[Winter 2006-2007]

by John K. Grande

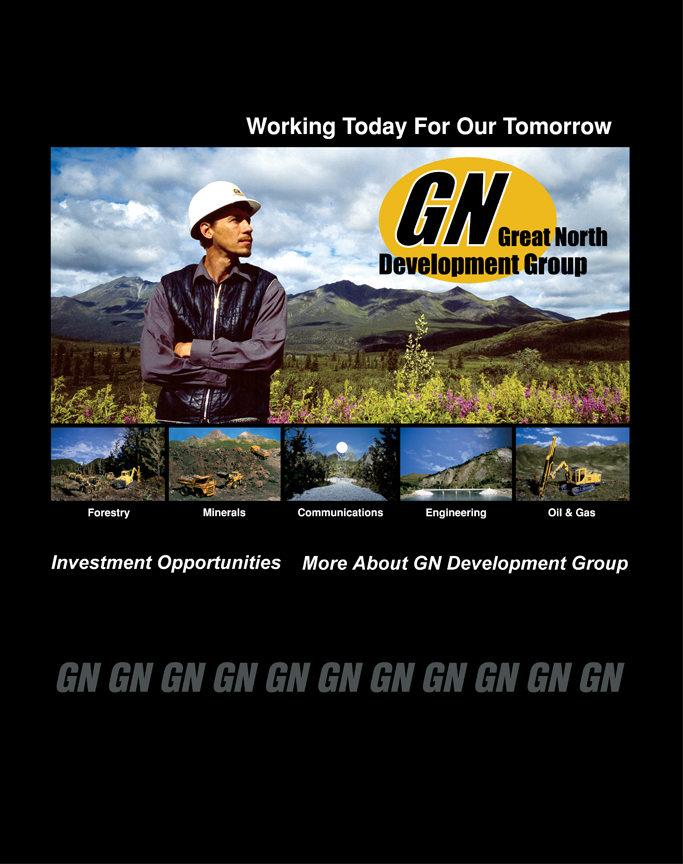

Multidisciplinary artist Mike Yuhasz’s Great North Development Group project explores the way that we conceive of and relate to land in today’s complex world. Great North Development thus becomes testament to the spirit of our era as envisioned by an artist who actually lives in the north – Dawson City, the Yukon, to be more specific. Yuhasz’s confected, prearranged, set-up, and situational photographic and informational material carries contradictory and duplicitous messages about the consumer ethos. The project is as much about our collective perception, understanding, and potential exploitation of land as territory as it is about the orchestration of visual information and the sophistication (or lack thereof) of presentational frameworks in today’s society.

