in the San Francisco Bay area. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Opsis Foundation. His artwork is represented in major public and private collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Maisel’s photographs have been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions in the United States, Canada, and Europe. His first book, The Lake Project, was published by Nazraeli Press in 2004, and was selected as one of the top 25 photography books of that year by critic Vince Aletti. Maisel’s second book, Oblivion, was published by Nazraeli Press in the fall of 2006.

John K. Grande is the author of Balance: Art and Nature (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1994 and 2004), Intertwining: Landscape, Technology, Issues, Artists (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1998), and Art Nature Dialogues: Interviews with Environmental Artists (Albany: SUNY Press, 2005). His latest book, Dialogues in Diversity: Art from Marginal to Mainstream, has just been published by Pari Publishing in Italy.