In the fall of 2014, the Pompidou Centre inaugurated a new exhibition space devoted to photography. Beyond the strictly local consequences involved, such a decision by a world-class museum may be understood as unequivocal recognition of the legitimacy now granted to this medium within the contemporary art system and canonical institutions. Clément Chéroux, conservator of photography at the Pompidou Centre, explains the reasons in principle for this decision, as well as the theoretical implications inherent to it.

Rémi Coignet : Why did the Pompidou Centre choose to open a gallery devoted to photography?

Clément Chéroux : Three years ago, the president of the Pompidou Centre, Alain Seban, asked me to think about different possibilities for creating a specific space for photography. So, I observed the situation of pluridisciplinary institutions that have photographs in their collections, but also painting, sculpture, and video. I realized that there were generally two models.

The first model, more American, in force at the Metropolitan and MoMA in New York, consists of presenting exhibitions and the collection in a photography gallery and not to have photographs in the rest of the museum. The other model, more European – that of the Pompidou Centre since it opened in 1977 and also that of the Tate today – consists of presenting photography in the permanent collection exhibitions and, from time to time, in major exhibitions. Each model has advantages and disadvantages.

The American model makes it possible to show the collection and the work of the conservators, but it has a shortcoming: it does not allow for a dialogue with the arts. Today, how is it conceivable to have a gallery on surrealism or constructivism without including photographs? The European model presents exactly the opposite advantages and disadvantages. Once we made this observation, we decided to follow both policies at the same time: to continue to have photography in the museum, but also to have a specific space for photography. We will have three exhibitions a year there: one historical, one contemporary, and one thematic.

RC: In fact, after the inaugural exhibition devoted to surrealist photographer Jacques-André Boiffard, the current thematic exhibition, Qu’est-ce que la photographie ?, brings together artists as diverse as Brassaï, Ugo Mulas, and Mishka Henner. Is this question asked about the medium a possible definition of photography as artwork?

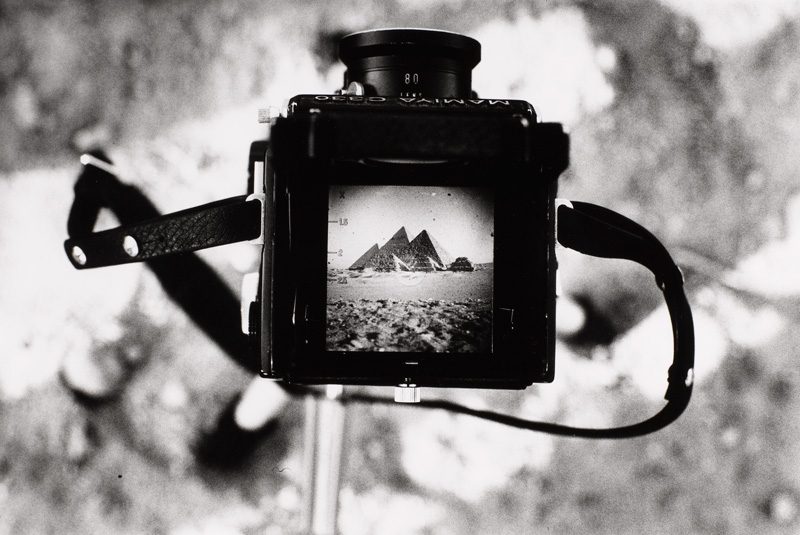

CC: What interested us in this project was to show some thirty artists who, from the 1920s to the present, have asked that question: “What is photography?” And we can evoke, indeed, Man Ray, Ugo Mulas, Jeff Wall, and, more recently, Mishka Henner, who asked themselves this question and answered through a photograph or a series. This question, which we could call ontological, has been asked since the beginnings of photography. But at certain times it has been asked more intensely than at others. As we know, this always happens when there are great upheavals in photographic practices – for example, when photography became industrialized in the mid-nineteenth century; when the transition was made from the collodion wet-plate process to gelatin silver bromide in the late nineteenth century; when, in the 1920 and 1930s, small-format photographs began to appear and to invade the press; when, in the 1970s and 1980s, there was cultural and institutional recognition of photography; and today, with digital photography. It is when practices change that the question is asked.

What is special about this exhibition is that it asks this ontological question not from a theoretical point of view, but in relation to photographic practices, with the idea of leaving it up to the artists to tell us what photography is. The subtext, for us, is to show that one cannot answer this question that is omnipresent in the theoretical discourse, because there is no ontology of photography. There are only individual and specific responses. As we can see, when thirty artists are brought together, each has his or her own response. One will say, “For me, photography is light,” and someone else will say, “For me, it’s memory,” and yet another will say, “It’s the framing, the decisive moment, it’s the gap between reality and representation.” So, it’s a slightly perverse exhibition because we appear to be posing the ontological question “What is photography?” in order to bring an answer, but in fact it’s impossible.

