[June 20, 2022]

By Michel Hardy-Vallée

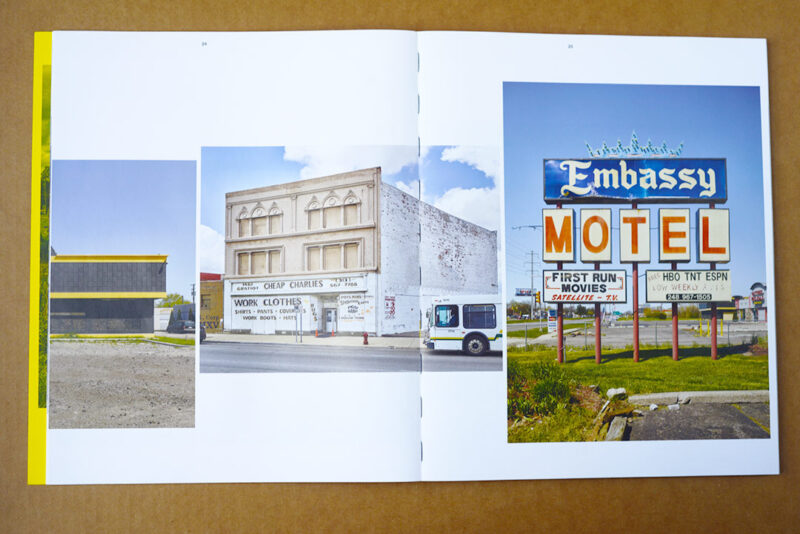

Outside of Detroit, it’s most likely that the symbols of this post-industrial city are its ruins: of houses, large and small; of automobile plants; of grandiose theatres. They epitomize its ruptures, but they teach us nothing about its continuities. Photographers Isaac Diggs and Edward Hillel attempt in this book to outline a more durable Detroit institution than GM: techno music. In the vernacular typology, Detroit is to techno what Chicago is to house and Bristol to trip-hop. The city is foundational to a sometimes dark and introspective synthetic sound that can also rise to shimmering heights of ecstasy and futuristic brilliance. It is one of the backbones of rave culture worldwide.

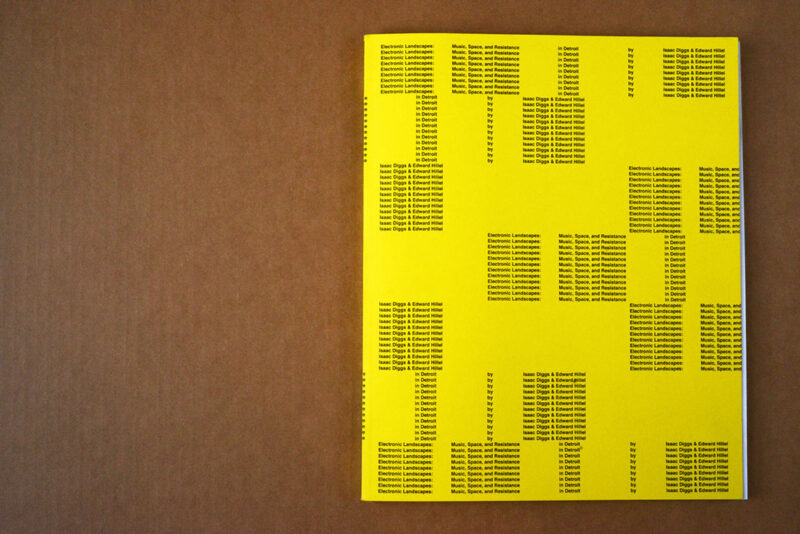

Diggs and Hillel emplace this sound by photographing the buildings, studios, record stores, streets, and public and private spaces where Detroit techno lives. Both have broad-ranging credentials in the visual arts, community work, and education that address the themes of urban experience and memory. Diggs has recently published Lost, LAGOS (2019) and previously collaborated with Hillel on 125th: Time in Harlem (2014). In Quebec, Hillel is perhaps best remembered for his book The Main (1987), a collection of black-and-white photographs and essays about life and immigration on and around Montreal’s Boulevard Saint-Laurent, but his track record also includes projects about Harlem, Berlin, and Valencia. Their combined backgrounds allow them to attend to the multiple layers of meaning materially encoded in the urban fabric and have opened the doors to the creators that make Detroit a techno city.

