Battat Contemporary, Montreal

December 4, 2014 to February 8, 2015

By James D. Campbell

This captivating exhibition of new work by Kathleen Ritter is aptly and enticingly titled Camoufleurs. A camoufleur was a person – usually an artist, usually a woman – who designed and installed military camouflage in one of the world wars of the last century. The term relates to all First and Second World War specialists in the art of camouflage.

Surrealist artist Roland Penrose once wrote that he and Julian Trevelyan were both “wondering how either of us could be of any use in an occupation so completely foreign to us both as fighting a war, we decided that perhaps our knowledge of painting should find some application in camouflage.” 1 Similarly, Ritter uses art as a sort of potent smokescreen to explore feminist concerns that are still topical and pressing today. With irrepressible wit and considerable savvy, she has created her own Enigma machine to decode secret histories of the early twentieth century.

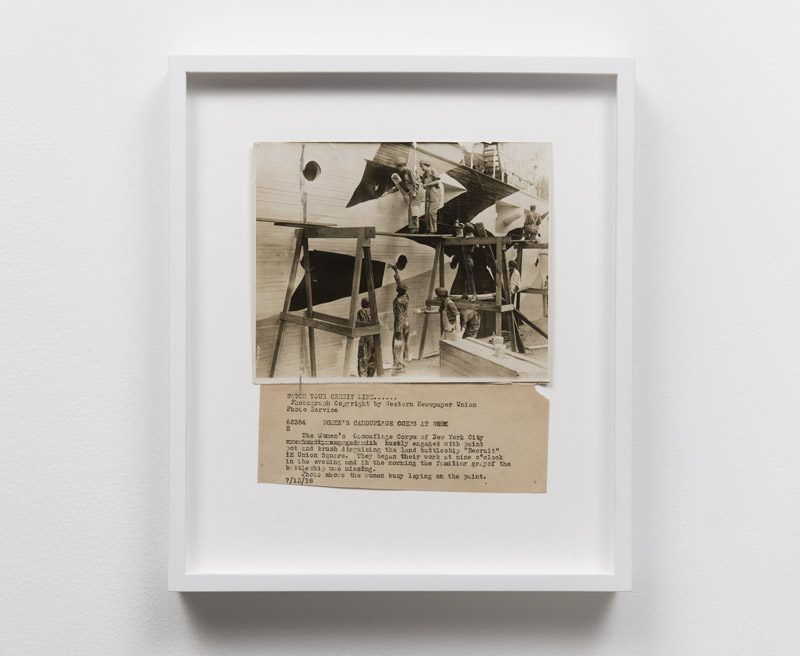

Ritter covered some of the inner walls of the gallery with a huge painted mural in what look like outsize zebra stripes. The dazzling Op Art-like stripes – think Hurtubise unfettered in real space or, better, Bridget Riley’s abstracts – are based on camouflage patterns that cloaked Allied navy ships during the First World War. Ritter’s design is drawn from an archival photograph, discovered in the course of her research, showing members of the Women’s Camouflage Corps covering a landlocked boat (used as a recruiting station in downtown New York City in 1918) with painted dazzle camouflage.

Other notable works in the exhibition include Manifesto (2014), a remarkable transliteration of Mina Loy’s 1914 “Feminist Manifesto” into shorthand – an abbreviated form of writing that was once used by stenographers taking dictation – and printed as an unlimited edition on newsprint. (Larger framed examples appear on an adjacent wall.) The stacks of newsprint on plinths themselves became sculptural objects sans pareil, and viewers were entreated to leave with copies to add to their own collections. This feminist tract was an effective indictment of the Futurists’ self-proclaimed “scorn for women” and still enjoys resonance today. Loy is obviously an avatar of Ritter’s – a maverick author, artist, feminist, and inventor who hobnobbed in Paris in the 1920s with writers such as Djuna Barnes, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound.

A video installation, titled Siren (2014), highlights a scene featuring Hedy Lamarr from the silent 1933 film Extase – in which she seems to be engaged in making erotic hand signals – and successfully dovetails it with the soundtrack from George Antheil’s 1924 avant-garde composition Ballet mécanique. Released with the promotional tagline “the most whispered-about picture in the world,” Extase achieved some notoriety with its consummately erotic depiction of sex. None other than Henry Miller, probably obsessed with scenes of the young Lamarr swimming naked, penned an essay about it. Ritter brilliantly edits the footage without eroding its erotic resonance one iota to relate it to the landmark invention by Antheil and Lamarr of a “Secret Communication System,” widely known today as frequency hopping: the repeated switching of frequencies during radio transmission, in order to undermine “electronic warfare” – the unauthorized interception or jamming of telecommunications systems.

Ritter has shown herself to be an expert camoufleur in disguising and concealing her true intentions behind historical tropes of camouflage and secret coding systems. Using subterfuge, and adroitly mining and quoting from relevant archives, she encourages viewers to decipher her meanings, and to be rewarded and uplifted thereby.

In this exhibition, and its previous exhibition of works by Beth Stuart, Battat has shown a highly distinctive curatorial bent and featured tremendously reparative acts of artistic archaeology and scholarship, bringing a very compelling feminist aesthetic into the foreground of contemporary artistic production.

The writer and curator James D. Campbell writes frequently on photography and painting from his base in Montreal.