AxeNéo7, Gatineau

April 1 to May 2, 2015

By Judith Parker

The artist’s body as a site for the investigation of the internal dualities of the self is the subject of a compelling exhibition of video projections, kinetic sculptures, and drawings by Montreal artist Manon Labrecque. As she was trained in contemporary dance and visual art, many of Labrecque’s recent works engage the gesture of touch – the energy and physical contact between the hand and the body – to communicate a deeply sensed corporal and psychic experience of being.

Curated by Nicole Gingras, the exhibition occupies three spaces, each with its own distinct mood, media, and spatial presence. First, I stepped into a gallery infused with abundant natural light in which six oversized drawings (1.3 metres x 1 metre) on heavy paper, Les uns (2008–15), were displayed on slim easels arranged in the centre. Two drawings greeted the viewer; their primal human figures were sensitively rendered in the manner of an untutored child – but in fact were drawn by the artist with her eyes closed, relying on memory.1 They conveyed a lively spiritual presence – a subconscious depiction of the self or, in this case, selves. For in each of the sinuously delineated graphite drawings there are two semi-merged or semi-joined female figures, suggestive of psychic companions or the inner duality of being. One drawing is reminiscent of twins conjoined at the head and hip. In all of them, the unclothed bodies have exaggerated and enlarged limbs, hands, fingers, feet and toes, creating a sort of haptic map that traces the sensation of touch, feeling, and memory of the body itself. Fingerprints, handprints, smudges, and other direct hand marks in a vibrant range of oil-pastel colours, probably made with eyes open, accentuate and narrate these bodies. The marks include ovals above the head suggestive of coronas of light, inner female organs, and smiling lips that generate fields of positive psychic energy.

However, there is also a sense of unease and the uncanny in the dissolution or non-resolution of body parts in relation to the whole. In one horizontal drawing, a set of “twins” engage in a fight – bodies separate and fall, arms flail, and mouths grimace – it’s a primal battle of the selves. Interestingly, Labrecque’s title, Les uns, part of the expression les uns et les autres, meaning “one another” or “each other,” alludes to the forever intertwined and inseparable parts of the self.

Following this introduction to Labrecque’s artistic vocabulary, I entered a room with video installations. Touchée (Affected, Touched; 2015, 4 min. 50 sec.), comprises a small, intimate video screen suspended in space, visible from both sides, with a drawing of two hands on one surface. A slightly unfocused black-and-white video shows a woman in a plain dark dress (the artist), her eyes closed, her arms and hands outstretched, slowly moving and seeking with hand gestures a sketch of her hands in magenta ink – clearly visible in front of the viewer. Sensing her way, the woman eventually discerns the correct alignment of her hands on top of the drawn ones. How does she do this? Evidently, the artist has tapped into the capabilities of her haptic, sensing body.

A large video projection, Apprentissage (Apprenticeship; 2015, 5 min. 56 sec.), presents two overlapping and aligned representations of a mute woman. One, a magenta outline drawn directly on the wall, remains upright and static, while the other, a very blurred black-and-white video image of the same woman, a ghostly “memory woman,” moves; she holds and feels her head and torso, then crouches and lies down in slow motion. The two bodies become misaligned but nevertheless remain joined at the feet. The now-motionless horizontal figure is suggestive of death, and the question of two selves also becomes one of body-memory connections that have inter-generational implications.

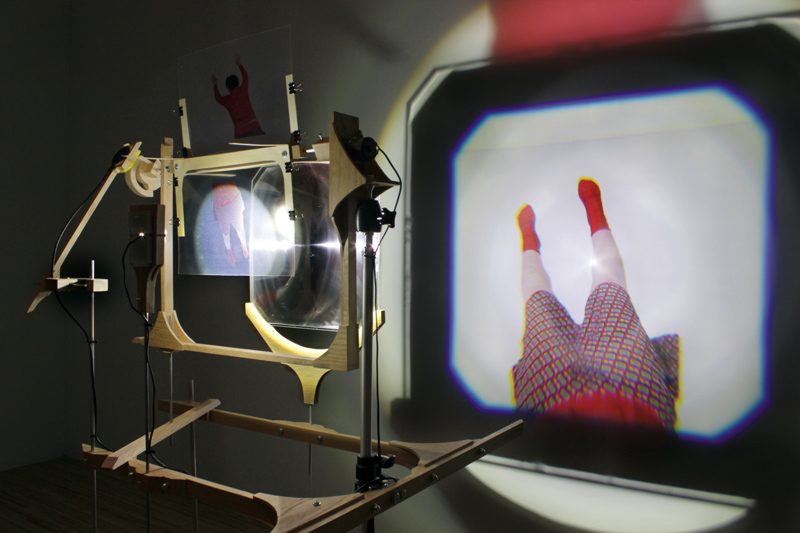

The third room presents three kinetic sculptural installations that lie still, dark, silent, and in waiting, ready to surprise the viewer who triggers their audio and visual sequences on entering the space. It’s a bit like entering a carnival funhouse: the cacophonous overlapping, amplified mechanical sounds and rhythms are insistent, playful, and nonsensical; moreover, the room is sporadically illuminated by rotating transparencies depicting fragments of a woman dressed in red, enlarged and projected on the walls. The works’ title, Moulin à prières (Prayer Wheel; 2015), references Buddhist prayer wheels rotating on spindles, the same motion as the revolving still images of the artist. In one work, she covers her face with her hands; in the second, three rotating images show hands gesturing – clenched, open, and extended as if giving or receiving; and in the third, two images separate the upper and lower body; they all swing rapidly into view and then recede as if flying through the air into darkness. The overall effect is ironic; what do all the mechanical gestures and rituals amount to? They appear empty of genuine spiritual meaning and speak more of alienation and dislocation, while nevertheless maintaining an honest individual human presence.

Judith Parker is an Ottawa-based curator and art historian. Recently, she completed a residency at Elsewhere Living Museum in North Carolina and co-curated Beyond the Edge: Artist’s Gardens 2014 at the Experimental Farm, Ottawa.