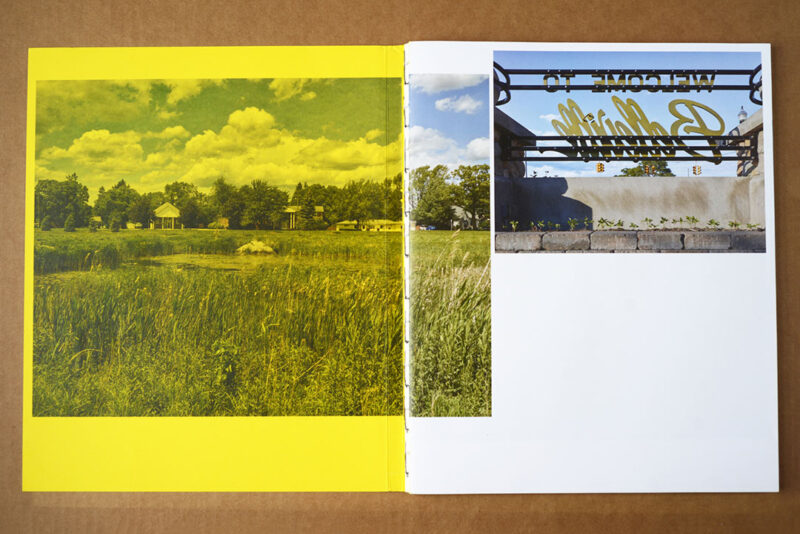

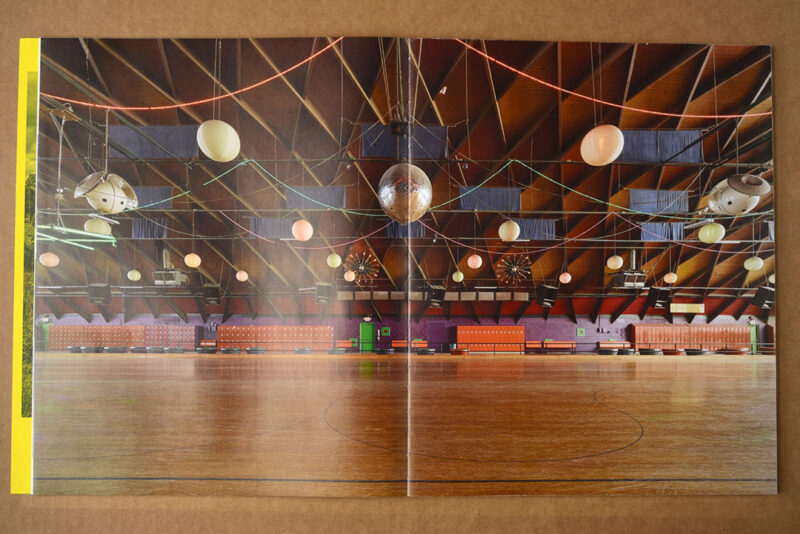

The book begins like an arrival. Fresh out of the airport, we bucket-list a few items: the ruins of the Packard plant, 8 Mile Road, and the Movement Festival downtown. Those are not the focus of the book. The photographs in the opening sequence are packed like an assembly line and laid across the gutter of the book, even wrapping around two sides of a single page, thus virtually creating a leporello within the space of the codex. A full-spread image of the Northland Roller Rink begins the narrative proper and plants the key visual motif of the book: space.