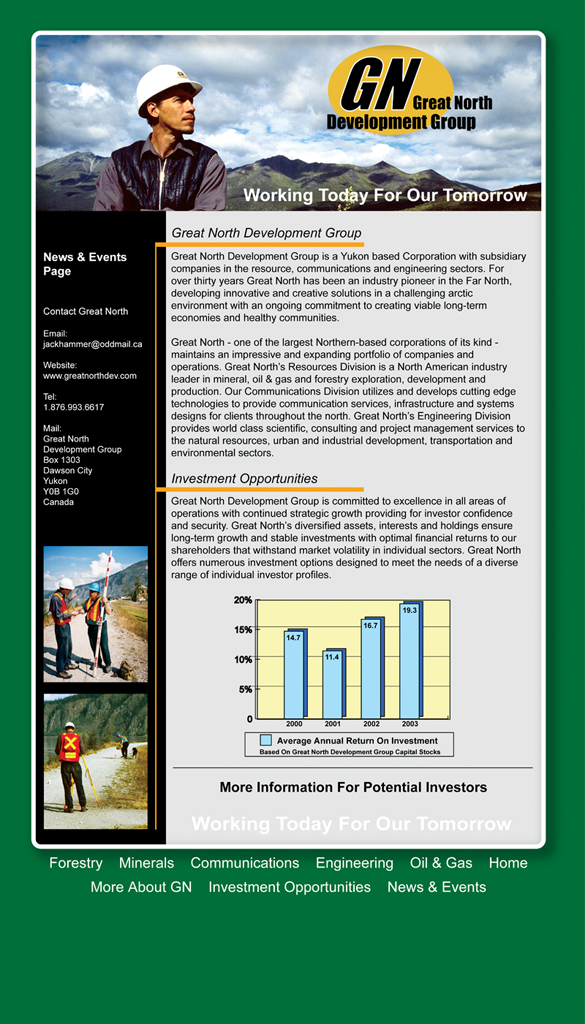

On Yuhasz’s Web site, we learn that “Great North Development Group is a Yukon based Corporation with subsidiary companies in the resource, communications and engineering sectors. For over thirty years Great North has been an industry pioneer in the Far North, developing innovative and creative solutions in a challenging arctic environment with an ongoing commitment to creating viable long-term economies and healthy communities.” Furthermore, “Great North Development Group is committed to excellence in all areas of operations with continued strategic growth providing for investor confidence and security.” The logos and charts are edifying, as are the intense photographs of beaming CEOs with the Klondike Kickers and of “trade show attendees” staring into 3D viewers to see their eventual investment ideas realized or perusing Web sites on a computer screen. Everything is presented as goodness. There is no evil in these innocent investors. They could be you or me! And distance and disconnect are the primordial technologically correct keys to it all!

