[Spring-Summer 2014]

Martha Langford is the research chair and director of the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art and a professor of art history at Concordia University in Montreal. Her books on photography include Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums (2001); Scissors, Paper, Stone: Expressions of Memory in Contemporary Photographic Art (2007); A Cold War Tourist and His Camera, co-written with John Langford (2011); and an edited collection, Image & Imagination (Mois de la Photo à Montréal, 2005), all published by McGill-Queen’s University Press. In March 2014, the Art Canada Institute released Langford’s online art book Michael Snow: Life and Work/Sa vie et son oeuvre. speakingofphotography.concordia.ca

An Interview by Jacques Doyon

JD: Universities and museums regularly offer colloquiums and lecture series on art, but very few of these concern photography specifically. The only one I can think of is the Kodak Lecture Series at Ryerson in Toronto, which is in its thirty-eighth year. That series must have served as a model of some sort for you. What was the context for organizing Speaking of Photography at Concordia, and what are your goals?

ML: The series was born in conversation with Robert Graham, a very good friend, a photographic scholar, and a generous supporter of ideas in the arts. I had recently started teaching at Concordia University, where I was hoping to develop a very strong photographic program. Robert offered to support a lecture series on photography, without imposing any conditions, and made it clear that he would continue to do so for as long as I wanted. This was perfect on so many levels; freedom is always nice, but a reliable contribution allows one to build connections with potential speakers and, most importantly, to grow an audience. Initially, I was thinking only of our students. I did my undergraduate degree at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design – here I’m referring to a very exciting time at NSCAD (I graduated in 1975), when the visiting artist program was justly famous – and I wanted to give my students time with some of the scholars who were influencing their work. This would be both inspiring and instructive.

The Kodak Lecture Series is a great achievement, but its primary focus on practitioners makes it a very different project. I never thought of it as a model, except possibly in one respect. When I spoke there myself, in 1992, I received the most generous introduction by a great photographer and worker for the field, Phil Bergerson. I floated to the podium. And this taught me that there is a way to honour speakers’ career achievements and their humanity. I want Speaking of Photography to have a very warm atmosphere, even when there is debate – especially then.

The audience’s engagement gives me a great deal of satisfaction and teaches me a lot about how people respond to images and use them as platforms for all kinds of investigations and connections.

JD: Can you talk about your speakers and describe the scope of the topics that they have addressed? Are there some recurring themes or is there a preconceived structure to the series each year?

Or are the lectures inspired by current research, publications, or visits to Montreal by international speakers? Are there some highlights – some lectures that you’re particularly proud of or that have had a particular impact?

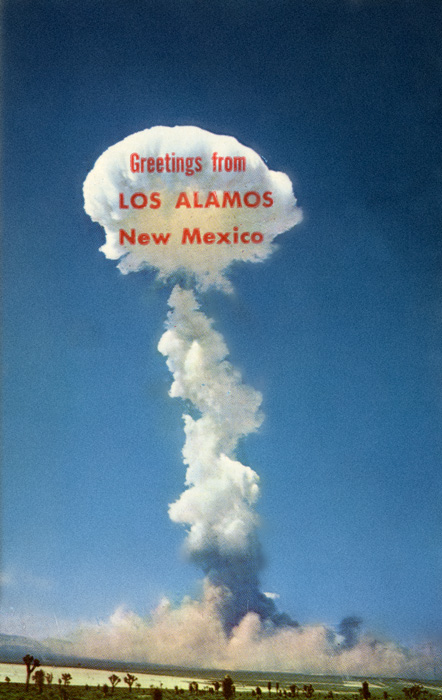

ML: There has been quite an emphasis on vernacular photography and print culture – postcards, magazines, and illustrated newspapers. We have heard about Indian studio photography, spirit photography, and war photography. Much of this reflects the interests of my doctoral students, who are writing a photographic history that’s very different from the European or American standard. If you look at the first year – Aurèle Parisien’s initiative in creating a website/archive allows one to do that – both stature and variety are there from the beginning. I was assigning Mary Warner Marien’s history to my undergraduate students – suddenly she was standing there, talking about pre- and post-photographic realisms. Marianne Hirsch, a companion in memory studies, talked about a street photograph of her parents (I am thinking about that lecture again as I write about a picture of my own mother). All my students were reading Geoffrey Batchen on vernacular photography. At Speaking of Photography, he gave a wonderful lecture on memory and tactility. The next day, he gave a graduate seminar, taking the opportunity to question the whole category of “the vernacular.” This was pretty dazzling, and also a little disorienting for his fans. Also in the first year, Rosemary Donegan’s lecture drew attention to Canadian industrial photography within the visual culture of labour. John O’Brian’s lecture and seminar on nuclear postcards opened the gates to everyday photographic experience – another way of seeing the banality of evil, funny and very troubling at the same time.

Looking back for the purposes of this interview, even I am surprised at the interdisciplinary breadth. Some of the best work is coming from scholars who are unclassifiable – shall we call Elizabeth Edwards a photographic historian or a visual anthropologist? Is Joan Schwartz doing history or geography? These combinations and cross-pollinations are nicely integrated in texts, but a lecture lets us see some of the joints in the argument, making for an exciting and memorable question period when different interests begin to pry the building blocks apart.