RC: What I wanted to ask you, but you can expand on it, is: What is it for you, as a conservator, that defines a photograph as an artwork?

CC: What makes an artwork? It’s a completely legitimate question, but not necessarily linked to “What is photography?” I would say, today, that what makes an artwork is an approach. It’s someone who gets up in the morning saying, “I’m going to think about a subject and I’m going to propose a visual form that will be intended for a public and that, in the end, will transmit the question that I asked myself.” For me, today, that’s what makes an artwork, as compared to an applied photograph. In the early twentieth century, Aloïs Riegl talked about Kunstwollen, the desire to make art. And that’s exactly it. But photography greatly complexifies the notion of making an artwork, and it complexifies our relationship with art. One of the specificities of photography is that, sometimes, a photograph made without an approach, without a desire for art, may be as powerful and interesting as a photograph made in an art context.

RC: This relates to the work on found photographs . . . CC: That may be the case for amateur photography, reportage, fashion photography, photographs made anonymously, by surveillance cameras, or in a photo booth, for example. In art as it has been constructed since the Renaissance, there has always been an artist with expertise who spent much energy to produce a work of art. What photography has come to teach us is that an anonymous image, or sometimes an image with a creator who didn’t necessarily want to make art, can provoke emotion or questions among those who look at it. This is how photography shook the foundations of art. And Marcel Duchamp and László Moholy-Nagy understood this very well in the 1920s. We realize that a number of artists who used photography in the twentieth century and are the most highly placed on the recognition list – I’m thinking, for example, of Walker Evans, Moholy-Nagy, Diane Arbus – talked constantly about the power of vernacular, amateur, and scientific photographs. Moholy-Nagy was always saying that people should look at scientific photographs; Walker Evans, architectural photographs; Diane Arbus, family albums. These artists incessantly turned toward this other photography. So, today, I think that an institution like the Pompidou Centre, whose mission is to promote artists and artworks, should also look toward this photography – vernacular, amateur, architectural, press – because there are things to learn from them.

RC: Yes, and this intersects with what you said before, that the status of photographs evolves over time.

CC: Sometimes, documentary photographers or amateurs become artists. How could a child like Lartigue, who made his photographs to amuse himself, find his photographs on display at MoMA in the 1960s and become one of the most brilliant photographers of the twentieth century? How did Eugène Atget, who made “simple” documentary views of Paris, come to be perceived today as one of the great photographers of the twentieth century, on display in the finest museums? And so this dimension means that photography is complex, that it is not easily comprehensible according to the usual visual grids that we apply to art. That’s why when we organize a Cartier-Bresson show, we don’t focus only on the surrealist artist Cartier-Bresson of the 1930s. We also show his reportage, his commissions, and how these facets bounce off each other. That’s also why we organize a show like Paparazzi! at the Pompidou Centre-Metz.

RC: In fact, I wanted to talk to you about what could be considered a big disparity: being at the same time curator of the Cartier-Bresson show and the Paparazzi! show. How do you define the position of conservator-curator?

CC: For me it is precisely not a big disparity but, on the contrary, an attempt to reconcile the opposites that are the very nature of photography. Photography is as much about the paparazzi as it is about the artists, and I think that we cannot understand it if we separate these two opposites. I think, on the contrary, that it’s extremely important to show the areas of permeability that are established among these different domains. We have tried to show through Paparazzi! that today many artists look at paparazzi photography and integrate its codes into their own works. We also wanted to point out that it is by reestablishing this dialogue between “non-artistic” photography and artistic photography that we can better understand what photography is. For me, and I’m well aware that this could seem like a big disparity, it’s to be as fair as possible in an attempt to understand this particular medium.

RC: And so, your ambition is to embrace the entire field of the medium, without defining what is art and what isn’t?

CC: What interests me is to allow for this recomplexification of photography. I’ll give you an example. When we hang Picassos in a gallery for a better understanding of cubism, it is useful for us to have a few African masks. And so it’s exactly the same thing with photography. If I really want to show the visual revolution that was the invention of rayography and the photogram by Man Ray and Moholy-Nagy in the early 1920s, we need a few radiographs, a few photographs produced with x-rays, that allow us to understand why these fairly abstract images had an impact on art in the 1920s. It’s simply a question of having a few examples to provide a better understanding of the complexity of photography.

Translated by Käthe Roth

Rémi Coignet is the editor-in-chief of the magazine The Eyes, concerned mainly with Europe and photography. Since 2008, he has written the blog Des livres et des photos on the website of the newspaper Le Monde. In 2014, he published Conversations, a collection of his interviews with photographers such as Lewis Baltz, Anders Petersen, Daido Moriyama, and Pieter Hugo. Conversations is available in English and French editions.