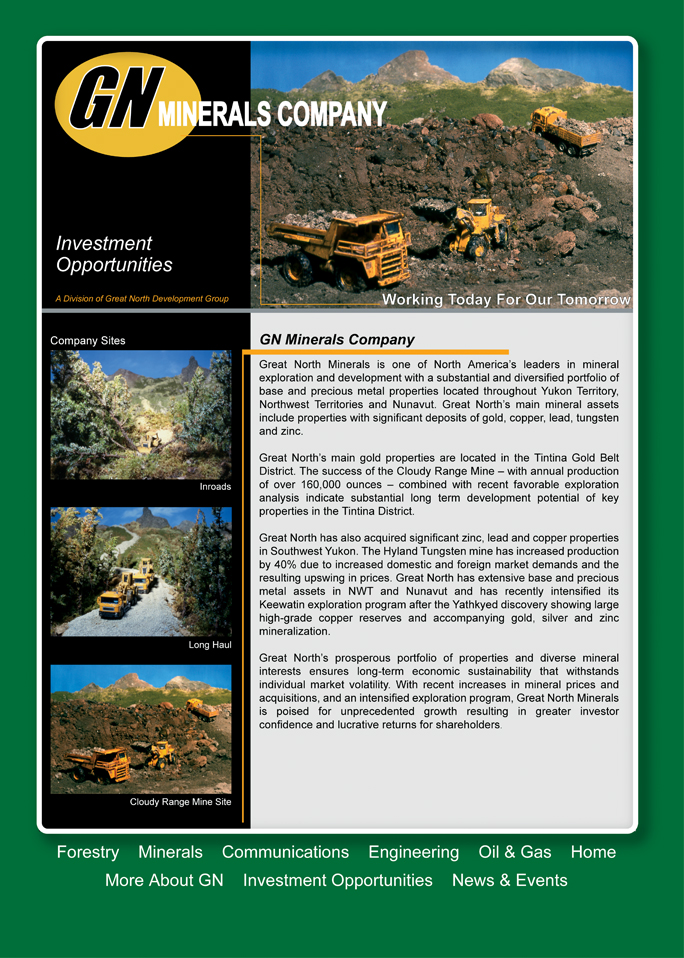

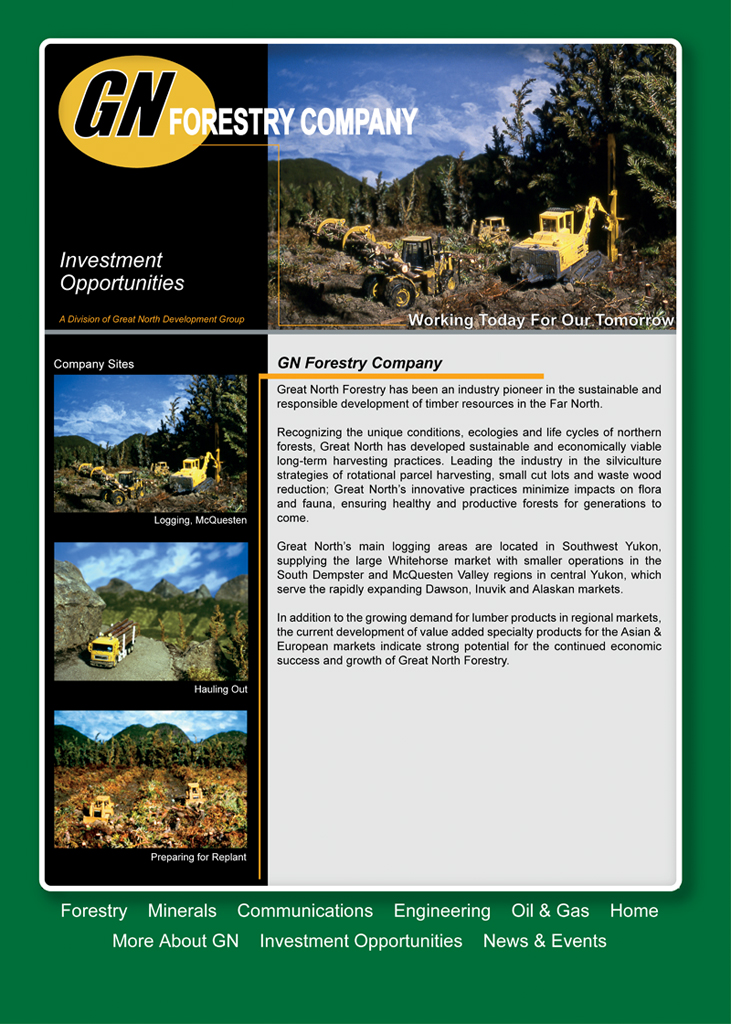

Humour and fatalistic abandon pervade Yuhasz’s approach, but there is some truth hidden under the double entendre of his confabulated Web-based genre of artmaking (the visual documentation as an action seems, with Yuhasz, closer to performance art than to formal or conceptual art). The Web site categories of Great North Development evolved into a fictional construct that actually resembles the real thing. Click on the sidebars of Yuhasz’s Web site – Forestry, Communications, Minerals, Engineering, or Oil & Gas – and you can participate in the bacchanal that is corporate greed. Greed has a smile. It even wears a worker’s hard hat, so sympathetic is this deadly sin to the ordinary working citizen’s concerns, but beneath the disguise, this CEO (a.k.a. Mike Yuhasz the multimedia artist) is still measuring the profits and costs, and is investing elsewhere. Great North Development is a construct that parallels the way that we in the West have come to view the world around us. It is all about the disconnect between reality and fiction, and the way that potential wealth is presented as a simple series of steps, as if nature did not matter at all. This may be the case worldwide at present, as anyone can see with the latest oil-and-gas development in northern Norway or mineral exploitation in Brazil or open-pit mines in George Bush’s America, but we would be holier than thou if we Canadians (hewers of wood and haulers of water in the old caricature) did not admit that we were whole hog into the same planetary disfigurement and landscape destruction as the rest of the motley crew of First, Second, and Third World nations on earth. Ethics is probably relegated to a cosmetics bag at this point in time!

What an homage to today’s planetary malaise. Forget the products. What about the resources? It is all cleverly captured in the root-point wilderness setting – even orchestrated with a communications edge that is also part of Mike Yuhasz’s project realization. There are no Natives in this new North; land use is what it’s all about. Land disuse is also what it’s about. Yuhasz has constructed an elaborate web of truthful looking untruths, or vice versa – take your pick!

And there is that Orwellian Great North Development slogan, “Working Today for Our Tomorrow”! Utter a word of truth in this artistic project and it’s “Minus Minus Good,” in the land of Newspeak. “Working Today for Our Tomorrow” appears and reappears on the Great North Development Web site, echoing investor confidence in the Whole Earth second or third scenario. The artist’s corporate look is an artform in and of itself, and it is there in the promo photos. There is a distancing, a generalized informational tone to each image. The photographs could have been taken in virtually any landscape on the planet. They look like maquettes rather than the real thing. Clues to this are the toy-like machines and the scale, something that enhances the concept-driven nature of this project, and real world development. No alternative is presented to the parody of development in Yuhasz’s proto-propaganda.

