Plein sud, Longueuil

February 21 to May 18, 2015

By James D. Campbell

Lefort fittingly cribs his title from American author Herman Melville’s 1851 magnum opus Moby Dick: the Pequod is a fictitious nineteenth-century Nantucket whaling ship that appears in the novel as an instrument of revenge. Narrated by Ishmael (here, Lefort), the story follows the ship’s strange captain, Ahab (perhaps also Lefort), who is still recovering from losing his leg to a rogue sperm whale on his last voyage. His fierce desire to pursue and kill that great white whale, the Moby Dick of the novel’s title, is fuelled by his belief that the creature is the pure embodiment of evil and must be expunged.

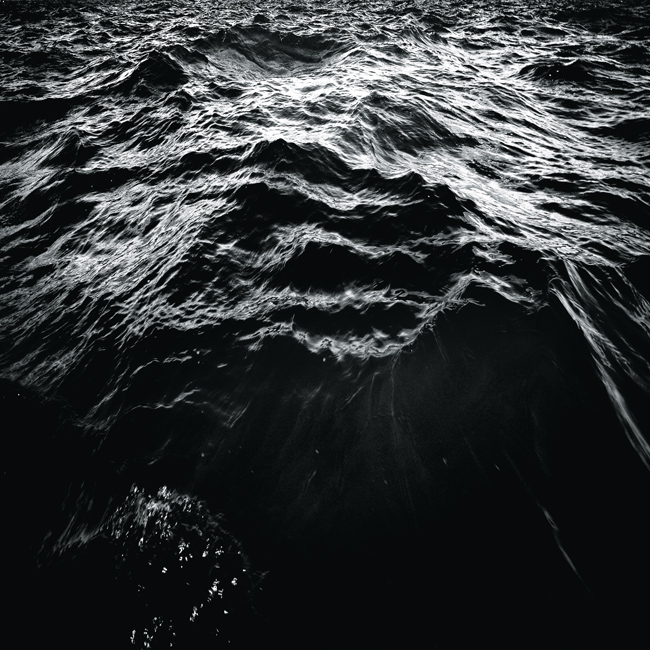

In his Pequod series on exhibit here, Lefort searches not for a paradigm of evil as Ahab did, but for the numinous itself in the compass of a camera lens. This is not surprising, since he has historically been drawn to images of the natural environment with an almost profane joy. Certainly, his images of the bayou and other tropes of nature demonstrate the truth of this. Here, equally powerful, it is the sea…

These images of untamed water convey their ferocity with rare immediacy, and the vulnerability of the photographer equally well. That vulnerability is felt in confrontation with a natural force that is unrelenting, rife with numinosity – and inimical in its mien.

The word “numinous” was coined by the Lutheran theologian Rudolf Otto and discussed at length in his highly influential book The Idea of the Holy (1923).1 According to Otto, the numinous experience installs the tremendum that brings on fear and trembling, a quality of unfettered fascinans, the tendency to attract, fascinate, compel – and terrorize.

Somewhere between brutality and sophistication, Lefort shows the personal quality integral to the numinous experience, a feeling of being somehow in communion with something altogether outside himself, something replete with alienness, outside the circles of time, savage and unnameable. He succeeds in evoking the mysterium tremendum – the once and wholly Other – in his images of an unforgiving sea, and his own fragility in the face of it. The sea itself is the inimical Great White Whale, and the Pequod pursues it like a transcendent mystery across a radius drawn by the artist himself in space, time – and textures of light.

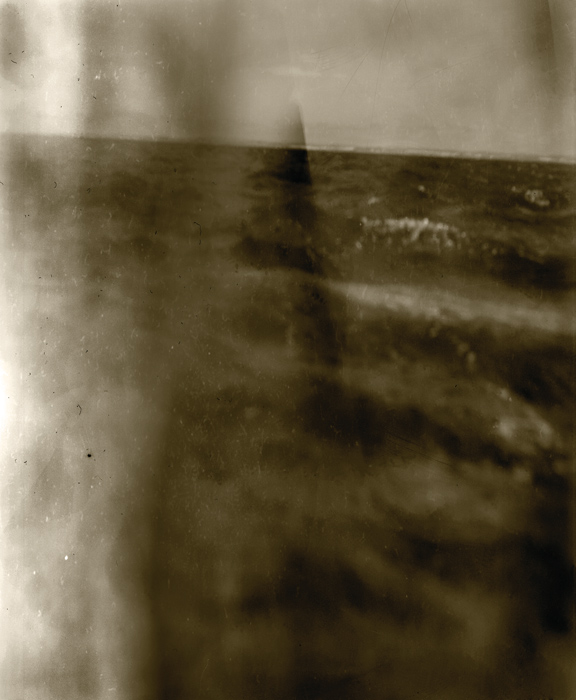

Lefort’s images seem to have been shot at the helm of a wave-drenched binnacle, with compass and octant close at hand, and all is in a state of irredeemable flux, as the ship pitches and rolls on the face of the deep and fateful cusp of jeopardy that is the open sea. The fact that he is in a kayak and not at the helm of a large sailing ship is not immediately apparent. There seems to be a porthole – a window, as the late, great photographer Charles Gagnon would say, between inside and outside, and, more importantly, between shifting epistemologies of seeing and seen. Serendipitous light leakage in the bellows of his 4 x 5 camera yielded a ghostlike shape at the left side of the images, which seems related to an arm thrown up defiantly against the hegemony of the sea and the nameless perils of the deep.

He conjures out of raw experiences of being “at sea” a curious collision of the Romantic sublime and its Gothic counterpoint: Romantic because his quest for the numinous is heroic and enduring; Gothic because the observing self is obviously in jeopardy and subject to surreal visions and fractured perspectives. A palpable sense of threat and imminent collapse (capsizing) and vertigo hangs over all. To hold these very different species of the sublime in balanced counterpoint is no easy task. Yet Lefort makes it seem effortless – a bravura high-wire act second to none.

Here is a photographer bravely and even obsessively in pursuit of his own enigma, his very own Great White Whale; I mean, the numinous truth of the photographic image itself, and all that it conceals, implies, and portends.

The writer and curator James D. Campbell writes frequently on photography and painting from his base in Montreal.

[See the printed or digital version of the magazine for the complete article.]