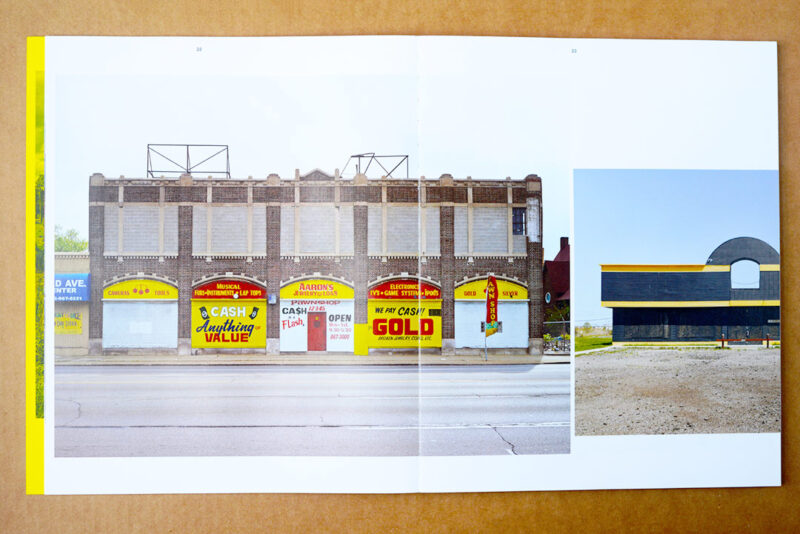

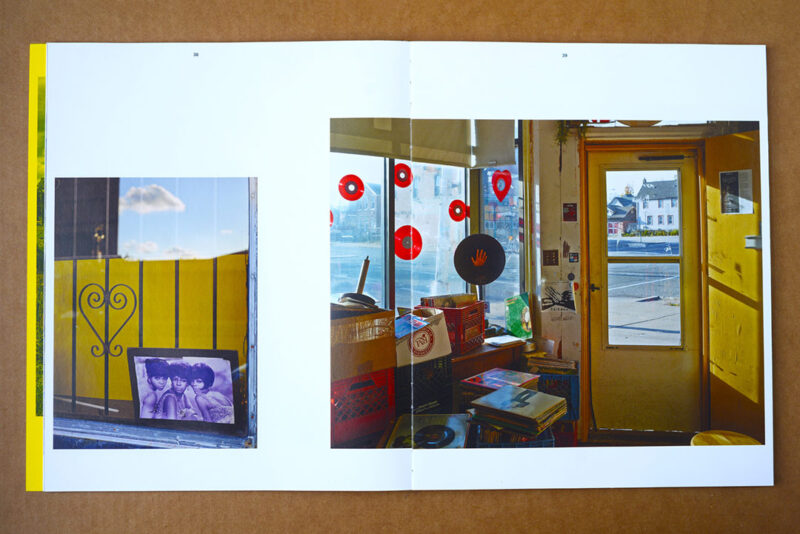

Detroit is a capacious city – enormous buildings, urban sprawl, and empty spaces – and also mainly a Black one. In a racially divided society, predominantly Black spaces are targets for oppression, generating acts of resistance and occupation, such as the development of independent institutions, in response. A faded photo of Diana Ross and the Supremes, superstar group of the golden era of Motown Records, is angled in the window of a record store as a historical landmark of Black-owned cultural industries.

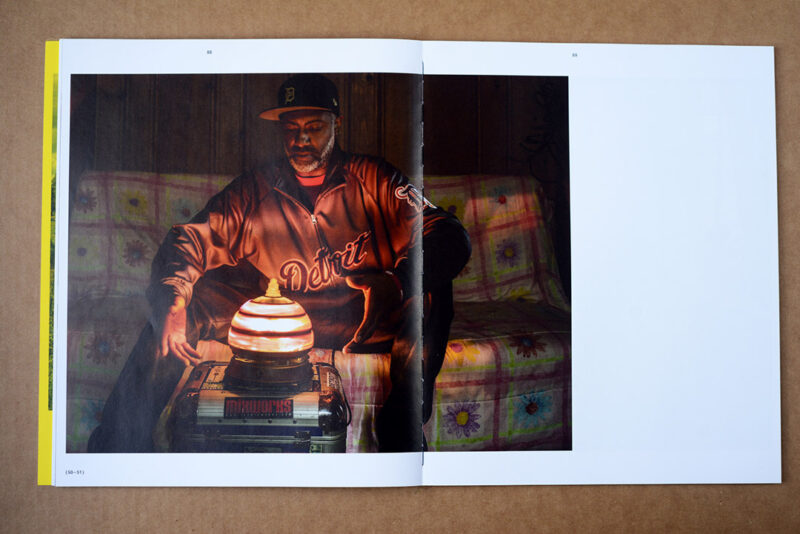

The bulk of the book is a combination of environmental portraits and still lifes sketching out the spaces of techno artists and of related creators and facilitators. In intense colours and complex compositions that sometimes recall William Eggleston or Fred Herzog, Diggs and Hillel portray zones of work in progress. The resulting images suggest a combination of creative chaos and sophisticated formal organization: unlike the ruins that suggest neglect, these images show how the cultural and material fabric of Detroit is cared for and improved. High-tech tools sit cheek by jowl with artefacts that stir memories, akin to how a machine shop might be organized.

As is typical of documentary projects, the book closes with interviews that contribute more sociological and political context to the photographs; less typical are two subsequent “outtakes” sections. All of the pictures from the main part of the book are reprinted at a smaller size and combined with additional ones. The first section is concerned with places and the second one with people. In the technical language of computer databases, this is akin to performing separate queries on multiple tables using two different sets of foreign key constraints. In practice, these sections visually expand the context of each photograph, like an extended cut or a remix – practices that are now essential to the phonographic work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction1. Finally, multiple cross-references pepper the book: numbers in parentheses below photographs point at related pages. Thanks to the design by Wax Studios, the book wears its architecture lightly.

Produced over a six-year span, the book is folded over the before/after of COVID-19 and the murder of George Floyd. It shows the vitality of Black spaces in America and hints at the barbarians at their borders. Contemporary documentary photography tends to favour fragmentation and ellipsis; in this book, we see instead the importance of narrative continuity and multidimensional coherence in exploring a theme.

Michel Hardy-Vallée is a historian of photography and Visiting Scholar at the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art, Concordia University. His research is concerned with the photobook, visual narration, interdisciplinary practices, and the archive, in the con- texts of Quebec and Canada. He has published his work in History of Photography and through a number of edited collections and conference papers. He is currently working on a monograph about Montreal photographer John Max (1936–2011).