The Web site even includes an “events page” to further prove good corporate citizenship in a largely Aboriginal land. We learn that Great North participated in the 18th Annual Dawson City International Gold Show, and that CEO Mike Yuhasz “enjoyed the opportunity to participate and support this very important community and industry event.” Words such as “awareness” and “reconnect” and a lengthy line of old friends, business partners and associates, industry contacts, and new investors suggest that there are no ordinary people at all. Everybody’s part of the corporate body here, and nobody has any awareness of the planetary body. Incidentally, Great North commends the Dawson City Chamber of Commerce on another great Gold Show.

Yuhasz’s project replicates a reality not unlike the one that Guy Debord outlines in Society of the Spectacle (1967). Even as we “work” we seem to be “playing,” and to consume is the ultimate, or penultimate, prototype for the dedicated, properly placed worker. Yuhasz confirms Debord’s prediction that for contemporary society all that was once directly lived experience becomes replaced by mere representation. As Debord suggested and Yuhasz suggests, contemporary social life is part of a process involving a decline from being into owning, and having moves into mere appearance or the look of things.

Great North Development, as a suggestive phenomenon, has a mystique that is typically presented with a positive spin in most mainstream media. This usually involves an institutionalization of development as a socially correct principle, and the public is given a narrow view of its effects. The notion that social mores and social life have been replaced by mere image, as suggested by the investors staring into viewfinders to see their potential value, confirms Debord’s belief that there will be a historical point in time when the commodity completes its absolute colonization of social life. We are there, it seems, in 2006. What Debord and others failed to comprehend or deal with was the physical effect of commodification on the ecosystem, on resources, and ultimately on human civilization. These effects continue to be unseen, to have no single responsible agent or force generating their effects. Rather, they form an ongoing process wherein the human condition affirms itself, regardless of nature or of socially and ecologically responsible “rational” behaviour.

It is an invisible evil that we are dealing with: no one is to blame. As Babylon’s empire expands, questions remain: What resources will be left? Has all collective and ancestral memory – memory of place, memory of the past, memory of nature – been erased? Post-humans, beware! Here it all is, for nobody to share. Theme parks now look like development land and vice versa. Truth, it seems, is as malleable as a piece of clay. Note the cleverly concealed language of the developer in the phrases from this hyper-designated and logo-ized land of plenty:

Great North Forestry has been an industry pioneer in the sustainable and responsible development of timber resources in the Far North. . . . Recognizing the unique conditions, ecologies and life cycles of northern forests, Great North has developed sustainable and economically viable long-term harvesting practices. Leading the industry in the silviculture strategies of rotational parcel harvesting, small cut lots and waste wood reduction; Great North’s innovative practices minimize impacts on flora and fauna, ensuring healthy and productive forests for generations to come.

Landscape becomes a perceptual condition, and in the New World, it plays on and with the absolute plastic fantastic character of corporate identity and all that it entails. With his Great North Development project, Yuhasz does not necessarily encourage an understanding of our links to nature, but he successfully explores the parameters of contemporary media and corporate culture. In so doing, he subtly redefines and raises questions about the artist’s role in this era of social and economic transition.

Mike Yuhasz lives and works in Dawson City, Yukon. His multi-disciplinary practice provokes a rethinking of familiar romantic images of the North, and explores complexities and contradictions in our relationship to the land. Yuhasz’s recent work was shown at Gallery 44 Centre for Contemporary Photography in Toronto, the Edmonton Art Gallery, the Yukon Arts Centre Gallery in Whitehorse, and the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg. It was also part of Image & Imagination: Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal 2005.

John K. Grande has published numerous catalogue essays on selected artists and has taught art history at Bishops University. He co-authored Nils-Udo: Art with Nature (Wienand Verlag, Koln, Germany 2000), Nature the End of Art: Alan Sonfist Landscapes (2004) and Le mouvement intuitif: Patrick Dougherty & Adrian Maryniak (Atelier 340, Bruxelles, 2004). Grande’s latest book, Art Nature Dialogues: Interviews with Environmental Artists, published by SUNY Press, New York, investigates artists’ visions of working with nature in today’s world.