Photographic studies has changed dramatically over the last twenty years. Still, it would be possible to program much more conservatively, chronologically or by movement; scholars, especially museum curators, still think in these terms. But the series seems to require something innovative. I was very amused by Bill Ewing’s response to the invitation. Here is an international curator and editor who has worked on established photographic genres – portraiture, the body – and on famous photographers – Arnold Newman, Edward Steichen. He wanted to give a lecture on the figure of a photographer as constructed by advertising – an exemplary phantasm, in other words. This example reminds me to say something very important about the series, which explains why I do not claim to “curate” it. Just as Robert Graham gave me carte blanche to organize the series, the invited speakers are encouraged to do what they like. Some are naturally guided by my enthusiasm: Tony Lee, for example. I had fallen in love with his book A Shoemaker’s Story. And we have had a few book launches, whose theme should be obvious, but here again, scholars are always prospecting and this is a good forum for it. When Carol Payne spoke about her new book, The Official Picture, she ended her lecture with thoughts on where the writing of Canadian photographic history might be headed. I am very grateful to the speakers and sponsors for their generosity. To make this point, I might refer to those who travelled great distances. But generosity takes many forms. Vincent Lavoie arrived via Métro from the Université du Québec à Montréal to elaborate his ideas on forensic photography. Some of this work had been previewed in Ciel variable; he pushed it further. The series is doing its best work when it fosters that kind of energy and community.

JD: What about the impact your series has had? What has been its reach in terms of audience? Its effects on your students’ research in photographic studies? Its eventual impact on photographers?

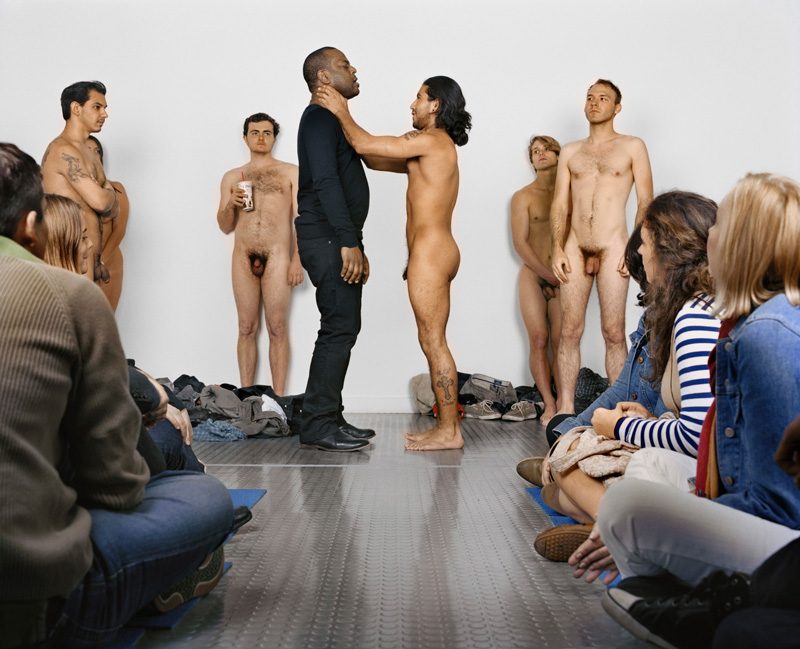

ML: The series has settled into many people’s lives; they look forward to the lectures. I look forward to question period, which gets better every year. The audience’s engagement gives me a great deal of satisfaction and teaches me a lot about how people respond to images and use them as platforms for all kinds of investigations and connections. As an exhibition curator, I never felt this broadly informed about levels of understanding and effect. Deborah Willis’s lecture two years ago, “Posing Beauty in African and African American Culture,” drew widely from the black community and thrilled her audience – students were running to tear down posters so that she could autograph them. That’s Deb, and that doesn’t happen at every event. Sometimes people leave quietly to have a drink and a think. Photographers do not make up the majority of the audience; they come when a curator is speaking – that’s understandable. I think that they should come more often, because the atmosphere can sometimes be electric, and it is always reassuring about the importance of what we do with and about images.

JD: You’ve just completed your 2013–14 series, the seventh one. Can you give us a preview of who will be invited next year? How do you envision the future of Speaking of Photography? Do you have any particular goal in mind for its development?

ML: The only preview I can give is that the series is continuing. I want to do two things. The first is to enlarge the place of contemporary photography in the program – I mean, the new. Paul Wombell and Lucy Soutter showed us recent phenomena and speculated on the future. Sometimes these ideas are still coming together, but their rawness can be provocative and productive for artists. Still more transdisciplinary approaches would be good; I am increasingly identifying with photographic studies, and I have found that the impact of the series is greater when we think in those terms. I can’t name names for 2014–15. I still hope that a certain visual anthropologist will answer my mail. We shall see.

Jacques Doyon has been the editor-in-chief and director of Ciel variable since January 2000.