[Spring-Summer 2012]

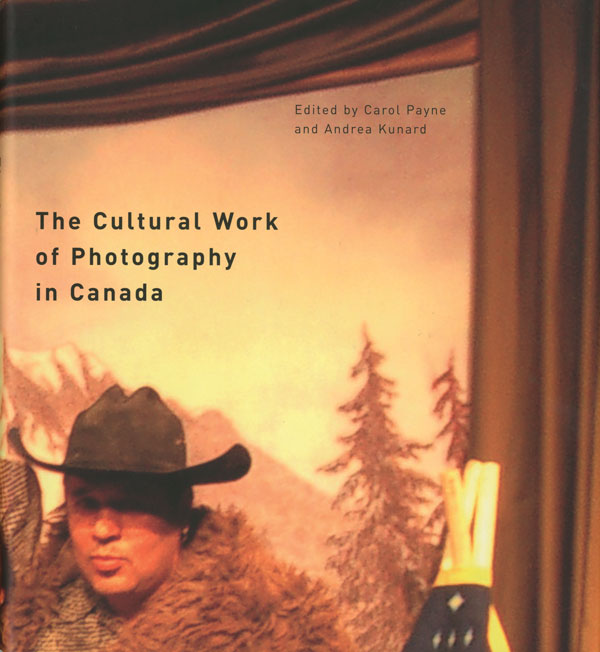

The Cultural Work of Photography in Canada

Ed. Carol Payne and Andrea Kunard. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2011

This Is Not a History of Canadian Photography. Less a history of Canadian photography, more a Canadian history told through photography, The Cultural Work of Photography in Canada considers how photographic representation is deployed to shape identity. Co-edited by Carleton University professor Carol Payne and Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography curator Andrea Kunard, the book represents the most extensive contribution to scholarship on Canadian photography in more than twenty years and may be one of the most important. Including reflections on historical and contemporary practices and contributions by archivists, art historians, artists, curators and artist-curators, the collection of essays brings together what have otherwise been distinct disciplinary practices and so gives a comprehensive shape to the field of photographic studies in Canada for the first time.

The editors take pains to underscore that this is not a history of Canadian photography. Indeed, what distinguishes this compilation of writing on Canadian photographic practice from most previous incarnations is that it proceeds from the understanding that history, like photography, shapes its subjects through complex representational means. The Canadian-ness of visual expression is not given in advance, an extrusion of some essence to be discerned in the photograph, but a value produced in discourse, photographic and otherwise. Indeed, in both content and form the book involves a highly self-reflexive interrogation of history making. Framed by reflection on historical practice itself, the introductory and concluding chapters situate the publication within a history of writing on Canadian photography.

A distinct historical narrative can be discerned in the book’s principal focus on Canada’s colonial past. Although not presented as the singular story of Canadian history, the majority of the contributions here chronicle the political shaping of Canadian identity as enacted through and in photographic representations of Indigenous peoples, from the ethnographic projects commissioned during the colonialist era to the critical rejoinders of Aboriginal photographic artists in the present day. Indeed, the collection is framed by a dialogue around the role of photographic representation in the production of the “imaginary Indian.” Joan M. Schwartz’s essay on German photojournalist Felix Man’s 1933 picture story of Canada inaugurates the first part, Visual Imaginings, and also builds the conceptual foundation for the book as a whole. Following Benedict Anderson and Edward Said’s concept of “imaginary geographies” – a relationship with geography that is more imaginary than real – Schwartz speculates that Man’s preference for the Canadian wilderness over depression-era urban Canada may have been determined by an imaginary construction of the New World derived from the Wild West adventure stories popular in Germany when Man was a boy. That these representations were likely modelled on other, equally contrived representations of the wilderness circulating in Europe at the same time – James Fennimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking tales, William Notman’s portrait Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill, and, of course, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West travelling show among them – makes Man’s portrayal of Native North Americans captured at Banff’s Indian Days tourist spectacle a highly mediated and thoroughly fictionalized representation.

Given that the book is organized dialogically, the first section and the book itself conclude with contributions considering oppositional situations. Artist and scholar Sherry Farrell Racette’s “Returning the Fire, Pointing the Canon: Aboriginal Photography as Resistance” ends the first section of the book with an impressive historical survey of photographic practice conducted within Indigenous communities by Indigenous photographers. Indigenous photography is distinguished from “the photo colonialism” of settler and scientific practice by the manner in which the photographers approached their subjects: as individuals framed within a contemporary world of work and domesticity. Artist and curator Jeff Thomas’s contribution “Emergence from the Shadow: First Peoples’ Photographic Perspectives” concludes the book’s last section and its colonial narrative with a discussion of the ways in which the “imaginary Indian” can function as a mode of identification for First Nations subjects. Thomas discusses an exhibition that he staged at the Canadian Museum of Civilization pairing historical photographs of Aboriginal subjects with contemporary works by First Nations photographers. His objective was to build a connection between historical and contemporary subjects and forge a sense of historical continuity.

Each section of the book begins with a study of colonial encounters and ends with an alternative to or critical reflection on the representation practices at issue in a distinct historical moment and mode of production. Part 2: Circulating Narratives follows the movement from colonialism to post-colonialism, through the Cold War years and the burgeoning of Canadian nationalism and Quebec separatism, considering the circulation of ideas about Canada produced in mass-mediated photography. Part 3: Remembering and Forgetting reflects on the archival age, focusing, in particular, on artistic practices enlisted to redress official memory.

Although not all contributions in the book address colonialism directly, all speak to related concerns. James Opp’s astute study of aircraft manufacturer Canadair’s advertising campaign against “the threat of Communism” considers the rhetorical limits of photography during the Cold War. Essays by John O’Brian and Blake Fitzpatrick discuss representational issues of political transparency in historical accounts related to the nuclear era. Sarah Stacy traces the rise and fall of the photo-weekly during the 1970s, considering the proto-multicultural discourses of Weekend Magazine as distinct from the nascent nationalism evinced by Perspective, its French-language sister magazine. And though Vincent Lavoie’s essay “The Aesthetics and Ethics of Press Pictures in Canadian Contexts” does not consider political history directly, the standards by which press pictures are judged tell us much about the political landscape of contemporary representational practice. Where and when is a historical event – and who and what historical subjects are – deemed newsworthy? When can and should private life be made public? As all of the contributions to this book attest, these are issues that bear close scrutiny and studied consideration.

The Cultural Work of Photography in Canada is a major achievement. The depth and quality of the scholarship that it presents are impressive and the whole is extremely fascinating. This said, the absence of writing on colonial, post-colonial, and Indigenous photographic practices in Quebec and Eastern Canada is felt and regrettable. Although the editors acknowledge the limited purview of the book, one can only hope that the cultural work of photography in eastern Canada will be considered next time around.

Cheryl Simon is an academic, critic, and curator whose research interests include explorations of time in media arts and collecting and archival practices in contemporary art. She teaches in the MFA-Studio Arts program at Concordia University and in the Cinema + Communications Department of Dawson College, both in Montreal.